Introduction

Every year in ancient Israel the high priest brought two goats into the Jerusalem temple on the Day of Atonement. He sacrificed one to expiate the sins of the community and then laid his hands on the other, transferring all the people’s misdeeds onto its head, and sent the sin-laden animal out of the city, literally placing the blame elsewhere. In this way, Moses explained, “the goat will bear all their faults away with it into a desert place.”1 In his classic study of religion and violence, René Girard argued that the scapegoat ritual defused rivalries among groups within the community.2 In a similar way, I believe, modern society has made a scapegoat of faith.

In the West the idea that religion is inherently violent is now taken for granted and seems self-evident. As one who speaks on religion, I constantly hear how cruel and aggressive it has been, a view that, eerily, is expressed in the same way almost every time: “Religion has been the cause of all the major wars in history.” I have heard this sentence recited like a mantra by American commentators and psychiatrists, London taxi drivers and Oxford academics. It is an odd remark. Obviously the two world wars were not fought on account of religion. When they discuss the reasons people go to war, military historians acknowledge that many interrelated social, material, and ideological factors are involved, one of the chief being competition for scarce resources. Experts on political violence or terrorism also insist that people commit atrocities for a complex range of reasons.3 Yet so indelible is the aggressive image of religious faith in our secular consciousness that we routinely load the violent sins of the twentieth century onto the back of “religion” and drive it out into the political wilderness.

Even those who admit that religion has not been responsible for all the violence and warfare of the human race still take its essential belligerence for granted. They claim that “monotheism” is especially intolerant and that once people believe that “God” is on their side, compromise becomes impossible. They cite the Crusades, the Inquisition, and the Wars of Religion of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. They also point to the recent spate of terrorism committed in the name of religion to prove that Islam is particularly aggressive. If I mention Buddhist non- violence, they retort that Buddhism is a secular philosophy, not a religion. Here we come to the heart of the problem. Buddhism is certainly not a religion as this word has been understood in the West since the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. But our modern Western conception of “religion” is idiosyncratic and eccentric. No other cultural tradition has anything like it, and even premodern European Christians would have found it reductive and alien. In fact, it complicates any attempt to pronounce on religion’s propensity to violence.

To complicate things still further, for about fifty years now it has been clear in the academy that there is no universal way to define religion.4 In the West we see “religion” as a coherent system of obligatory beliefs, institutions, and rituals, centering on a supernatural God, whose practice is essentially private and hermetically sealed off from all “secular” activities. But words in other languages that we translate as “religion” almost invariably refer to something larger, vaguer, and more encompassing. The Arabic din signifies an entire way of life. The Sanskrit dharma is also “a ‘total’ concept, untranslatable, which covers law, justice, morals, and social life.”5 The Oxford Classical Dictionary firmly states: “No word in either Greek or Latin corresponds to the English ‘religion’ or ‘religious.’”6 The idea of religion as an essentially personal and systematic pursuit was entirely absent from classical Greece, Japan, Egypt, Mesopotamia, Iran, China, and India.7 Nor does the Hebrew Bible have any abstract concept of religion; and the Talmudic rabbis would have found it impossible to express what they meant by faith in a single word or even in a formula, since the Talmud was expressly designed to bring the whole of human life into the ambit of the sacred.8

The origins of the Latin religio are obscure. It was not “a great objective something” but had imprecise connotations of obligation and taboo; to say that a cultic observance, a family propriety, or keeping an oath was religio for you meant that it was incumbent on you to do it. The word acquired an important new meaning among early Christian theologians: an attitude of reverence toward God and the universe as a whole. For Saint Augustine (c. 354–430 CE), religio was neither a system of rituals and doctrines nor a historical institutionalized tradition but a personal encounter with the transcendence that we call God as well as the bond that unites us to the divine and to one another. In medieval Europe, religio came to refer to the monastic life and distinguished the monk from the “secular” priest, someone who lived and worked in the world (saeculum).9

The only faith tradition that does fit the modern Western notion of religion as something codified and private is Protestant Christianity, which, like religion in this sense of the word, is also a product of the early modern period. At this time Europeans and Americans had begun to separate religion and politics, because they assumed, not altogether accurately, that the theological squabbles of the Reformation had been entirely responsible for the Thirty Years’ War. The conviction that religion must be rigorously excluded from political life has been called the charter myth of the sovereign nation-state.10 The philosophers and statesmen who pioneered this dogma believed that they were returning to a more satisfactory state of affairs that had existed before ambitious Catholic clerics had confused two utterly distinct realms. But in fact their secular ideology was as radical an innovation as the modern market economy that the West was concurrently devising. To non-Westerners, who had not been through this particular modernizing process, both these innovations would seem unnatural and even incomprehensible. The habit of separating religion and politics is now so routine in the West that it is difficult for us to appreciate how thoroughly the two co-inhered in the past. It was never simply a question of the state “using” religion; the two were indivisible. Dissociating them would have seemed like trying to ex- tract the gin from a cocktail.

In the premodern world, religion permeated all aspects of life. We shall see that a host of activities now considered mundane were experienced as deeply sacred: forest clearing, hunting, football matches, dice games, astronomy, farming, state building, tugs-of-war, town plan- ning, commerce, imbibing strong drink, and, most particularly, warfare. Ancient peoples would have found it impossible to see where “religion” ended and “politics” began. This was not because they were too stupid to understand the distinction but because they wanted to invest every- thing they did with ultimate value. We are meaning-seeking creatures and, unlike other animals, fall very easily into despair if we fail to make sense of our lives. We find the prospect of our inevitable extinction hard to bear. We are troubled by natural disasters and human cruelty and are acutely aware of our physical and psychological frailty. We find it astonishing that we are here at all and want to know why. We also have a great capacity for wonder. Ancient philosophies were entranced by the order of the cosmos; they marveled at the mysterious power that kept the heavenly bodies in their orbits and the seas within bounds and that ensured that the earth regularly came to life again after the dearth of winter, and they longed to participate in this richer and more permanent existence.

They expressed this yearning in terms of what is known as the perennial philosophy, so called because it was present, in some form, in most premodern cultures.11 Every single person, object, or experience was seen as a replica, a pale shadow, of a reality that was stronger and more enduring than anything in their ordinary experience but that they only glimpsed in visionary moments or in dreams. By ritually imitating what they understood to be the gestures and actions of their celestial alter egos—whether gods, ancestors, or culture heroes—premodern folk felt themselves to be caught up in their larger dimension of being. We humans are profoundly artificial and tend naturally toward archetypes and paradigms.12 We constantly strive to improve on nature or approximate to an ideal that transcends the day-to-day. Even our contemporary cult of celebrity can be understood as an expression of our reverence for and yearning to emulate models of “superhumanity.” Feeling ourselves connected to such extraordinary realities satisfies an essential craving. It touches us within, lifts us momentarily beyond ourselves, so that we seem to inhabit our humanity more fully than usual and feel in touch with the deeper currents of life. If we no longer find this experience in a church or temple, we seek it in art, a musical concert, sex, drugs— or warfare. What this last may have to do with these other moments of transport may not be so obvious, but it is one of the oldest triggers of ecstatic experience. To understand why, it will be helpful to consider the development of our neuroanatomy.

Each of us has not one but three brains that coexist uneasily. In the deepest recess of our gray matter we have an “old brain” that we inherited from the reptiles that struggled out of the primal slime 500 million years ago. Intent on their own survival, with absolutely no altruistic impulses, these creatures were solely motivated by mechanisms urging them to feed, fight, flee (when necessary), and reproduce. Those best equipped to compete mercilessly for food, ward off any threat, dominate territory, and seek safety naturally passed along their genes, so these self- centered impulses could only intensify.13 But sometime after mammals appeared, they evolved what neuroscientists call the limbic system, per- haps about 120 million years ago.14 Formed over the core brain derived from the reptiles, the limbic system motivated all sorts of new behaviors, including the protection and nurture of young as well as the formation of alliances with other individuals that were invaluable in the struggle to survive. And so, for the first time, sentient beings possessed the capacity to cherish and care for creatures other than themselves.15

Although these limbic emotions would never be as strong as the “me first” drives still issuing from our reptilian core, we humans have evolved a substantial hard-wiring for empathy for other creatures, and especially for our fellow humans. Eventually, the Chinese philosopher Mencius (c. 371–288 BCE) would insist that nobody was wholly without such sympathy. If a man sees a child teetering on the brink of a well, about to fall in, he would feel her predicament in his own body and would reflexively, without thought for himself, lunge forward to save her. There would be something radically wrong with anyone who could walk past such a scene without a flicker of disquiet. For most, these sentiments were essential, though, Mencius thought, somewhat subject to individual will. You could stamp on these shoots of benevolence just as you could cripple or deform yourself physically. On the other hand, if you cultivated them, they would acquire a strength and dynamism of their own.16

We cannot entirely understand Mencius’s argument without considering the third part of our brain. About twenty thousand years ago, during the Paleolithic Age, human beings evolved a “new brain,” the neocortex, home of the reasoning powers and self-awareness that enable us to stand back from the instinctive, primitive passions. Humans thus became roughly as they are today, subject to the conflicting impulses of their three distinct brains. Paleolithic men were proficient killers. Before the invention of agriculture, they were dependent on the slaughter of animals and used their big brains to develop a technology that enabled them to kill creatures much larger and more powerful than themselves. But their empathy may have made them uneasy. Or so we might conclude from modern hunting societies. Anthropologists observe that tribesmen feel acute anxiety about having to slay the beasts they consider their friends and patrons and try to assuage this distress by ritual purification. In the Kalahari Desert, where wood is scarce, bushmen are forced to rely on light weapons that can only graze the skin. So they anoint their arrows with a poison that kills the animal—only very slowly. Out of ineffable solidarity, the hunter stays with his dying victim, crying when it cries, and participating symbolically in its death throes. Other tribes don animal costumes or smear the kill’s blood and excrement on cavern walls, ceremonially returning the creature to the underworld from which it came.17

Paleolithic hunters may have had a similar understanding.18 The cave paintings in northern Spain and southwestern France are among the earliest extant documents of our species. These decorated caves almost certainly had a liturgical function, so from the very beginning art and ritual were inseparable. Our neocortex makes us intensely aware of the tragedy and perplexity of our existence, and in art, as in some forms of religious expression, we find a means of letting go and encouraging the softer, limbic emotions to predominate. The frescoes and engravings in the labyrinth of Lascaux in the Dordogne, the earliest of which are seventeen thousand years old, still evoke awe in visitors. In their numinous depiction of the animals, the artists have captured the hunters’ essential ambivalence. Intent as they were to acquire food, their ferocity was tempered by respectful sympathy for the beasts they were obliged to kill, whose blood and fat they mixed with their paints. Ritual and art helped hunters express their empathy with and reverence (religio) for their fellow creatures—just as Mencius would describe some seventeen millennia later—and helped them live with their need to kill them.

In Lascaux there are no pictures of the reindeer that featured so largely in the diet of these hunters.19 But not far away, in Montastruc, a small sculpture has been found, carved from a mammoth tusk in about 11,000 BCE, at about the same time as the later Lascaux paintings. Now lodged in the British Museum, it depicts two swimming reindeer.20 The artist must have watched his prey intently as they swam across lakes and rivers in search of new pastures, making themselves particularly vulnerable to the hunters. He also felt a tenderness toward his victims, conveying the unmistakable poignancy of their facial expressions without a hint of sentimentality. As Neil MacGregor, director of the British Museum, has noted, the anatomical accuracy of this sculpture shows that it “was clearly made not just with the knowledge of a hunter but also with the insight of a butcher, someone who had not only looked at his animals but had cut them up.” Rowan Williams, the former archbishop of Canterbury, has also reflected insightfully on the “huge and imaginative generosity” of these Paleolithic artists: “In the art of this period, you see human beings trying to enter fully into the flow of life, so that they become part of the whole process of animal life that’s going on all around them . . . and this is actually a very religious impulse.”21 From the first, then, one of the major preoccupations of both religion and art (the two being inseparable) was to cultivate a sense of community—with nature, the animal world, and our fellow humans.

We would never wholly forget our hunter-gatherer past, which was the longest period in human history. Everything that we think of as most human—our brains, bodies, faces, speech, emotions, and thoughts— bears the stamp of this heritage.22 Some of the rituals and myths devised by our prehistoric ancestors appear to have survived in the practices of later, literate cultures. In this way, animal sacrifice, the central rite of nearly every ancient society, preserved prehistoric hunting ceremonies and the honor accorded the beast that gave its life for the community.23 Much of what we now call “religion” was originally rooted in an acknowledgment of the tragic fact that life depended on the destruction of other creatures; rituals were addressed to helping human beings face up to this insoluble dilemma. Despite their real respect, reverence, and even affection for their prey, however, ancient huntsmen remained dedicated killers. Millennia of fighting large aggressive animals meant that these hunting parties became tightly bonded teams that were the seeds of our modern armies, ready to risk everything for the common good and to protect their fellows in moments of danger.24 And there was one more conflicting emotion to be reconciled: they probably loved the excitement and intensity of the hunt.

Here again the limbic system comes into play. The prospect of killing may stir our empathy, but in the very acts of hunting, raiding, and battling, this same seat of emotions is awash in serotonin, the neurotransmitter responsible for the sensation of ecstasy that we associate with some forms of spiritual experience. So it happened that these violent pursuits came to be perceived as sacred activities, however bizarre that may seem to our understanding of religion. People, especially men, experienced a strong bond with their fellow warriors, a heady feeling of altruism at putting their lives at risk for others and of being more fully alive. This response to violence persists in our nature. The New York Times war correspondent Chris Hedges has aptly described war as “a force that gives us meaning”:

War makes the world understandable, a black and white tableau of them and us. It suspends thought, especially self-critical thought. All bow before the supreme effort. We are one. Most of us willingly accept war as long as we can fold it into a belief system that paints the ensuing suffering as necessary for a higher good, for human beings seek not only happiness but meaning. And tragically war is some- times the most powerful way in human society to achieve meaning.25

It may be too that as they give free rein to the aggressive impulses from the deepest region of their brains, warriors feel in tune with the most elemental and inexorable dynamics of existence, those of life and death. Put another way, war is a means of surrender to reptilian ruthlessness, one of the strongest of human drives, without being troubled by the self- critical nudges of the neocortex.

The warrior, therefore, experiences in battle the transcendence that others find in ritual, sometimes to pathological effect. Psychiatrists who treat war veterans for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have noted that in the destruction of other people, soldiers can experience a self- affirmation that is almost erotic. Yet afterward, as they struggle to disentangle their emotions of pity and ruthlessness, PTSD sufferers may find themselves unable to function as coherent human beings. One Vietnam veteran described a photograph of himself holding two severed heads by the hair; the war, he said, was “hell,” a place where “crazy was natural” and everything “out of control,” but, he concluded:

The worst thing I can say about myself is that while I was there I was so alive. I loved it the way you can like an adrenaline high, the way you can love your friends, your tight buddies. So unreal and the realest thing that ever happened. . . . And maybe the worst thing for me now is living in peacetime without a possibility of that high again. I

hate what that high was about but I loved that high.26

“Only when we are in the midst of conflict does the shallowness and vapidness of much of our lives become apparent,” Hedges explains. “Trivia dominates our conversation and increasingly our airwaves. And war is an enticing elixir. It gives us a resolve, a cause. It allows us to be noble.”27 One of the many, intertwined motives driving men to the battlefield has been the tedium and pointlessness of ordinary domestic existence. The same hunger for intensity would compel others to become monks and ascetics.

The warrior in battle may feel connected with the cosmos, but after- ward he cannot always resolve these inner contradictions. It is fairly well established that there is a strong taboo against killing our own kind—an evolutionary stratagem that helped our species to survive.28 Still, we fight. But to bring ourselves to do so, we envelop the effort in a mythology—often a “religious” mythology—that puts distance between us and the enemy. We exaggerate his differences, be they racial, religious, or ideological. We develop narratives to convince ourselves that he is not really human but monstrous, the antithesis of order and goodness. Today we may tell ourselves that we are fighting for God and country or that a particular war is “just” or “legal.” But this encouragement doesn’t always take hold. During the Second World War, for instance, Brigadier General S. L. A. Marshall of the U.S. Army and a team of historians interviewed thousands of soldiers from more than four hundred infantry companies that had seen close combat in Europe and the Pacific. Their findings were startling: only 15 to 20 percent of infantrymen had been able to fire at the enemy directly; the rest tried to avoid it and had developed complex methods of misfiring or reloading their weapons so as to escape detection.29

It is hard to overcome one’s nature. To become efficient soldiers, recruits must go through a grueling initiation, not unlike what monks or yogins undergo, to subdue their emotions. As the cultural historian Joanna Bourke explains the process:

Individuals had to be broken down to be rebuilt into efficient fighting men. The basic tenets included depersonalization, uniforms, lack of privacy, forced social relationships, tight schedules, lack of sleep, disorientation followed by rites of reorganization according to military codes, arbitrary rules, and strict punishment. The methods of brutalization were similar to those carried out by regimes where men were taught to torture prisoners.30

So, we might say, the soldier has to become as inhuman as the “enemy” he has created in his mind. Indeed, we shall find that in some cultures, even (or perhaps especially) those that glorify warfare, the warrior is somehow tainted, polluted, and an object of fear—both an heroic figure and a necessary evil, to be dreaded, set apart.

Our relationship to warfare is therefore complex, possibly because it is a relatively recent human development. Hunter-gatherers could not afford the organized violence that we call war, because warfare requires large armies, sustained leadership, and economic resources that were far beyond their reach.31 Archaeologists have found mass graves from this period that suggest some kind of massacre,32 yet there is little evidence that early humans regularly fought one another.33 But human life changed forever in about 9000 BCE, when pioneering farmers in the Levant learned to grow and store wild grain. They produced harvests that were able to support larger populations than ever before and eventually they grew more food than they needed.34 As a result, the human population increased so dramatically that in some regions a return to hunter-gatherer life became impossible. Between about 8500 BCE and the first century of the Common Era—a remarkably short period given the four million years of our history—all around the world, quite independently, the great majority of humans made the transition to agrarian life. And with agriculture came civilization; and with civilization, warfare.

In our industrialized societies, we often look back to the agrarian age with nostalgia, imagining that people lived more wholesomely then, close to the land and in harmony with nature. Initially, however, agriculture was experienced as traumatic. These early settlements were vulnerable to wild swings in productivity that could wipe out the entire population, and their mythology describes the first farmers fighting a desperate battle against sterility, drought, and famine.35 For the first time, backbreaking drudgery became a fact of human life. Skeletal remains show that plant- fed humans were a head shorter than meat-eating hunters, prone to anemia, infectious diseases, rotten teeth, and bone disorders.36 The earth was revered as the Mother Goddess and her fecundity experienced as an epiphany; she was called Ishtar in Mesopotamia, Demeter in Greece, Isis in Egypt, and Anat in Syria. Yet she was not a comforting presence but extremely violent. The Earth Mother regularly dismembered con- sorts and enemies alike—just as corn was ground to powder and grapes crushed to unrecognizable pulp. Farming implements were depicted as weapons that wounded the earth, so farming plots became fields of blood. When Anat slew Mot, god of sterility, she cut him in two with a ritual sickle, winnowed him in a sieve, ground him in a mill, and scattered his scraps of bleeding flesh over the fields. After she slaughtered the enemies of Baal, god of life-giving rain, she adorned herself with rouge and henna, made a necklace of the hands and heads of her victims, and waded knee-deep in blood to attend the triumphal banquet.37

These violent myths reflected the political realities of agrarian life. By the beginning of the ninth millennium BCE, the settlement in the oasis of Jericho in the Jordan valley had a population of three thousand people, which would have been impossible before the advent of agriculture. Jericho was a fortified stronghold protected by a massive wall that must have consumed tens of thousands of hours of manpower to construct.38 In this arid region, Jericho’s ample food stores would have been a magnet for hungry nomads. Intensified agriculture, therefore, created conditions that that could endanger everyone in this wealthy colony and transform its arable land into fields of blood. Jericho was unusual, however—a portent of the future. Warfare would not become endemic in the region for another five thousand years, but it was already a possibility, and from the first, it seems, large-scale organized violence was linked not with religion but with organized theft.39

Agriculture had also introduced another type of aggression: an institutional or structural violence in which a society compels people to live in such wretchedness and subjection that they are unable to better their lot. This systemic oppression has been described as possibly “the most subtle form of violence,”40 and, according to the World Council of Churches, it is present whenever “resources and powers are unequally distributed, concentrated in the hands of the few, who do not use them to achieve the possible self-realization of all members, but use parts of them for self-satisfaction or for purposes of dominance, oppression, and control of other societies or of the underprivileged in the same society.”41 Agrarian civilization made this systemic violence a reality for the first time in human history.

Paleolithic communities had probably been egalitarian because hunter-gatherers could not support a privileged class that did not share the hardship and danger of the hunt.42 Because these small communities lived at near-subsistence level and produced no economic surplus, inequity of wealth was impossible. The tribe could survive only if everybody shared what food they had. Government by coercion was not feasible because all able-bodied males had exactly the same weapons and fighting skills. Anthropologists have noted that modern hunter-gatherer societies are classless, that their economy is “a sort of communism,” and that people are honored for skills and qualities, such as generosity, kindness, and even-temperedness, that benefit the community as a whole.43 But in societies that produce more than they need, it is possible for a small group to exploit this surplus for its own enrichment, gain a monopoly of violence, and dominate the rest of the population.

As we shall see in Part One, this systemic violence would prevail in all agrarian civilizations. In the empires of the Middle East, China, India, and Europe, which were economically dependent on agriculture, a small elite, comprising not more than 2 percent of the population, with the help of a small band of retainers, systematically robbed the masses of the produce they had grown in order to support their aristocratic life- style. Yet, social historians argue, without this iniquitous arrangement, human beings would probably never have advanced beyond subsistence level, because it created a nobility with the leisure to develop the civilized arts and sciences that made progress possible. All premodern civilizations adopted this oppressive system; there seemed to be no alternative. This inevitably had implications for religion, which permeated all human activities, including state building and government. Indeed, we shall see that premodern politics was inseparable from religion. And if a ruling elite adopted an ethical tradition, such as Buddhism, Christianity, or Islam, the aristocratic clergy usually adapted their ideology so that it could support the structural violence of the state.44

In Parts One and Two we shall explore this dilemma. Established by force and maintained by military aggression, warfare was essential to the agrarian state. When land and the peasants who farmed it were the chief sources of wealth, territorial conquest was the only way such a kingdom could increase its revenues. Warfare was, therefore, indispensable to any premodern economy. The ruling class had to maintain its control of the peasant villages, defend its arable land against aggressors, conquer more land, and ruthlessly suppress any hint of insubordination. A key figure in this story will be the Indian emperor Ashoka (c. 268–232 BCE). Appalled by the suffering his army had inflicted on a rebellious city, he tirelessly promoted an ethic of compassion and tolerance but could not in the end disband his army. No state can survive without its soldiers. And once states grew and warfare had become a fact of human life, an even greater force—the military might of empire—often seemed the only way to keep the peace.

So necessary to the rise of states and ultimately empires is military force that historians regard militarism as a mark of civilization. With- out disciplined, obedient, and law-abiding armies, human society, it is claimed, would probably have remained at a primitive level or have degenerated into ceaselessly warring hordes.45 But like our inner conflict between violent and compassionate impulses, the incoherence between peaceful ends and violent means would remain unresolved. Ashoka’s dilemma is the dilemma of civilization itself. And into this tug-of-war religion would enter too. Since all premodern state ideology was inseparable from religion, warfare inevitably acquired a sacral element. Indeed, every major faith tradition has tracked that political entity in which it arose; none has become a “world religion” without the patronage of a militarily powerful empire, and, therefore, each would have to develop an imperial ideology.46 But to what degree did religion contribute to the violence of the states with which it was inextricably linked? How much blame for the history of human violence can we ascribe to religion itself? The answer is not as simple as much of our popular discourse would suggest.

___

Our world is dangerously polarized at a time when humanity is more closely interconnected—politically, economically, and electronically— than ever before. If we are to meet the challenge of our time and create a global society where all peoples can live together in peace and mutual respect, we need to assess our situation accurately. We cannot afford oversimplified assumptions about the nature of religion or its role in the world. What the American scholar William T. Cavanaugh calls “the myth of religious violence”47 served Western people well at an early stage of their modernization, but in our global village we need a more nuanced view in order to understand our predicament fully.

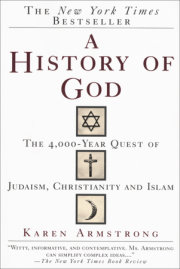

This book focuses mainly on the Abrahamic traditions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam because they are the ones most in the spotlight at the moment. Yet because there is such a widespread conviction that monotheism, the belief in a single God, is especially prone to violence and intolerance, the first section of the book will examine it in com- parative perspective. In traditions preceding the Abrahamic faiths, we will see not only how military force and an ideology imbued with the sacred were both essential to the state but also how from earliest times there were those who agonized about the dilemma of necessary violence and proposed “religious” ways to counter aggressive urges and channel them toward more compassionate ends.

Time would fail me were I to attempt to cover all instances of religiously articulated violence, but we will explore some of the most prominent in the long history of the three Abrahamic religions, such as Joshua’s holy wars, the call to jihad, the Crusades, the Inquisition, and the European Wars of Religion. It will become clear that when premodern people engaged in politics, they thought in religious terms and that faith permeated their struggle to make sense of the world in a way that seems strange to us today. But that is not the whole story. To paraphrase a British commercial: “The weather does lots of different things—and so does religion.” In religious history, the struggle for peace has been just as important as the holy war. Religious people have found all kinds of ingenious methods of dealing with the assertive machismo of the reptilian brain, curbing violence, and building respectful, life-enhancing communities. But as with Ashoka, who came up against the systemic militancy of the state, they could not radically change their societies; the most they could do was propose a different path to demonstrate kinder and more empathic ways for people to live together.

When we come to the modern period, in Part Three, we will, of course, explore the wave of violence claiming religious justification that erupted during the 1980s and culminated in the atrocity of September 11, 2001. But we will also examine the nature of secularism, which, despite its manifold benefits, has not always offered a wholly irenic alternative to a religious state ideology. The early modern philosophies that tried to pacify Europe after the Thirty Years’ War in fact had a ruthless streak of their own, particularly when dealing with casualties of secular modernity who found it alienating rather than empowering and liberating. This is because secularism did not so much displace religion as create new religious enthusiasms. So ingrained is our desire for ultimate meaning that our secular institutions, most especially the nation-state, almost immediately acquired a “religious” aura, though they have been less adept than the ancient mythologies at helping people face up to the grimmer realities of human existence for which there are no easy answers. Yet secularism has by no means been the end of the story. In some societies attempting to find their way to modernity, it has succeeded only in damaging religion and wounding psyches of people unprepared to be wrenched from ways of living and understanding that had always supported them. Lick- ing its wounds in the desert, the scapegoat, with its festering resentment, has rebounded on the city that drove it out.

Notes

introduction

1. Leviticus 16:21–22. Unless otherwise stated, all biblical quotations—in both the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament—are from The Jerusalem Bible (London, 1966).

2. René Girard, Violence and the Sacred, trans. Patrick Gregory (Baltimore, 1977), p. 251.

3. Stanislav Andreski, Military Organization in Society (Berkeley, LosAngeles, and London, 1968); Robert L. O’Connell, Ride of the Second Horseman: The Birth and Death of War (New York and Oxford, 1995), pp. 6–13, 106–10, 128–29; O’Connell, Of Arms and Men: A History of War, Weapons and Aggression (New York and Oxford, 1989), pp. 22–25; John Keegan, A History of Warfare (London and New York, 1993), pp. 223–29; Bruce Lincoln, “War and Warriors: An Overview,” in Death, War, and Sacrifice: Stud- ies in Ideology and Practice (Chicago and London, 1991), pp. 138–40; Johan Huizinga, Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play Element in Culture (Boston, 1955 ed.), pp. 89–104; Mark Juergensmeyer, Terror in the Mind of God: The Global Rise of Religious Violence (Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London, 2001), p. 90; Malise Ruthven, A Fury for God: The Islamist Attack on America (London, 2002), p. 101; James A. Aho, Religious Mythology and the Art of War: Comparative Religious Symbolisms of Military Violence (Westport, CT, 1981), pp. xi–xiii, 4–35; Richard English, Terrorism: How to Respond (Oxford and New York, 2009), pp. 27–55.

4. Thomas A. Idinopulos and Brian C.Wilson, eds., What Is Religion? Origins, Definitions, and Explanations (Leiden, 1998); Wilfred Cantwell Smith, The Meaning and End of Religion: A New Approach to the Religious Traditions of Mankind (New York, 1962); Talal Asad, “The Construction of Religion as an Anthropological Category,” in Genealogies of Religion: Discipline and Reasons of Power in Christianity and Islam (Baltimore and London, 1993); Derek Peterson and Darren Walhof, eds., The Invention of Religion: Rethinking Belief in Politics and History (New Brunswick, NJ, and London, 2002); Timothy Fitzgerald, ed., Religion and the Secular: Historical and Colonial Formations (London and Oakville, CT, 2007); Arthur L. Greil and David G. Bromley, eds., Defining Religion: Investigating the Boundaries Between the Sacred and Secular (Oxford, 2003); Daniel Dubuisson, The Western Construction of Religion: Myths, Knowledge and Ideology, trans. William Sayers (Baltimore, 2003); William T. Cavanaugh, The Myth of Religious Violence (Oxford, 2009).

5. Dubuisson, Western Construction of Religion, p. 168.

6. H.J.Rose, “Religion, Terms Relating to,”inM.Carey,ed., The Oxford Classical Dictionary (Oxford, 1949).

7. Smith, Meaning and End of Religion, pp. 50–68.

8. Louis Jacobs, ed., The Jewish Religion: A Companion (Oxford, 1995), p. 418.

9. Smith, Meaning and End of Religion, pp. 23–25, 29–31, 33.

10. Cavanaugh, Myth of Religious Violence, pp. 72–85.

11. Mircea Eliade, The Myth of Eternal Return, or, Cosmos and History, trans. Willard R. Trask (Princeton, NJ, 1991), pp. 1–34.

12. Ibid., pp. 32–34; Karl Jaspers, The Origin and Goal of History, trans. Michael

Bullock (London, 1953), p. 40.

13. Paul Gilbert, The Compassionate Mind: A New Approach to Life’s Challenges

(London, 2009).

14. P. Broca, “Anatomie comparée des circonvolutions cérébrales: le grand lobe lim-

bique,” Revue d’anthropologie 1 (1868).

15. Gilbert, Compassionate Mind, pp. 170–71.

16. Mencius, The Book of Mencius, 2A:6.

17. Walter Burkert, Homo Necans: The Anthropology of Greek Sacrificial Ritual,

trans. Peter Bing (Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London, 1983), pp. 16–22.

18. Mircea Eliade,A History of Religious Ideas, trans. Willard R. Trask, 3 vols.(Chicago and London, 1978, 1982, 1985), 1:7–8, 24; Joseph Campbell, Historical Atlas of World Mythologies, 2 vols. (New York, 1988), 1:48–49; Joseph Campbell with Bill Moyers, The Power of Myth (New York, 1988), pp. 70–72, 85–87.

19. André LeRoi-Gourhan, Treasures of Prehistoric Art, trans. Norbert Guterman

(New York, 1967), p. 112.

20. Jill Cook, The Swimming Reindeer (London, 2010).

21. Neil MacGregor, A History of the Word in 100 Objects (London and New York,

2001), pp. 22, 24.

22. J. Ortega y Gasset, Meditations on Hunting (New York, 1985), p. 3.

23. Walter Burkert, Structure and History in Greek Mythology and Ritual(Berkeley,

Los Angeles, and London, 1980), pp. 54–56; Burkert, Homo Necans, pp. 42–45.

24. O’Connell, Ride of Second Horseman, p. 33.

25. Chris Hedges, War Is a Force That Gives Us Meaning (New York, 2003), p. 10.

26. Theodore Nadelson, Trained to Kill: Soldiers at War (Baltimore, 2005), pp. 64,

68–69.

27. Hedges, War Is a Force, p. 3.

28. Irenöus Eibl-Eibesfeldt, Human Ethology (New York, 1989), p. 405.

29. Lt. Col. Dave Grossman, On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill

in War and Society, rev. ed. (New York, 2009), pp. 3–4.

30. Joanna Bourke, An Intimate History of Killing: Face to Face Killing in Twentieth-

Century Warfare (New York, 1999), p. 67.

31. Peter Jay, Road to Riches, or The Wealth of Man (London, 2000), pp. 35–36.

32. K. J. Wenke, Patterns of Prehistory: Humankind’s First Three Million Years

(New York, 1961), p. 130; Keegan, History of Warfare, pp. 120–21; O’Connell, Ride of Second Horseman, p. 35.

33. M. H. Fried, The Evolution of Political Society: An Essay in Political Anthropology (New York, 1967), pp. 101–2; Clark McCauley, “Conference Overview,” in Jonathan Haas, ed., The Anthropology of War (Cambridge, UK, 1990), p. 11.

34. Gerhard E. Lenski, Power and Privilege: A Theory of Social Stratification (Chapel Hill, NC, and London, 1966), pp. 189–90.

35. O’Connell, Ride of Second Horseman, pp. 57–58.

36. J. L. Angel, “Paleoecology, Pleodeography and Health,” in S. Polgar, ed., Population, Ecology, and Social Evolution (The Hague, 1975); David Rindos, The Origins of Agriculture: An Evolutionary Perspective (Orlando, FL, 1984), pp. 186–87.

37. E. O. James, The Ancient Gods: The History and Diffusion of Religion in the Ancient Near East and the Eastern Mediterranean (London, 1960), p. 89; S. H. Hooke, Middle Eastern Mythology: From the Assyrians to the Hebrews (Harmondsworth, UK, 1963), p. 83.

38. Kathleen Kenyon, Digging Up Jericho: The Results of the Jericho Excavations, 1953–1956 (New York, 1957).

39. Jacob Bronowski, The Ascent of Man(Boston,1973),pp.86–88;JamesMellaart, “Early Urban Communities in the Near East, 9000 to 3400 BCE,” in P. R. S. Moorey, ed., The Origins of Civilisation (Oxford, 1979), pp. 22–25; P. Dorell, “The Uniqueness of Jericho,” in P. R. S. Moorey and P. J. Parr, eds., Archaeology in the Levant: Essays for Kathleen Kenyon (Warminster, UK, 1978).

40. Robert Eisen, The Peace and Violence of Judaism: From the Bible to Modern Zionism (Oxford, 2011), p. 12.

41. World Council of Churches, Violence, Nonviolence and the Struggle for Social Justice (Geneva, 1972), p. 6.

42. Lenski, Power and Privilege, pp. 105–14; O’Connell, Ride of Second Horseman, p. 28; E. O. Wilson, On Human Nature (Cambridge, MA, 1978), p. 140; Margaret Ehrenberg, Women in Prehistory (London, 1989), p. 38.

43. A. R. Radcliffe, The Andaman Islanders (New York, 1948), pp. 43, 177.

44. John H. Kautsky, The Politics of Aristocratic Empires, 2nd ed. (New Brunswick, NJ, and London, 1997), pp. 374, 177.

45. Keegan, History of Warfare, pp. 384–86; John Haldon, Warfare, State and Society in the Byzantine World, 565–1204 (London and New York, 2005), pp. 10–11.

46. Bruce Lincoln, “The Role of Religion in Achaemenian Imperialism,” in Nicole Brisch, ed., Religion and Power: Divine Kingship in the Ancient World and Beyond (Chicago, 2008).

47. Cavanaugh, Myth of Religious Violence.

Copyright © 2014 by Karen Armstrong. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.