CHAPTER ONE

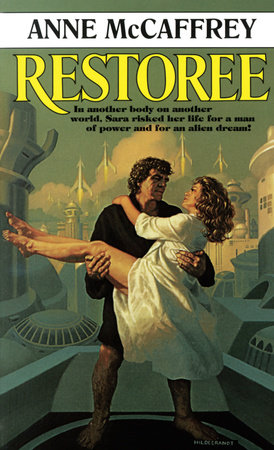

THE ONLY WARNING OF DANGER I had was a disgusting wave of dead sea-creature stench. For a moment, it overwhelmed the humid, baked-pavement smell that permeated the relatively cooler air of Central Park that hot July evening. One minute I was turning off the pathway to the Zoo in search of a spot that might have a breeze from the lake and the next I was fainting with terror.

I have one other impression of that final second before all horror overcame me: of a huge dirigible-shaped form looming lightless. I remember that only because I thought to myself that someone was going to catch hell for flying so low over the city. Then the black bulk of the thing seemed to compress the stinking air through my skull, robbing me of breath and sanity with its aura of alien terror.

Of the next long interlude, which I am informed was a period of withdrawal from a reality too disrupting to contemplate, I remember only isolated incoherencies. It is composed of horrifying fragments, do-si-do-ing in a random partnering of all nightmare symbols, tinted with unlikely colors, accompanied by fetid odors, by intense heat and shivering cold and worst of all, nerve-memories of excruciating pain. I remember, and forget as quickly as possible, dismembered pieces of the human body; the pattern of severed blood vessels, sawn bones, the patterns of the fine lines on wrinkled skin. And throat-searing screams. And a voice, dinning into the ears of my mind, repeating with endless, stomach-churning patience, collections of syllables I strained desperately to sort into comprehensible phrases.

Red, yellow, blue beads rolled, parabolically, evading a needle and its umbilical string. A spoon dipped into a blue bowl, into a red bowl; a spoon dipped into a red bowl, into a blue bowl, until my body was forced into the mold of a spoon and itself was dipped into the bowl, my greatly enlarged mouth the bowl of that spoon. Plaits of human hair swayed toward oddly shaped sheets of pale white leather. The gentle voice with the iron insistence of the dedicated droned on and on until each repetition seemed to trampoline into the gray matter of my mind.

Then, after eons of this inescapable routine, I began to clutch at snatches seen normally and rationally; a face on a sea of white which stretched limitlessly beyond my blinkered perception. I would be aware of bending over this face. I kept trying to make the face resemble someone I knew: one of the junior account men who invaded the source library of the advertising agency where I worked; one of the anonymous faces on the buses I rode from my 48th Street cold-water flat.

At other times, I would find a tray of food held in front of me and associate myself as the carrier. This troubled me even more because of all things, I hated serving food. In college I had paid for my board working as a waitress and sometimes a cook in private families, resenting the necessary exigencies of a junior female member of a large family. It seemed to me my earliest recollections were of setting or clearing the table and serving food. But the feeling of the entire scene here had an alien quality to it, despite the fact my coherent vision was limited. The tray and dishes had a different touch and the smell of the food was unfamiliar.

The next identifiable sensation was that of the warmth of sun on my shoulders and the caress of wind, of green light in my eyes. I heard screams that can only be heard and not described, but they might have been from earlier sections of the nightmare. I had the feeling on my hands of the slippery softness of soapy water. Then the face on the vast expanse of white would reappear. I gradually became aware of an unfailing order in the procedure of my dreams. Face, food, water, sunshine, face, food, water, dark. The repetition was endless and I was passive to it, prompted by the droning voice, no longer gentle, but equally insistent.

Slowly, not just that face on a sea of white but peripheral details took form and coherency. The face would belong to a man, an ugly man with vacant eyes, black hair, sallow pitted skin. The fact that he bore not one morsel of resemblance to any of my brothers or any of the overbright young men at the agency gave me distinct pleasure. His face was on a pillow which was on a bed of hospital height. And always I was in the position of looking down, not being on a level, with him. Had he been bending over me, I might just have been alarmed that all the tales of rampant white slavery in New York City drilled into me by my provincial parents were indeed true. My first conscious query was why was I not the patient since, obviously, something was very wrong with me.

The mere sensation of sun warmth gradually expanded to include oddly shaped trees with willowy, waving fronds, and with the feel of the wind was the cool fragrance of floral odors.

The ground no longer hovered somewhere beyond my comprehension but was suddenly squarely under my feet. I was standing on a walk, bordered with blooms I never remembered seeing before. The trays I carried contained individual colored dishes with foods that smelled appetizingly and I fed them to the face in the sea of white.

I cannot judge the length of this semiconscious state. I was a passive observer, comparing the anomalies with personal recollections and finding no parallels. I was, however, not the least bit alarmed by all that, which should have alarmed me, as I am normally very curious, in a discreet way.

I do know that the transition into full consciousness was brutally abrupt. As if the focus of my mind, so long blurred, had suddenly been returned to balance. As if a kaleidoscope had astonishingly settled into a familiar design instead of random, meaningless patterns.

Out of the jumble, my grateful eyes reviewed an entire panorama of sloping bluish lawns, felicitously set with flowering shrubs and populated by couples strolling casually down the paths. Each woman wore a gown the exact cut and color of the blue one I wore. Each man had a blue tunic and a coat gruesomely reminiscent of a straitjacket. Beyond the bluish swath, lay little cottages of white stone, with wide windows, barred by white columns at narrow regular intervals. Directly in front of my face was a shimmering opacity I recognized, by some agency, as a fence and dangerous to me.

I was not, however, one of a couple. I was in a group of eight people, strolling the walks, and the other seven were men. Only one, the man directly to my left, wore the strange jacket.

A voice, issuing from the left side of the man in the jacket, spoke an irritating combination of comprehensible words and jumbled syllables.

“And so . . . he is as well as can be expected. Certainly his physical appearance has improved. Notice the firm tone to his flesh, the clear color of his complexion.”

“Then you do have hopes?” asked an urgent, wistful younger voice. Its owner I could see without noticeably turning my head. He was a young man, tall and slender, with a sensitive, pale-gold tired face dominated by deeply circled eyes. He was dressed in a simple but rich fashion. His concerned attention was on the man whose harness controls I now found myself holding.

“Hopes, yes . . . [another incomprehensible spate of words. It seemed to me I was hearing another language in which I could not yet think] . . . we have had so few successes with this sort of. . . . Our skill does not include mental breakdowns . . . the strains and concerns of affairs in your behalf and for his country . . . but you may be sure we are taking the very best care of him until that time. Monsorlit’s . . .”

This was not the reassurance the young man wanted. He sighed resignedly, placing a gentle hand on my charge’s shoulder. It was the lightest of gestures, but it stopped the man stolidly in his tracks. In the vacuousness of the face, there was no comprehension of the action, no reaction, no sign whatever of intelligence.

“Harlan, Harlan,” the youth cried in bitter distress, his eyes brimming with tears, “how could this have happened to you?”

“Come, Sir Ferrill,” commanded a stern voice with no vestige of sympathy in its hardness. “You know that emotional stress can bring about another one of your attacks. You have little enough strength as it is.”

The speaker fetched round in my sight. Immediately I saw his face, I disliked him. I considered myself scarcely a proper judge in this newly rational state of mind, but the instinct to hate him was as sharp as the fleshy face of the man was bland. His eyes, close together on either side of a large nose, were disturbingly cold, calculating and wary. His full sensuous lips sealed tightly over his teeth and his heavy jaw was implacable. His heavyset figure was ponderous, not just fleshy or muscular but unwieldy.

“Your solicitude for my health is touching, Gorlot, but I will judge which emotions I can afford,” snapped the young man with such regality the implacable man demurred.

The youth continued to speak, ignoring this Gorlot.

“Since that is his condition, I must leave Harlan here,” he said to a corpulent, moon-faced individual who bowed with oily obsequity at each phrase. “But . . . if I am not informed the moment an improvement is noticed . . .” and the youth left the threat in mid-air with the authority of one who is used to complete obedience.

The unctuous man bowed again to the back of the youth who turned and walked with brisk steps down another path. The smile on the fat man’s face did not indicate obedience to the injunction. Nor did the knowing look this Gorlot exchanged with him. The others in the party walked into my line of vision and followed the youth and Gorlot.

When they were out of hearing, the fat man turned to me with a sneer and snapped a command, “To the house,” and I, obviously from some well-rehearsed practice in that dim past from which I had so recently emerged, turned myself and my charge around and took a path toward a little cottage among the trees.

At the door stood an armed attendant, a brutish, coarse-looking person who spoke as we approached but spoke as one who knows he isn’t heard.

“Back in your cage, most high, noble and exalted Regent.” He threw open the door he had just unlocked. With a brutal shove he pushed my charge into the house. With an equally brutal and obscene caress, he pushed me inside and snapped the door lock.

Copyright © 2002 by Anne McCaffrey. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.