The Long Fall of Flight One-Eleven Heavy

It was summer; it was winter. The village disappeared behind skeins of fog. Fishermen came and went in boats named Reverence, Granite Prince, Souwester. The ocean, which was green and wild, carried the vessels out past Jackrock Bank toward Pearl Island and the open sea. In the village, on the shelf of rock, stood a lighthouse, whitewashed and octagonal with a red turret. Its green light beamed over the green sea, and sometimes, in the thickest fog or heaviest storm, that was all the fishermen had of land, this green eye dimly flashing in the night, all they had of home and how to get there—that was the question. There were nights when that was the only question.

This northerly village, this place here of sixty people, the houses and fences and clotheslines, was set among solid rocks breaching from the earth. It was as if a pod of whales had surfaced just as the ocean turned to land and then a village was built on their granite backs. By the weathered fishing shacks were rusted anchors like claws and broken traps and hills of coiled line. Come spring, wildflowers appeared by the clapboard church. The priest said mass. A woman drew back a curtain. A man hanged himself by the bridge. Travelers passing through agreed it was the prettiest earthly spot, snapping pictures as if gripped by palsy, nearly slipping off the rocks into the frigid waves.

Late summer, a man and woman were making love under the eaves of a garishly painted house that looked out on the lighthouse—green light flashing—when a feeling suddenly passed into them, a feeling unrelated to their lovemaking, in direct physical opposition to it: an electrical charge so strong they could taste it, feel it, the hair standing up on their arms, just as it does before lightning strikes. And the fishermen felt it, too, as they went to sea and returned, long ago resigned to the fact that you can do nothing to stop the ocean or the sky from what it will do. Now they, too, felt the shove and lock of some invisible metallic bit in their mouths. The feeling of being surrounded by towering waves.

Yes, something terrible was moving this way. There was a low ceiling of clouds, an intense, creeping darkness, that electrical taste. By the lighthouse, if you had been standing beneath the flashing green light on that early-September night, in that plague of clouds, you would have heard the horrible grinding sound of some wounded winged creature, listened to it trail out to sea as it came screeching down from the heavens, down through molecule and current, until everything went silent.

That is, the waves still crashed up against the granite rock, the lighthouse groaned, a cat yowled somewhere near the church, but beyond, out at sea, there was silence. Seconds passed, disintegrating time . . . and then, suddenly, an explosion of seismic strength rocked the houses of Peggy’s Cove. One fisherman thought it was a bomb; another was certain the End had arrived. The lovers clasped tightly—their bodies turning as frigid as the ocean.

That’s how it began.

It began before that, too, in other cities of the world, with plans hatched at dinner tables or during long-distance calls, plans for time together and saving the world, for corralling AIDS and feeding the famine-stricken and family reunions. What these people held in common at first—these diplomats and scientists and students, these spouses and parents and children—was an elemental feeling, that buzz of excitement derived from holding a ticket to some foreign place. And what distinguished that ticket from billions of other tickets was the simple designation of a number: SR111. New York to Geneva, following the Atlantic coast up along Nova Scotia, then out over Greenland and Iceland and En- gland, and then down finally into Switzerland, on the best airline in the world. Seven hours if the tailwinds were brisk. There in time for breakfast on the lake.

In one row would be a family with two grown kids, a computer-genius son and an attorney daughter, setting out on their hiking holiday to the Bernese Oberland. In another would be a woman whose boyfriend was planning to propose to her when she arrived in Geneva. Sitting here would be a world-famous scientist, with his world-famous scientist wife. And there would be the boxer’s son, a man who had grown to look like his legendary father, the same thick brow and hard chin, the same mournful eyes, on a business trip to promote his father’s tomato sauce.

Like lovers who haven’t yet met or one-day neighbors living now in different countries, tracing their route to one another, each of them moved toward the others without knowing it, in these cities and towns, grasping airline tickets. Some, like the Swiss tennis pro, would miss the flight, and others, without tickets, would be bumped from other flights onto this one at the last minute, feeling lucky to have made it, feeling chosen.

In the hours before the flight, a young blond woman with blue, almost Persian eyes said goodbye to her boyfriend in the streets of Manhattan and slipped into a cab. A fifty-six-year-old man had just paid a surprise visit to see his brother’s boat, a refurbished sloop, on the Sound, just as his two brothers and his elderly mother came in from a glorious day on the water, all that glitter and wind, and now he was headed back to Africa, to the parched veldts and skeletal victims, to the disease and hunger, back to all this worrying for the world.

Somewhere else, a man packed—his passport, his socks—then went to the refrigerator to pour himself a glass of milk. His three kids roughhoused in the other room. His wife complained that she didn’t want him to fly, didn’t want him to leave on this business trip. On the refrigerator was a postcard, once sent by friends, of a faraway fishing village—the houses and fences and clotheslines, the ocean and the lighthouse and the green light flashing. He had looked at that postcard every day since it had been taped there. A beautiful spot. Something about it. Could a place like that really exist?

All of these people, it was as if they were all turning to gold, all marked with an invisible X on their foreheads, as of course we are, too, the place and time yet to be determined. Yes, we are burning down; time is disintegrating. There were 229 people who owned cars and houses, slept in beds, had bought clothes and gifts for this trip, some with price tags still on them—and then they were gone.

Do you remember the last time you felt the wind? Or touched your lips to the head of your child? Can you remember the words she said as she last went, a ticket in hand?

Every two minutes an airliner moves up the Atlantic coast, tracing ribboned contrails, moving through kingdoms in the air demarcated by boundaries, what are called corridors and highways by the people who control the sky. In these corridors travel all the planes of the world, jetliners pushing the speed of sound at the highest altitudes, prop planes puttering at the lowest, and a phylum in between of Cessnas and commuters and corporate jets—all of them passing over the crooked-armed peninsulas and jagged coastlines and, somewhere, too, this northern village as it appears and disappears behind skeins of fog.

The pilot—a thin-faced, handsome Swiss man with penetrating brown eyes and a thick mustache—was known among his colleagues as a consummate pilot. He’d recently completed a promotional video for his airline. In it, he—the energetic man named Urs—kisses his beautiful wife goodbye at their home before driving off, then he is standing on the tarmac, smiling, gazing up at his plane, and then in the cockpit, in full command, flipping toggles, running checks, in command, toggles, lights, check, command.

So now here they were, in their corridor, talking, Urs and his copilot, Stephan. About their kids; both had three. About the evening’s onboard dinner. It was an hour into the flight, the plane soaring on autopilot, the engine a quiet drone beneath the noise in the main cabin, the last lights of New England shimmering out the west side of the aircraft, and suddenly there was a tickling smell, rising from somewhere into the cockpit, an ominous wreathing of—really, how could it be?—smoke. Toggles, lights, check, but the smoke kept coming. The pilot ran through his emergency checklists, switching various electrical systems on and off to isolate the problem. But the smoke kept coming. He was breathing rapidly, and the copilot, who wasn’t, said, We have a problem.

Back in the cabin, the passengers were sipping wine and soda, penning postcards at thirty-three thousand feet. In first class, some donned airline slippers and supped on hors d’oeuvres while gambling on the computer screens in front of them. Slots, blackjack, keno. Others reclined and felt the air move beneath them—a Saudi prince, the world-famous scientist, the UN field director, the boxer’s son, the woman with Persian eyes—an awesome feeling of power, here among the stars, plowing for Europe, halfway between the polar cap and the moon, gambling and guzzling and gourmandizing, oblivious as even now, the pilot was on the radio, using the secret language of the sky to declare an emergency:

Pan, pan, pan, said Urs. We have smoke in the cockpit, request deviate, immediate return to a convenient place. I guess Boston. (Toggles, lights, check, breathe.)

Would you prefer to go in to Halifax? said air traffic control, a calm voice from a northern place called Moncton, a man watching a green hexagon crawl across a large round screen, this very flight moving across the screen, a single clean green light.

Affirmative for one-eleven heavy, said the pilot. We have the oxygen mask on. Go ahead with the weather—

Could I have the number of souls on board . . . for emergency services? chimed in Halifax control.

Roger, said the pilot, but then he never answered the question, working frantically down his checklist, circling back over the ocean to release tons of fuel to lighten the craft for an emergency landing, the plane dropping to nineteen thousand feet, then twelve thousand, and ten thousand. An alarm sounded, the autopilot shut down. Lights fritzed on and off in both the cockpit and the cabin, flight attendants rushed through the aisles, one of the three engines quit in what was now becoming a huge electrical meltdown.

Urs radioed something in German, emergency checklist air conditioning smoke. Then in English, Sorry . . . Maintaining at ten thousand feet, his voice urgent, the words blurring. The smoke was thick, the heat increasing, the checklists, the bloody checklists . . . leading nowhere, leading—We are declaring emergency now at, ah, time, ah, zero-one-two-four . . . We have to land immediate—

The instrument panel—bright digital displays—went black. Both pilot and copilot were now breathing frantically.

Then nothing.

Radio contact ceased. Temperatures in the cockpit were rising precipitously; aluminum fixtures began to melt. It’s possible that one of the pilots, or both, simply caught fire. At air traffic control in Moncton, the green hexagon flickered off the screen. There was silence. One controller began trembling, another wept.

It was falling.

Six minutes later, SR111 plunged into the dark sea.

The medical examiner woke to a ringing phone, the worst way to wake. Ten-something on the clock, or was it eleven? The phone ringing, in the house where he lived alone, or rather with his two retrievers, but alone, too, without wife or woman. He lived near the village with the lighthouse, had moved here less than three years ago from out west, had spent much of his life rolling around, weird things following him, demons and disasters. Had a train wreck once, in Great Britain, early in his career, a Sunday night, university students coming back to London after a weekend at home. Train left the tracks at speed. He’d never seen anything like that in his life—sixty dead, decapitations, severed arms and legs. These kids, hours before whole and happy, now disassembled. Time disintegrating in the small fires of the wreckage. After the second night, while everyone kept their stiff upper lips, he sobbed uncontrollably. He scared himself—not so much because he was sobbing, but because he couldn’t stop.

There’d been a tornado in Edmonton—twenty-three dead. And then another train wreck in western Canada, in the hinterlands fifty miles east of Jasper. Twenty-five dead in a ravine. He’d nearly been drummed out of the job for his handling of that one. The media swarmed to photograph mangled bodies, and the medical examiner, heady from all the attention and a bit offended by it, knowing he shouldn’t, stuffed some towels and linens on a litter, draped them with a sheet, and rolled the whole thing out for the cameras. Your dead body, gentlemen.

Later, when they found out—oh, they hated him for that. Called for his head.

This had been a frustrating day, though, driving up to New Glasgow, waiting to take the stand to testify in the case of a teenage killer, waiting, waiting, four, five, six hours, time passing, nothing to do in that town except pitter here and there, waiting. Got off the stand around six, home by nine, deeply annoyed, too late to cook, got into the frozen food, then to bed, reading the paper, drifting, reading, drifting. And now the phone was ringing, a woman from the office: A jet was down. Without thinking, he said, It’s a mistake. Call me back if anything comes of it. Set the phone in its cradle, and a minute later it rang again.

There’s a problem here, she said.

I’ll get on my way, he said, and hung up. He automatically put a suitcase on the bed, an overnight bag, and then it dawned on him: There’d been no talk about numbers yet, the possible dead. There could be hundreds, he knew that, yes, he did know that now, didn’t he? He walked back and forth between his cupboard and his bed, flustered, disbelieving, maybe hundreds, and then the adrenaline released, with hypodermic efficiency. Hundreds of bodies—and each one of them would touch his hands. And he would have to touch them, identify them, confer what remained of them to some resting place. He would have to bear witness to the horrible thing up close, what it did up close, examine it, notate, dissect, and, all the while, feel what it did, feel it in each jagged bone.

Flustered, disbelieving, it took him forty minutes to pack his bag with a couple of pairs of khakis, some underwear, shirts, a pair of comfortable shoes, some shaving gear, should have taken five minutes.

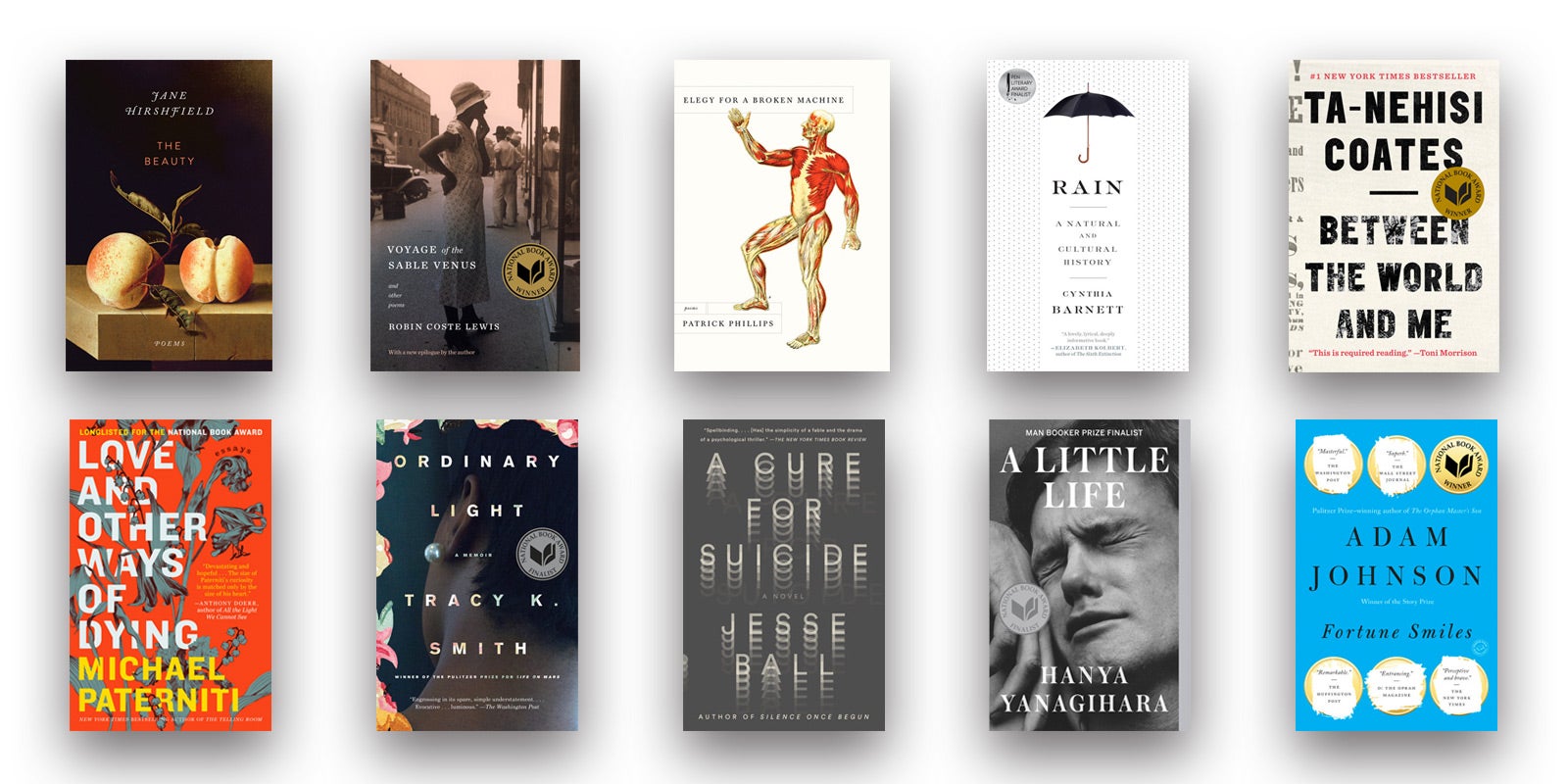

Copyright © 2015 by Michael Paterniti. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.