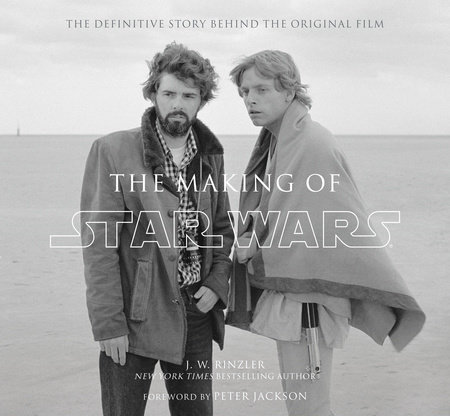

THE SUMMER OF STAR WARS

MAY TO DECEMBER 1977

Chapter One

Star Wars was a hit. It had opened in 32 theaters on May 25, 1977, and then expanded, slowly, into several hundred more. By the end of July, it was playing in packed houses scattered throughout the United States.

"To set the scene for this journal and to establish its point of view, I must go back to the summer of 1977," writes Alan Arnold in Once Upon a Galaxy. "I was with a film unit in Greece when reports began to reach us of an extraordinary movie that had taken America by storm. Some of the technicians on location had worked on the film the previous year and were surprised, even puzzled, by these reports. They could not explain the fever developing around what was being called, for want of a better term, a space fantasy, nor the fact that in American cities people were lining the streets for blocks to see it-and going back again."

"I was making a film in northern Afghanistan," says Robert Watts, production supervisor on Star Wars. "I used to buy Time magazine and Newsweek as it was the only way to keep in touch. I bought my copy of Time one week and opened it straight onto a bunch of color pictures from Star Wars. I thought, Bloody hell! I had no idea it had taken off to such a huge extent."

"I was walking down Hollywood Boulevard after the film came out," says production illustrator Ralph McQuarrie. "It was still playing at Grauman's Chinese Theatre. The sun was setting and there was a little piece of paper blowing along the sidewalk. I picked it up and saw that it was a bubblegum wrapper with Darth Vader on it. I thought, Gee, now I'm one of those people who make those things. It's part of life now."

An astronaut at a party told special effects photography supervisor Richard Edlund, "that he believed it all and was glued to his seat."

"It was a darn good story dashingly told and beyond that I can't explain it," says Alec Guinness, who had played Ben Kenobi. "Failure has a thousand explanations. Success doesn't need one."

"Star Wars tumbled out in the summer of 1977 and just went cuckoo," says Mark Hamill, who had portrayed Luke Skywalker. "It was like the hula-hoop or Beatles rages. After the film came out, I broke up with my girlfriend for a while. I was like a kid in a candy store. Gee! All these groupies. I don't feel I dealt with that very successfully."

"When the film came out, I seemed to do publicity for ages, which meant a lot of travel," says Carrie Fisher (Princess Leia). "It was great. But I only get a sense of Star Wars' importance when a child recognizes me and becomes speechless. Kids don't think I'm on this planet. Very little children even believe Princess Leia is a real human being who lives in outer space."

"What Star Wars has accomplished is really not possible," says Harrson Ford, who had played Han Solo. "But it has done it anyway. Nobody rational would have believed that there is still a place for fairy tales. There is no place in our culture for this kind of stuff. But the need was there; the human need to have the human condition expressed in mythic terms."

"Millions of people go to the cinema," says composer John Williams. "It's stimulating to hear people whistling your tunes."

The writer and director of Star Wars, George Lucas, had returned that June from Hawaii, where he'd retreated to escape the work that had dominated his life since 1973. He, too, had been surprised by the film's initial success and was relieved by its perseverance. It seemed more than likely that Star Wars was going to make its money back and then some. While on the island, he hadn't neglected his passion for film and had enticed his friend and fellow director Steven Spielberg to work on another project of his-Raiders of the Lost Ark-which would feature an adventurer-archaeologist named Indiana Jones.

"I took Francis Ford Coppola to see Star Wars in a regular theater in San Francisco," says Lucas. "That was probably the first time I saw it with a real audience. It was enjoyable, but the thing of it is, by the time you get that far down on a movie, you're so numb and so tired and so emotionally involved that it's very hard to jump up and down and get excited. You feel good, but it's a very quiet kind of thing."

"When it became a phenomenal success, it was amazing," says Bunny Alsup, assistant to the producer of Star Wars. "I don't think anybody in the world expected it and it was astonishing. Back in the preview days, I remember we were trying to fill a theater with all age groups, so I was personally calling college campuses and asking, 'Would anyone like to go see this movie?'_"

BADLANDS

After giving a few interviews, George Lucas stopped doing publicity for the film. It was bringing too many people with scripts to his door asking for money or, occasionally, making threats. The success of Star Wars was already different from the success of his previous film, American Graffiti (1973), inspiring massive emotional reactions domestically and around the world as it opened in foreign markets. It had enormous licensing possibilities and warranted a sequel.

A follow-up, however, was going to take an enormous amount of work from someone who was in the middle of recharging his batteries. Lucasfilm wasn't a big studio, or even a small studio. It had a makeshift office called Park House, just north of San Francisco in San Anselmo, and-on a parcel owned by the company-a single trailer sitting in a parking lot across the street from Universal Studios in Los Angeles.

The triumph of Star Wars was a mixed blessing. Making that movie had been a four-year horrific seat-of-the-pants experience-one Lucas never wanted to live through again. But he had always envisioned a grander, very different film from what he'd ended up with, so a sequel would allow him to finish the saga-and to tempt the fates once more.

"It took so much effort just to get up to speed in order to make the first film and create this great world that I didn't have the time to have any fun, to run around in it," says Lucas. "Now that I know the world and I can see it, it brings up all kinds of ideas and funny moments and adventures. In the first one, you are in a foreign environment-you just don't know what's going on-and it was the same for the author as it was for the audience. So I always felt if I went back to those environments using the same characters, I could make a helluva better movie."

Several rumors were already extant in the media concerning follow- ups. One source said that two Star Wars sequels had been shot while the first film was being made. The second movie, reportedly, would decide who gets the girl and feature a new battle against Darth Vader and his followers. The third movie would have Ben Kenobi return and try to restore the Jedi Knights so they could combat evil throughout the galaxies.

Twentieth Century-Fox, the studio that had financed and distributed the film, responded officially that no work had been done on the sequels. Sources also stated that George Lucas wanted only to "supervise" future projects. That part was true. Lucas stated publicly several times that he was retiring from the director's chair. "You end up not being happy anymore and working yourself to death," he says. "Star Wars became a priority; it was one of those things that had to be done: 'But what if something happens to one of the actors? We can't afford to keep the sets around any longer because it costs a lot of money.' It put me in a bad place personally."

DISAPPEARING MAGIC

During the summer of 1977, Lucas used the law office of Tom Pollock, Andy Rigrod, and Jake Bloom to begin negotiations with Fox, which had the right of first negotiation and first refusal. Back in 1976, the trio had succeeded in procuring the sequel rights and a 50-50 licensing split for Star Wars. At the time, the studio thought it had given up worthless items, because executives had no faith in the film. Nevertheless, those negotiations had taken more than a year. While Lucas anticipated a much shorter wait this time, he used the bartering period to start organizing his nearly nonexistent company.

Many potential problems loomed, not least of which was that his visual effects company, Industrial Light & Magic, had ceased to be upon the release of Star Wars. Not a single employee of ILM was on the payroll as of June 1977. Those men and women had of course sought work elsewhere. Many former key members had simply reorganized in the facility's original warehouse in Van Nuys, forming Apogee, whose founding members were: John Dykstra, Grant McCune, Bob Shepherd, Richard Alexander, Alvah Miller, Lorne Peterson, and Richard Edlund.

"Right after Star Wars came out, there was a period where George didn't know what to do," model maker Steve Gawley says. "He owned the equipment. But in the meantime, he didn't need it, as far as I understand. And so the same group of folks got back together and rented the equipment, and we made a television miniseries for Universal called Galactica."

"They rented the equipment back to John Dykstra," says model maker Lorne Peterson of the effects supervisor on Star Wars. "And so we were doing Galactica. Dykstra and Apogee ran their group as a cooperative. They all shared in responsibility and shared in profits equally. At least, I think it was equally. I also had my own really small company. We were struggling and then we were also working on Galactica."

"We got hornswoggled into doing this project with Glen Larson for Universal, the Galactica," says Edlund.

"Glen Larson came in to ILM, the old ILM in Van Nuys, after George had moved out," says art director Joe Johnston. "But all the people were still there and he hired the entire group, including me, to design, build, and photograph all these visual effects."

"I left ILM and then it turned into Apogee and they were doing Galactica," says Ken Ralston, assistant cameraman. "I got on two smaller films that never saw the light of day. But I learned a lot during that time, six months on one, that was a disaster! But you have to learn those things."

While not everyone at the former ILM stayed at Van Nuys-special effects photographer Dennis Muren had departed in March 1977 to work on Steven Spielberg's Close Encounters of the Third Kind, which was released in November-the reality was that Lucas was going to have to start a visual effects company for a second time if he wanted to make a second Star Wars. And the Galactica project was going to be a thorn in his side for some time to come.

BUILDING THE EMPIRE BENIGN

Before Lucas could even begin to reconsecrate his visual effects team, he would have to form up his corporate headquarters.

"I was in private practice in San Francisco," says attorney Douglas Ferguson, "and my secretary told me that a fellow named George Lucas wanted to talk to me for business advice. I said, 'I don't know any George Lucas.' And she said, 'You must not be reading the newspapers because he's got a movie out called Star Wars that's a big, big hit.' And that led to a meeting where George came to my office. We got along famously, so we began sketching out the corporate empire that George had envisioned for his company, now that he had the wherewithal to do something."

Ferguson had been the lawyer for John Korty, another Bay Area filmmaker and Lucas's friend. "Doug did a lot of my personal legal work," says Lucas. "Tom Pollock was my production lawyer. He'd done the legal work and set up a lot of my movies, Star Wars and Graffiti, and the incorporations of my first companies."

Ferguson would also handle, primarily, the corporate interactions between Lucasfilm and its eventual subsidiaries. One of those, Black Falcon, would eventually take over merchandising and licensing; others would handle movie productions, such as the sequel to American Graffiti, another film already in the pipeline, and Radioland Murders, an ongoing project.

"The business side of the film industry I don't much like or want to get involved in," Lucas says. "I set down parameters that I want my company to maintain and they reflect my philosophies, my beliefs from when I grew up, which I feel are fairly practical but still basically right. But the corporate environment in Hollywood isn't any different from the corporate environment in the energy business. It's all about making money and it's all about making deals and it's all about screwing this person or that person. It doesn't have anything to do with making movies."

In addition to his big-picture plans, Lucas was looking for someone who could help run his day-to-day business. "I'd had about 12 years' experience in the film industry in a lot of various capacities," says Jane Bay. "But I wasn't sure that I wanted to continue to work in the film industry because I didn't like what was happening. Basically, the suits were taking over. It was after the decline of the studio system, and the businesspeople were starting to run the industry and I just didn't like the way that it was going. So on the Fourth of July, I called Tom Pollock, a very close personal friend, and said I'm going to be moving to San Francisco. And he said, 'Oh, Jane, I just talked to George Lucas yesterday and he needs somebody to be the office manager for Lucasfilm.'_"

"Nobody wants to invest in the esoteric craft of visual effects," Lucas says. "You know, just for the sake of doing it. I started a lot of other companies, but that was by accident. I needed to have a sound facility up here. You have to have a place to pre-mix your movies. You don't want to go to Los Angeles to do it, so you start a little sound company. We had to create it all. We were basically carving an industry out of the wilderness here."

Four days later, Bay went over to Universal Studios. There George had a "little satellite office" not far from Spielberg's where they talked about the state of the film business. "George was telling me that he didn't know if I'd be happy moving to Marin County because he wasn't part of Hollywood and I had this long history in Hollywood in the studios and with independent filmmakers. He said, 'I'm just afraid that you're gonna be bored.' But I just kept saying, 'I left the film industry two months ago to get away from all of it.' So he said, 'Okay, well, you come up to Marin County and see how you like it.' I didn't realize that he had hired me on the spot."

Copyright © 2010 by J. W. Rinzler. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.