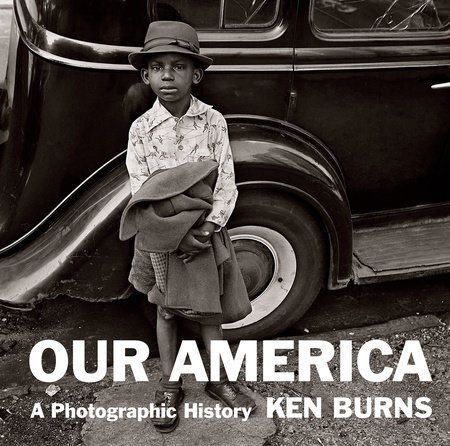

A Powerful Monument to Our Moment

One might argue that the best-known and most compelling group of photographs made in (and of) the United States was published by the Museum of Modern Art in 1938. It was called, simply, American Photographs, and it included eighty-seven photographs by Walker Evans made between 1929 and 1937. Someday, the volume you hold in your hands might assume comparable status, but that is for future generations to determine. Soon—in this essay, even—we will consider a number of titles that compete for this distinction. Specific rankings are surely beside the point, yet American Photographs is undoubtedly foundational in constructing a picture of America within our popular imagination. In his essay that accompanied Evans’s photographs in the bound volume in 1938, the critic, collector, and influencer Lincoln Kirstein wrote,

After looking at these pictures with all their clear, hideous and beautiful detail, their open insanity and pitiful grandeur, compare this vision of a continent as it is, not as it might be or as it was, with any other coherent vision that we have had since the war. What poet has said as much? What painter has shown as much? Only newspapers, the writers of popular music, the technicians of advertising and radio have in their blind energy accidentally, fortuitously, evoked for future historians such a powerful monument to our moment.

Kirstein wrote this at a time when the status of photography among the fine arts was hardly secure. His favorable comparisons with poetry and painting carry with them a hint of this insecurity: his contemporary audience was inclined to look to the written word or the painted image as a model for a “coherent vision.” Kirstein then pivoted to an astute, if less conventional, claim, pointing to other popular forms (journalism, advertising) as comparably noteworthy and historically significant. After positioning American Photographs between these “high” and “low” achievements, Kirstein concluded, “Evans’ work has, in addition, intention, logic, continuity, climax, sense and perfection.” It is difficult to imagine higher praise.

Kirstein and Evans shared a confidence that photography, the most democratic of media, was well suited to construct a picture of America. Even a passing familiarity with Ken Burns’s documentary films would lead one to conclude that he agrees with this assessment. They believed not only that a group of photographs, thoughtfully chosen and sequenced, could do this more effectively than a haphazard assortment, but also that the group as a whole could transcend its component parts and become even more powerful as an indivisible statement. One might say American Photographs proved that potential. Our America is a variation on this concept, reinforcing the principle while differing in a few notable ways. Each book offers the story of a nation told through photographs. Each is guided by a singular sensibility, authored by an individual with an attentiveness to (and an affection for) the particular pleasures of the medium. Some obvious distinctions scarcely need mention: all of the photographs in American Photographs were made by Walker Evans, within an eight-year period. The photographs in Our America were made by scores of individuals, both known and nameless, over nearly two centuries.

Photography has always been in the hands of many. It was not a practice learned in an academy that discouraged (or forbade) the full participation of women. Technical and financial barriers to entry were relatively low, and decreased as the nineteenth century progressed. From its infancy, photography served many different functions for many different people: scientists used it to capture significant detail and facilitate comparison, photojournalists deployed it to expand or complicate the public’s understanding of newsworthy events, artists wrangled with its mechanical limits in pursuit of aesthetic pleasures, and perhaps most importantly, people everywhere (sometimes with the help of entrepreneurial professionals) used it to capture likenesses of their loved ones and details of their lives. Evans appreciated this breadth and adopted the plainspoken visual language of functional photographs for much of his career, although the fact that American Photographs was published by MoMA points to the core audience for these works: those interested in art, and specifically in art made with a camera. Evans’s signature style may have evoked the unassuming charm of photographs made at a local commercial studio, but his concerns were anything but pedestrian. Generations of art historians (including Kirstein), often in dialogue with Evans, have sought to define the nuances of his ambition: that elusiveness is at the heart of what distinguishes his achievement from the one in your hands. The first-person plural implied by the title of Our America is meant to include anyone interested in photographs of America, a plurality that also extends to the multiplicity of purposes for which these photographs originally were made. In this it differs from most other books of photographs that concern themselves with a similar topic, both before 1938 and since.

•••

One of the most radical, and enduring, aspects of Evans’s achievement was that a photograph didn’t have to emulate other media to merit serious artistic attention. Photographers with artistic ambition in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (often referred to as “pictorialists”) often adopted soft-focus, dramatic perspectives, and painstaking processes to align themselves, visually, with printmaking or drawing. They saw this as necessary to distinguish their achievements from hordes of professionals and amateurs who were churning out thousands upon thousands of photographs every day. Examples of what the pictorialists found so threatening abound in Our America: images filled with previously unimaginable detail (some fascinating, some horrifying, some both); scenes of gatherings and events that provided a sense of being there beyond a standard written report; photographs of friends and family intended for the album page or home display. Evans approached his subjects directly, with an unembellished, functional aesthetic that harkened back to these humble cornerstones of photographic history, even while he focused his attention on bringing these images into the more rarefied atmosphere of the art world. Our America is similarly positioned to connect the wildly disparate corners of the photographic medium, with the notable distinction that these images were rarely considered in artistic contexts. Evans adopted photography’s plainspoken local dialect—often referred to as its “vernacular traditions”—but the goal was to give them due consideration as Art.

The vast majority of the photographs that appear in Our America, while attentive to aesthetic considerations, weren’t made for museums. Even considering the first few images reproduced on these pages one grasps the ways in which the photographic medium echoes the democratic pluralism of the country in which they were made. The earliest image here was made in 1839, the same year Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre announced his discovery for fixing photographic images to astounded audiences in Paris. It didn’t take long for news to cross the Atlantic, where legions of curious individuals attempted to make their own “mirror with a memory” (as these daguerreotypes, made on highly polished, specially sensitized copper plates were described). Robert Cornelius was working for his family business when he took what is believed to be the first photographic self-portrait in the United States: the result is decidedly more of an experiment than an exercise in narcissism. Cornelius’s wary gaze reveals a skepticism regarding the process (was it really technologically possible to capture one’s own likeness?), not the carefully cultivated OOTD look we have come to expect in the era of camera phone selfies. The sense of curiosity and wonder has evolved with each technological advance: as Garry Winogrand later quipped, “I photograph to find out what something will look like photographed.”

The same daguerreotype process, with a few improvements that shortened the time needed to capture an image, deserves credit for the specificity in the plates that follow. But these are no longer novel experiments: they are deploying photography’s capacity for record keeping in service of goals we can only now surmise. We hope the photograph of Isaac Jefferson can be understood as a declaration of personhood after decades of enslavement. We hope the branded hand of an abolitionist helped inspire others to the cause. Daguerreotypes were unique original images (unlike technologies that easily facilitated multiple prints from a single matrix). The octagonal brass windows reproduced here secured them within a handheld case, so while they may have been passed along, their immediate audience would have been a small one. To circulate more widely they would have been translated into an ink-on-paper reproduction (such as a lithograph or engraving). The image of the U.S. Capitol on the following spread was surely reproduced through these methods to reach as broad an audience as possible, whether as a souvenir or in the illustrated press.

Almost since its invention, photography has served the dual interests of the personal and the popular. Decades before Kodak introduced its No. 1 camera in 1888 (its memorable advertising slogan, “You Push the Button, We Do the Rest,” pointed to the fact that untrained amateurs could capture their own lives on film), Americans were keen to collect family portraits. Whether made by an itinerant photographer or in a local commercial studio, these were available for a fraction of the cost and at a fraction of the time than it would have taken to have commissioned a painted portrait. Our visual record of the populace across the continent began to align with the actual population. The delicate details of clothing and expression and the tender connections conveyed through gesture and pose give us a window into the lives of Iowa tribe members in Missouri as well as a nursemaid and her charge in Louisiana. Once seen, these people and these relationships cannot be forgotten, nor their concerns overlooked. For generations these specific photographs were likely held by those pictured in them, or their descendants, but their presence here is a symbolic representation of tens of thousands of others.

The next image is the first in this volume that might be characterized as newsworthy, a proto-photojournalist’s record of a momentous gathering. As with many news photographs, the caption assumes a particular significance, allowing us to identify that it is Frederick Douglass seated just left of the table. This raises an important feature of this book and the audience it serves: the contrast with Walker Evans’s American Photographs is telling. Each of Evans’s photographs appears on the right side of its own spread with no text other than an unobtrusive sequential number on the opposite page. These numbers allow an attentive reader, at the back of each of the book’s two parts, to associate a brief title (often just a place name) and date with a particular image. Evans’s audience is thus asked to grapple with the evidence of the images themselves, and the sequence in which they appear, long before the minimal contextual information is offered. The text that appears alongside the images in this volume is akin to Evans’s terse titles—only a location and a date—yet even these bare details serve to guide the reader. That they are complemented by extensively researched fuller captions at the back of the book is a generous gesture to those of us who would prefer to enjoy these photographs without requiring the internet to learn more of the context of their creation. This is a book for the curious: an interest in photography’s artistic traditions is welcome, but not necessary.

•••

Our America and American Photographs are arguably the youngest and the oldest of the epic photographic portraits of America, but they are hardly the only ones. After American Photographs in 1938, the photo book came to assume a singular significance within photography’s rich traditions, but also a central role in how we picture ourselves. Only a year later, the photographer Dorothea Lange and her husband, the agricultural economist Paul Taylor, collaborated on An American Exodus, subtitled, pointedly, A Record of Human Erosion. Here a cacophony of voices, often transcribed from interviews with the individuals photographed, are deployed to expand and complicate our understanding of what we see. Evans’s dispassionate approach to a similar moment in our history seems clinical in comparison. Although other marvelous photo books appeared in the ensuing decades, the ambition and impact of these two publications was (again, arguably) not matched until Robert Frank released The Americans to an unsuspecting audience in 1959. In eighty-three images, placed one to a spread (nodding to Evans), the Swiss-born Frank deflated the myth of American prosperity in the middle of the twentieth century and pointed to a much more complex and racially charged nation—an image in which some Americans refused to see themselves (see page 208). It was not simply the subject matter but also the seemingly offhanded way in which Frank deployed his camera that created such a stir. With rough grain and informal, often asymmetric framing, Frank asserted a cool indifference to the precise focus and delicate tonal range then associated with serious photographic efforts. One of the curious things about photographs is the way even the most incendiary ones, in time, can assume new meaning or be deployed in new ways. Frank’s image of a segregated trolley in New Orleans assumes a historical air on these pages, a regrettable fact. When it appeared on the cover of The Americans, the Supreme Court had only recently banned segregation on public transportation and it would be five years before the Civil Rights Act would further assert protection of these rights. The offhanded style of the photographs themselves was similarly normalized as it was adopted by subsequent generations prowling busy sidewalks with a camera.

By the mid-1970s, artists such as Robert Adams and Lee Friedlander were proving and reinforcing the vitality of photo books made in and of the United States with continued creativity and increasing frequency. Color had been expensive, often fugitive (think faded family snapshots), and regularly derided as antithetical to serious artistic intent, at least until about this moment. Photographers such as William Eggleston, Stephen Shore, Janet Delaney, Richard Misrach, Tina Barney, and Joel Sternfeld persuasively demonstrated that cameras containing color film held equal potential as art. As the audiences for these books and the number of publishers increased, opportunities began to emerge for explorations of smaller corners of the American landscape: from Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe’s Daufuskie Island (1982) to Sam Contis’s Deep Springs (2017). For individual artists, the impulse to capture this vast continent with a camera may have waned, but it has been more than counterbalanced by an attentiveness to its constituent parts.

The need to reflect on our history through photography is one that seems ever more urgent. We are consistently reminded that neither history nor photography is ever neutral, and the strength of the photo books discussed here, including this one, is that they acknowledge the priorities of a particular individual. The best stories are those told through a distinctive lens, and that acknowledge the ways in which that lens is shaped by a personal history. On these pages, photographs from the Civil War outnumber images from the past three decades: this selection is guided by a visual historian, not an inventory that draws equally from each year in our nation’s history. While there are a handful of well-known or widely reproduced images here, most will be unfamiliar, and their presence points to the research that we share a responsibility to do, and the stories that remain to be told. Our America is an intentionally idiosyncratic, deeply personal collection of photographs that have shaped our understanding of ourselves and our history. It is, too, a powerful monument to our moment.

—Sarah Hermanson Meister

Copyright © 2022 by Ken Burns. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.