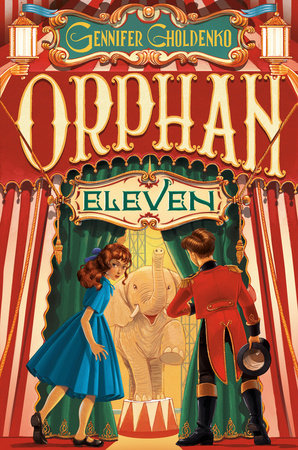

chapter one

Home for Friendless Children

Most kids who ran away got caught. Or they came back on their own sorry feet. Nobody had anywhere to run to or they wouldn’t be in the Home for Friendless Children in the first place.

But it wasn’t every day they were allowed outside the gate.

Even so, Lucy wasn’t about to run. After five years of looking at that wrought-iron fence, it had become as much a part of her as the metal cot she slept on. There wasn’t anything else that was hers. Unless you counted a folded piece of paper, the list of this week’s vocabulary words, the blue button, and the baby tooth in her pocket, and the extra pencil stub stuck in the hem of her dress.

What with the downpour, today was a lousy day to run anyway. Rain dripped off Lucy’s chin and flattened the thick mass of her curly red hair. Rain made her stockings squishy in her too-small shoes. Rain soaked her wool coat, making it feel like the weight of her eleven years was on her back.

It wasn’t like she’d get far with Matron Mackinac not more than five feet from her. Mackinac had piercing eyes, lips the color of dead fish, and a heart like a lump of coal—black and dusty and small.

Lucy had trusted Mackinac once. She’d tried her best to please her by coming early to choir, earning first desk in the schoolroom, and scrubbing the muddy footprints from the hall outside her office. She’d even told the other orphans not to bad-mouth Mrs. Mackinac. Now she hated herself for it.

For the last year and a half, Mackinac had humiliated Lucy every time she opened her mouth. “What a disappointment you are, and I had such high hopes,” Mackinac had said in front of everyone. “You’ll never amount to anything.” The harder Lucy tried, the more Mackinac mocked her.

Where Mackinac had only occasionally noticed her before, now she singled her out for daily torment. In the dark orphanage nights, Lucy wondered if Mackinac and Miss Holland, the lady from the university, were right when they said something was terribly wrong with Lucy. “You are an embarrassment to the orphanage. Everyone can see it.”

Now Mackinac hovered over Lucy and Bald Doris as they shoveled river sand into burlap bags to staunch leaks in the staff house.

But they were outside the fence and the clean smell of the rain and the glimpse of the world beyond the trees sent a wild thrill through Lucy.

If Lucy’s best friend, Emma, had been there, they could have run together. Emma saved Lucy a place in line, shared the handfuls of sugar she got from the cook, and made Lucy laugh when she missed her big sister, Dilly. “Everybody misses someone. Best not to dwell,” Emma said.

But last week a lady had signed the papers to adopt Emma. With Emma gone, every day was orphanage gray.

Lucy did not want to go anywhere with Bald Doris. Doris was a girl you made sure was in front of you in line so that you could see what she was up to. She lied as easily as other girls tied their shoes. About as often, too.

The rain hammered down on Lucy’s head and battered her shoulders.

In weather like this, it didn’t matter if Lucy spoke or not. No one could hear what anyone said.

Matron Mackinac pulled her oxfords out of the mud and slipped a cough drop between the gap in her teeth. “Lucy, get working!”

Lucy was shoveling. Bald Doris was leaning against the wall. But as usual, it was Lucy whom Mackinac scolded.

“We aren’t even halfway—” Rain drowned out Mackinac’s words. “Stay here,” she shouted, and ran across the grass to the boys’ house.

Lucy’s heart knocked like a woodpecker in her chest. Orphans were never left alone outside the fence.

If only Lucy had had time to plan. Then she’d know which direction to run. No matter which way she chose, Bald Doris would tell Mackinac, but Lucy had fast feet.

Only now it was too late. Mackinac was coming out of the boys’ cottage. Lucy had lost her chance.

The disappointment tasted like blood in Lucy’s mouth.

Mackinac struggled to close the rain-swollen door. Next to her were two boys carrying shovels. One boy was Lucy’s size—small for an eleven-year-old. He had dark hair and a bounce to his walk like the ground sprang him up with every step. The other was as big as a barn door, with falling-down trousers that seemed to need his regular attention. Both had on the charcoal-gray coats all the orphans wore.

The bigger boy nodded to Doris. Doris made a face at him. The boys dug in, shovelheads clinking against each other in the river sand.

Matron Mackinac walked along the line of sandbags set against the side of the house, one hand on the skirt of her umbrella to keep the wind from turning it inside out. She slid the candy around in her mouth, her eyes flicking between the girls and the boys. “Don’t move. I’ll be right back,” she said, and hurried off, her oxfords making squelching noises as she pulled her feet out of the mud.

Lucy took a step forward. But the wind rose, shoving her back, and her right foot returned to its place by her left.

Then the wind died down and the sound of the river filled her ears. All of the awful things that had happened to Lucy at the orphanage came rushing through her head: the humiliating lessons with Miss Holland, the cruelty of Matron Mackinac, the cold sweats on the mornings Mackinac read the list of orphans to be sent to reform school.

Lucy took off across the wet grass and through the trees. She leapt the ditch to the dirt road, her legs sailing under her.

She had just gotten to the river when she heard pounding feet behind her.

chapter two

“Smartest man in Chicago”

Lucy stole a look over her shoulder to see how close Mackinac was.

But it was the big boy, with one hand gripping his trousers, followed by Bald Doris. The smaller boy was gaining on Lucy, his arms pumping with effort.

Mackinac had sent them to catch her. Lucy forced her feet to run faster.

The smaller boy pounded at her heels. “Wait! Hey!”

Get away! The words floated through Lucy’s head, then slipped back down her throat.

“We’re coming with you!” he shouted.

Lucy stopped, her throat burning. She bent over to catch her breath and got a good look at the bigger boy. His ears stuck out of hair that needed cutting, but his blue eyes were unafraid, as if running away were a natural thing to do, like a burp.

Bald Doris was right behind him, scratching her head. The matron had shaved her hair to get rid of lice, but the ointment they rubbed on her scalp made her itch.

The smaller boy had city in him. He was more like the kids Lucy knew back home in Chicago. He squinted at Lucy. “Where we going?”

Copyright © 2020 by Gennifer Choldenko. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.