Little Eva

Was she really beautiful? What did she look like? It is possible to stare for hours at the photographs—never enough of them—in the recent crop of Evita books and find no answers. Soon we will know that she looked exactly like Madonna, but for the moment it is possible to say only that once she had become Evita her image was that of a different order of being—of a Virgin, perhaps, or a saint. A flickering apparition with attributes rather than features: the radiant impact of the gold-colored hair, something haunted about the eyes, the lingering sad ecstasy of the smile. The posters, the photographs, the blurred documentary footage all confirm it: she was not a person but an embodied gesture.

Not in the early photographs, though. Here she is, for example, in a picture reproduced in Eva Perón, a new biography by Alicia Dujovne Ortiz, [Published in English as Eva Perón: A Biography (New York: St. Martin’s, 1997).] which shows her in the days before her hairdresser discovered that history needed Evita to be a blonde. It is mid-1944, and, thanks in large part to certain skillfully wielded influences, the provincial actress Eva Duarte, possessed of an unreconstructed working-class accent and an unfailingly gauche manner, has obtained her first feature role, in a movie called Circus Cavalcade. In the promo shot, brunet ringlets surround a pale, slightly thin-lipped face. The nose has a hint of the ski jump, but the eyes are large and their expression is pleasant. A big bow is strategically placed over what was a famously flat chest, but it does nothing to disguise her terrible posture. She projected no sexuality, and there is nothing in the photograph to indicate that Eva Duarte’s public personality might have been memorable either—an impression, or lack of one, confirmed by the kindest word that critics ever used to describe her acting: “discreet.” There is nothing in the image, certainly, to suggest transcendence.

And yet the sense we have of Eva Duarte’s destiny is so strong by now that it is almost impossible to believe that at the time the picture was taken she did not know, as we do, that this bland and to all appearances untalented girl, born illegitimate and on a ranch, was soon to become Evita. It would have been logical for anyone with more ordinary ambitions to think instead that 1944 was already the crowning year of her life: she had a movie role, a nice apartment filled with knickknacks, a modest degree of name recognition, and a new military lover—a very important one—with whom she was passionately, overwhelmingly involved.

Because the meeting between Eva Duarte, aspiring radionovela actress, and Juan Perón, putschist colonel, is the stuff of legend, it is impossible to be completely certain of anything about it, including the date and the circumstances of their first encounter. By most accounts, including Perón’s, it took place on January 22, 1944, and the occasion was a benefit for earthquake victims, sponsored by a group of army colonels who had overthrown the civilian government six months earlier. Eva Duarte, who had recently gone for months without acting in any of the radio soaps that were the mainstay of Argentine broadcasting, and who had in the past endured typically sordid casting-couch arrangements in order to get work, was working now, thanks to her new friend Lieutenant Colonel Aníbal Imbert, who was in charge of the post and telegraph offices (and communications in general) for the new regime. Imbert had got her the starring role in a new radio series, based on the lives of famous women in history—Isadora Duncan, Elizabeth I, Mme Chiang Kai-shek—but it was Eva alone who then, drawn to the populist rhetoric of the new regime and always looking for an opportunity to stand out, maneuvered herself into the position of spokeswoman for the Radio Association of Argentina, and into events like the earthquake benefit.

In Eva Perón, Alicia Dujovne recounts the various versions of how that fateful evening Eva Duarte found herself being led to one of two empty seats on the platform, next to Imbert, who was waiting for his friend Juan Perón. (The most amusing story comes from the benefit’s emcee, Roberto Galán, who claims that Eva stood beneath the stage, tugged on his pants leg, and said, “Galancito, darling, introduce me. I want to recite a poetry.”) Dujovne sensibly speculates that instead it may have been Imbert himself—by that time heartily sick of Eva’s anxious, clutching personality—who introduced her to Perón, at an earlier party. But in the brilliant novel Santa Evita,[New York: Knopf, 1996.] Tomás Eloy Martínez recounts history as it should have been, and as it was told to him long ago in Madrid by an aging Juan Perón: Eva’s heart belonged to Perón even before they met. It had become clear that the colonel, who was in charge of labor relations, was emerging as the real authority in the new regime. He looked magnificent in uniform. His smile was benevolent and virile. His radio speeches had thrilled her. (“I am only a humble soldier who has been granted the honor of protecting the working masses of Argentina.”) She was twenty-four, he forty-eight. On the platform, sitting next to Imbert, she turned her great dark eyes on Perón as he walked to his seat.

“Colonel.”

“What is it, my girl?”

“Thank you for existing.”

She got his attention. Perón was ambitious but lazy, wily but aloof, and interested, as life would prove, in few things besides himself, politics in relation to himself, and his French poodles (and a fourteen-year-old mistress he took on after Eva’s death, to whom he wrote fond letters about the French poodles). But Eva could force herself into his hitherto sterile emotional life because from their first meeting she offered herself up to Perón as his worshiper, and from that moment virtually until the instant of her death, eight years later, she did nothing in public or in private that was not in some way an act of devotion to him, an oblation of frankincense and myrrh. “Mi vida por Perón!” she cried a thousand times before the roaring crowds, and then she died. There are parallels that could be drawn between her life and the lives of other obsessively ambitious women who have forced their way out of poverty and to fame through the skillful, untiring manipulation of their own images—Madonna, let us say—but instead popular memory finds parallels between Evita’s life and the lives of the saints, because she did it all for someone else.

In life, Evita was and wished to be only an instrument of Perón. (In death, she took on a life of her own, but we will come to that.) Toward the end, someone wrote an autobiography for her (she was barely literate), and it was called what she called Perón in all her speeches:

My Reason for Living. [

La razón de mi vida (Buenos Aires: Ediciones Peuser, 1952).] If anything, she was even more effusive about her husband in private. Joseph Page, in his excellent introduction to the English-language edition of a second text ghostwritten for Evita, this one as she was dying, called In

My Own Words,[New York: New Press, 1996.] quotes a letter she wrote Perón: “Tonight I want to leave you this perfume above all else so that you will know I adore you and if it is possible today more than ever because when I was suffering I felt your affection and goodness so much that until the last moment of my life I will offer [misspelled] it to you body and soul, since you know I am hopelessly in love with my dear old man.” By most accounts, Perón was sexually indifferent. Dujovne assumes, without telling us why, that Eva Duarte was actually frigid. Yet there is no doubting the passionate and romantic nature of Eva’s commitment to her husband. By a lucky accident of history, her passion was fueled by precisely the same emotions that drove millions of Argentines to what Eva eventually baptized la fe peronista—the Peronist faith.

The facts of Evita’s early life coincide nicely with those of the poor she came to represent: she was, like so many others, born of a destitute woman who found it expedient, and possibly gratifying, to take a wealthy and powerful lover. (Juan Duarte was a landowner and small-town caudillo, or political boss, in a rural area about ninety miles west of Buenos Aires, and he was properly married. Juana Ibarguren was a woman he spent many nights with and was the mother of five of Duarte’s children, of whom Eva María, born in 1919, was the youngest.) Like so many children born of these arrangements in a country where upper-class snobbery reaches extremes of refinement and viciousness, Eva was humiliated by her bastard status. (Juana Ibarguren and her children, who lived in a one-room house, were kept away from Juan Duarte’s elegant funeral, but were allowed to say a quick farewell to the corpse at the wake.) Eva migrated on her own from the sticks to Buenos Aires at age fifteen, and, like so many of the expanding capital’s other new residents, she looked for opportunity and found it lacking. She shared with her class a gnawing, all-encompassing resentment that was the precise counterpart of the seething contempt the ruling class cultivated for the plebes. Most important, neither she nor her fellow poor were inclined to be fatalistic. The Argentina that Eva Duarte grew up in was a nation of recent immigrants—Italian anarchist farmers, Spanish socialist shopkeepers, conservative German merchants—who had brought their politics with them when they migrated, and who firmly believed that they deserved the better life they were willing to work so hard for.

Perón—himself born out of wedlock, and pursuing upward mobility through an army career—was their catalyst. He was a cynical politician who systematically played off his followers against one another, often with tragic results, and his authoritarian approach to government probably grew out of his intense admiration for Franco and Mussolini. It may well be the case that he (and Eva) provided shelter for Nazis fleeing Europe after the Axis collapse, in exchange for a significant part of the Third Reich’s treasure—Dujovne works hard to try to prove it in her biography—but generations of Argentines have remained impervious to these accusations, because of what Perón gave them: a political movement that legitimated and ennobled the working poor, and a decisive restructuring of the state which—by nationalizing key resources, establishing generous social-welfare programs, and institutionalizing a crony relationship between organized labor and the government—transformed Argentina from a sugar daddy for the rich into a sugar daddy for the poor. Perón was only one of several upstart colonels when Evita thanked him for existing, and his speeches did not then, or ever, reveal the kind of substantial political thinking that gets translated into lasting programs or gets used to interpret reality in other parts of the world, but he cannot simply be written off as a demagogue. He had a vision of a free Argentina: a nation that under his verticalista guidance would steer clear of both sides in the Cold War, and in which law and order would prevail, government would be responsive to the needs of its citizens, and workers would get the respect their efforts deserved. In that sense, he was revolutionary, and Eva Duarte, like millions of others, responded instantly to his appeal. As for his aloof, diffident personality (he liked to describe himself as “a herbivorous lion”), it, too, was a virtue, for it turned him into an empty vessel that Evita could fill with her faith.

Eva Duarte’s role in history was determined within months of her first encounter with the colonel. One day she was a source of hilarity for upper-class women, who made a point of tuning in to her “Famous Women” broadcasts. (“What a daily pleasure, this nasal voice who played [Catherine of Russia] with rural tango accents!” one said.) The next, she had secured her movie role in Circus Cavalcade, because she was already the established mistress of Juan Perón, a man not known for passion, who had nevertheless rented an apartment in Eva’s building so that he could be near her without violating the moral code. His new lover was not easy or pleasant to live with—she threw tantrums, demanded in public that he marry her, and soon displayed her contempt for all but his most slavishly devoted political associates—yet despite these defects she was the perfect woman for him, because she pushed him beyond his own apathy. Within weeks, Perón had taken the measure of her political genius, and he sent her out on the hustings. He looked on approvingly as she forged her new public persona. Dujovne, whose insightful biography is marred by the lack of sources for material that is often controversial, and by an irritating Argentine penchant for psychobabble, is invaluable when she is narrating Evita’s act of self-creation.

The clothes changed first, in 1945. Dujovne cites a recollection of Francisco Jamandreu, designer to the stars:

“Do not think of me the way you think of your other clients,” Eva would tell him. “From now on, I will have a dual personality. On the one side, I am the actress to whom you can give poufs, lamé, feathers, sequins. On the other, I am what the Big Shot wants me to be, a political figure. On May 1, I must accompany him to a demonstration. People will gossip, it will be the first appearance of the Duarte-Perón couple. What will you create for the occasion?”

Jamandreu settled on a double-breasted houndstooth suit with a velvet collar, so elegant and practical that even Eva Duarte could be taken seriously while sheathed in it.

Then came the hair. The first photograph of Eva as a blonde appeared in a magazine on June 1 of that same year. Dujovne writes:

Since hair dyes had not yet been perfected, the color’s ambition was, in fact, not to appear natural. It was a theatrical and symbolic gold, a gold that imitated the effect of the golden halos and backgrounds of the religious paintings of the Middle Ages. . . . From then on, she would polish and refine her personality by gradually eliminating all excessive ornaments: first the banana earrings, then the flowered dresses.

She wore the new look when she was stumping for Perón during the following months, and probably during the third week of October 1945—a week that decided the colonel’s destiny. The other colonels who had overthrown the civilian government with him were now enraged by, among other things, his increasing prominence, his populist tendencies, and his impertinent mistress. They put him under arrest on October 13. There was a significant degree of support for the move, and Eva herself was mauled that day by middle-class university students. But on October 17, Perón’s working-class followers descended on Buenos Aires from every part of the country, in numbers that even the wily colonel could not have expected. Whether they were organized by Evita remains a matter of debate. (The evidence indicates that they were not, but this is a conclusion that Peronists and anti-Peronists alike consider a heresy.) What is certain is that Perón himself did little except sit quietly in a room of the military hospital where he was being kept prisoner, considering whether he should marry Eva and get out of politics altogether. In short order, though, his enemies decided that the only thing to do in the face of the tumult was to release him and call for elections. These Perón won handily, with the constant help of the woman who was now known as Eva Duarte de Perón, because shortly after his October triumph, El Conductor, as he was now called, had at last married her. In exchange for his vow, she gave up her acting career.

If this were a story about a man, no one would be asking what color suit he wore to the inauguration, but this is a story about a Latin woman of the 1940s who was obsessively interested in clothing, jewelry, and self-presentation, and was also uncannily perceptive about what the people she wanted to address looked for in her. “The poor like to see me beautiful: they don’t want to be protected by a badly dressed old hag.” The transformation of Eva Duarte was almost complete, but mistakes were still being made. After Perón took power, he dispatched the First Lady on a goodwill tour of Europe, and she sent a ripple of delighted horror through Paris society by appearing at a reception in her honor in a strapless gold-lamé evening outfit worthy of a cocotte. But she returned to Buenos Aires with a full and judicious wardrobe on order from Christian Dior, and eventually her confessor, Father Hernán Benítez, prevailed on her to sacrifice all makeup except lipstick. As Dujovne points out, the effect of this act of contrition was to make her timelessly fashionable. Then the same hairdresser who had made her blond pulled her hair tightly back from her pale, broad forehead, wove a braid, and bound it in a shimmering knot at the nape of her neck. And, finally, Eva María Duarte de Perón adjusted her name. It is unusual in Latin America for a woman to be known only by her husband’s name, but she wanted to be called Eva Perón, a Perón in her own right. She had pared herself down to the essentials, and she had become one of the most powerful women in Argentina and in the world.

Evita did not live on in memory because of the way she looked but because she looked beautiful, bejeweled, and radiant while consuming herself in a flame of devotion to her husband and the poor. The dramatic change in her appearance has historical significance, and Dujovne does a fine job of linking Evita’s outward changes to the development of her personality, but all the author’s laborious research cannot account for the essential transformation of Eva Perón: from a pushy, selfish twenty-six-year-old starlet (her age when Juan Perón first came to power) to a flagellant compelled to take on the suffering of an entire nation and make it her own. Was Evita really still Eva Duarte after she managed to give the slip to that telltale accent, and was she more sincere when she insinuated to a society lady that she would love the woman’s diamond necklace as a present or when she gave her jewels away to the poor? Was the suffering mother of all Argentines the same as the ruthless politician? If she wasn’t, then who died? (Some, of course, think she is still alive; the possibility of her reincarnation is a rumor that flares periodically through Argentina.) It is, at any rate, as difficult for those who believe that her spirit lives to describe her as it is for those who knew and loathed her in the flesh: She was grasping, shrewish, and so calculating that she orchestrated her acts of charity to distract attention from all the money she and her husband salted away in Switzerland. Or else she underwent a spiritual conversion when she met Perón that allowed her to channel the voice of the working masses. But it may be that she underwent a spiritual conversion and remained grasping, shrewish, et cetera. And also ignorant. If Perón had few ideas about how to use his country’s wealth to generate real national prosperity, or how to create a true body politic, Eva, with her youth, her sixth-grade rural education, and her recent frivolous past, had none. She did what she could with the irresistible possibility that was granted her to do good, while living out a fantasy that dated back to the days when she left her hometown for the capital, impelled by the dream of becoming like her idol, Norma Shearer, in the role of Marie Antoinette.

The Peronist myth is that she and the poor identified with each other because Eva too had been poor. But one can wonder if it was perhaps that the poor identified with her rage and fed it, in turn, with their love, and whether it was the unbearable tension at the crux of these emotions that led her to die. Eva Perón died, in 1952, of uterine cancer, because she had refused to have an operation when the disease was first diagnosed, in 1950. She didn’t have time, she said. She was too busy rallying recalcitrant politicians to support the Peronist reforms, lobbying Perón himself to push a women’s-voting-rights act through Congress, and extolling Perón across the country in speeches whose flavor had not a little of the lachrymose radionovela actress she once was (“I come from the people; this red heart that bleeds and cries and covers itself with roses when it sings”) but whose intensity was overwhelming.

All this she did in her spare time. Juan Perón, after taking office, slept calmly through his nights and lived an orderly existence, presiding over the government as it is a man’s business to do. His wife worked through the evenings, slept little, and in the morning—tailored, perfumed, and decked out in diamonds—set out for the Labor Ministry, where she had a suite of offices but no official position. (Eva never would have a government job.) In the ministry’s Great Hall, los pobres (“mis pobres”) were already waiting. The same scene was staged day after day: a line of supplicants, among them the lame, the halt, the destitute; a flock of anxious minions armed with notepads; and behind the vast desk, radiant and ever gracious, the Lady Eva. Did an old crone need dentures? Done. Did a timorous couple come to beg for wedding garments? Hecho. When the money ran out, she unfastened a diamond clip and handed it over. Perón had a horror of physical contact. Evita kissed lepers. She also took lice-infested urchins to the official residence for a rest cure and bathed them herself; started a union for domestic workers; and set up hospitals, children’s homes, and a home for girls who traveled to the big city and found themselves penniless, as she once had.

Joseph Page writes that, even as Eva’s health declined, the Eva Perón Foundation—a conduit set up by Evita for her multiple social works—grew into a “gigantic enterprise dominating virtually all public as well as private charitable activity and extending into the fields of education and health.” Dujovne, noting that no charge of corruption against the foundation has ever been substantiated, imaginatively counters another charge: that its institutions—the provincial girls’ home, for example, in which each floor was decorated in a different style (provinciano, fake English, faux Louis XV)—were merely lavish charity. The “fundamental idea that Evita hammered into the heads of the humiliated and the downtrodden” by practically forcing them to sleep in beds with embroidered sheets, Dujovne writes, was that they deserved such beds.

From the third year of Perón’s first presidential term, Eva was dying, and death’s proximity made her more vehement. All the fame and glory she had accumulated had done nothing to appease her fundamental resentment. She saw enemies everywhere. She acquired some newspapers and closed down others she couldn’t control. She flew into rages in closed Senate sessions and saw to it that government officials who were anything less than obsequious lost their jobs. She fought hard to persuade her husband that the leaders of a conspiracy against him should be shot. (He refused.) In the ghostwritten In My Own Words, someone wrote words very like her own: “Those who speak of sweetness and of love forget that Christ said, ‘I have come to bring fire over the earth and what I most want is that it burn!’ ” and “Fanaticism turns life into a permanent and heroic process of dying; but it is the only way that life can defeat death.”

Perhaps she did consciously decide to die so that she might live. When her health broke down completely and she was forced to agree to an operation, it was too late. Even as she entered the last stages of the disease, though, she was changing. Perón was suddenly less important than the cause, and, despite having said so many times “I am nothing,” she now desperately wanted the vice presidential slot on the ticket for Perón’s reelection. Nevertheless, when a surging, beseeching multitude—probably the largest gathering in Argentina’s history—asked that she join her husband on the ticket, at an electrifying public meeting on August 22, 1951, Perón vetoed her candidacy. He probably sensed that the woman he had always described as his invention was about to break free of his influence, and yet once more Eva obeyed him. Even though she had less than a year to live, it was far too late for her jealous husband to expunge her name. All Argentina knew her no longer as Eva Perón but as Evita only. It was one name, like a saint’s, but in the diminutive, like that of someone fragile whom people hold dear. She was weakening visibly. She weighed eighty pounds.

Her last act of will involved yet another manipulation of her own body: in order to attend Perón’s second inauguration when she was already too weak to stand, she had a plaster support made in which she was encased, upright, during the open car ride, the device covered by a long fur coat. (It may have included an arm prop, for she waved to the crowd the whole way.) On July 26, 1952, while tens of thousands of her distraught worshipers knelt and prayed that she might live, Evita died. She was thirty-three.

Three years later, the life gone from his movement, Juan Perón was overthrown. The herbivorous lion lacked the will to arm the workers with the machine guns and automatic pistols that Evita had bought from Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands for just such an occasion. Instead, Perón left quietly, bound for his long, comfortable exile in Franco’s Spain.

The following is all true, supported by recorded fact and presented almost straightforwardly in Santa Evita, Tomás Eloy Martínez’s fictional chronicle of Eva Perón’s afterlife: A Spanish embalmer, commissioned by Perón even before Evita’s death, transformed her corpse into a radiant effigy. (Ever conscious of her image, Evita on her deathbed requested a postmortem manicure, to change the color of her nail varnish from red to natural.) Peronists worshiped this figure until Perón was overthrown, in 1955, when right-wing military officers snatched the body away. And, according to the book, the embalmer had already made several copies of the body, which for the next fifteen years were part of a shell game played out in Argentina and in Europe. The generals who overthrew Perón found it unchristian to discard the real body, but they feared its power to stir multitudes against them, so, Martínez writes, the copies were deployed around Argentina until a safe, anonymous burial ground could be found for Evita’s corpse. At one point, it was entrusted to an army major, and he put it in his armoire. One evening, he heard steps approaching in the dark and fired his gun lethally at the intruder. The victim turned out to be his pregnant wife. The chief of operations for the abduction of the corpse went mad with the body in his care. Every time he transferred Evita to a new hiding place, flowers and lighted candles appeared there. He watched over her so obsessively that he was finally removed to an insane asylum by his alarmed superiors, and in the late fifties they got the body to Italy and into a funeral plot in a Milanese cemetery, under an assumed name.

In 1971, Perón was living in Madrid with his new wife, Isabelita, a former cabaret dancer with an incongruous schoolmarmish air, and with her private sorcerer, José López Rega. As part of a peace overture to the deposed leader, whose movement continued to flourish in his homeland even as the very mention of his name was forbidden, the military returned to him Evita’s bedraggled corpse. Isabelita combed its hair, the original embalmer restored it, and Perón put it in his attic. It appears to be true—at least, reliable sources claim that it is, and in Santa Evita Martínez makes it impossible to believe that it could not have been—that López Rega then staged a ceremony in which Isabelita lay on top of the coffin while he tried to transmigrate the soul of the deceased Mrs. Perón into the living one.

In the end, Evita—so desperate not to be forgotten, so unaware of how impossible that would prove—didn’t get the mausoleum she had wanted and had helped design, which was to be the size of Napoleon’s tomb. (We know, however, that she got the equivalent: her operatic life was turned into the rock opera that is soon to be a major motion picture.) By the time of Perón’s official return to Argentina from his Spanish exile, in 1973, he was ambivalent about Eva’s fame, if not downright resentful of her, and wary of her Evitista followers, who had taken to chanting at mass rallies that if Evita lived she would be a guerrilla, and were about to go underground themselves. He did not bring the long-wandering body home with him.

The leftist Peronist guerrillas’ archenemy would be the fiendish warlock López Rega, whom Perón appointed minister of social welfare, and who from that position set up the first of the organized death squads that would eventually undermine Argentina. Perón ruled with Isabelita occupying the vice presidency he had once denied Eva, and she succeeded him upon his death, in 1974. Isabelita immediately had Evita flown back from Spain so that Evita and Perón could lie in state side by side. But Perón had not wanted to be buried with Eva. (He never called her Evita.) He was placed in the Perón family crypt, where, in 1987, vandals broke open the tomb in order to saw off his hands.

Eva’s still luminous corpse was taken to the Duarte family crypt, in Buenos Aires’s fashionable Recoleta Cemetery. Having survived the array of indignities inflicted upon it, it has been allowed to lie in peace for nearly twenty years. Beyond Argentina, however, Evita’s life has evidently just begun. It is not the same Eva Perón who coursed so tenaciously through her country’s history that the world craves, but it is Evita all the same: heroic and fragile, grasping and motherly, parthenogenetic—like all real heroines—but in the service of a man, rebellious but condemned by fate, angry but submissive to that fate. A shimmering figure that comes in and out of focus endlessly in order to allow us the hypnotic speculation that all true stars elicit: What did she really look like? Could she have looked like me?

—December 2, 1996

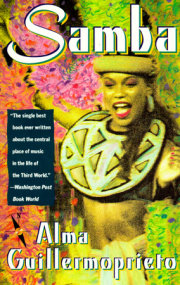

Copyright © 2001 by Alma Guillermoprieto Chapter One. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.