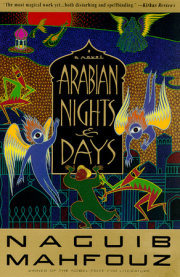

1.

The court gathered in its divine entirety within the Hall of Justice, whose high walls were adorned with writing in the sacred hieroglyphic script, under a gilded ceiling in whose heavens gleamed the dreams of all humankind. In the center of the hall Osiris reposed on his golden throne; to his right was Isis, and to his left Horus, each seated on their own thrones. Not far from Osiris’s feet squatted Thoth, Scribe of the Gods, the Book of All laid open across his thighs. Meanwhile, chairs plated with pure gold were arrayed on both sides of the hall, ready to receive those whose ultimate fates now would be written.

To commence the proceedings, Osiris declaimed, “From the remotest past, it has been decreed that humans shall spend their lives on earth. All the while, there would go with them, even over the threshold of death—like a shadow that clings to them—a record of all their acts and desires, embodied on their naked forms. Finally, there would be held a detailed dialog that would end with a decisive word. This, then, is that trial, convened after the passage of the allotted span of time.”

Osiris then signaled to Horus, and the youth called out with a booming voice, “King Menes!”

From the door at the farthest end of the hall, a man entered, attired in his burial shroud, though his head and feet were bare. With clear features and a powerful form, he drew closer and closer to Osiris’s throne, until he stood three arms’ lengths from it, in a stance of stark humility.

At this, Osiris beckoned to the divine scribe Thoth, who began to read from the book before him, “The mightiest monarch of the First Dynasty, he warred on the Libyans until he subdued them. He attacked Lower Egypt, joining it to southern Egypt, declaring himself king of all Egypt together, crowning himself with the Double Crown. He altered the course of the Nile, establishing the city of Memphis on the new land this formed.”

Addressing Menes, Osiris demanded, “Tell us what you have to say.”

“Thoth, your sacred scribbler, has condensed my life in words,” Menes replied. “How easy is the telling, and how hard was the doing!”

“We have our own view of how to appraise rulers and their deeds,” Osiris warned him. “Do not waste time by praising yourself.”

“I inherited rule of the southern kingdom from my family,” Menes said. “With it I inherited a mighty dream—which all of our early men and women shared—to cleanse the country of foreign intruders, and establish an eternal unity whose two wings would be the lands of southern and northern Egypt.

“The voice of my paternal aunt, Awuz, was the prime moving force that ignited this awesome dream. She would gaze at me with concern and say, ‘Will you spend your whole life eating, drinking, and hunting?’ Or she would goad me by adding, ‘Osiris did not teach us farming merely to give us a chance to fight among ourselves over the water needed to irrigate a feddan.’

“Once I said to my beloved spouse that I could feel a firebrand in my breast that would not cool until I had realized this dream. She was a splendid royal wife when she answered me with passion, ‘Don’t let the Libyans threaten your capital—and don’t allow the people to divide up the land that the Nile has made one.’

“So I threw myself with vigor into training our strong men for battle, praying to the gods to endow me with the satisfaction of victory, until at my hand the vision of which my pioneering parents and grandparents had dreamed was fulfilled.”

“You reaped one hundred thousand of the Libyans’ lives,” Osiris reproached him.

“They were the aggressors, My Lord,” said Menes in his own defense.

“And of the Egyptians, northerners and southerners combined, two hundred thousand fell as well,” Osiris reminded him.

“They sacrificed themselves for the sake of our nation’s unity,” said Menes. “Then security and peace reigned over all, while the blood that had regularly been shed in periodic fighting ceased to flow into the waters of the Nile.”

“Could you not win the people over with words before resorting to the sword?” asked Osiris.

“I tried that with my neighbors, and brought some of them to us without going to war,” Menes answered. “But afterward, the sword achieved in a few years what words had failed to do in generations.”

“Many say such things merely to conceal their belief in force,” said Osiris.

“The glory and security of Egypt took possession of my emotions,” objected Menes.

“Your personal glory too,” the presiding divinity rejoined.

“I do not deny that,” Menes conceded, “but well-being was general throughout the country.”

“Wherein your own dynasty and supporters benefited the most—and the peasants the least,” continued Osiris.

“I spent most of my reign in combat and construction,” Menes replied. “I never luxuriated in the life of the palace, nor savored the taste of fine food or drink, nor cavorted with women other than my own wife—while I was obliged to reward my helpers as befitted their labors.”

Isis asked leave to speak.

“My Lord,” she said, “you are judging a human, not a god. According to this man, he forsook ease and indolence to purge the land of invaders. He unified Egypt, freed her hidden powers, and uncovered her buried blessings. At the same time, he provided the peasants with peace and security. He is a son of which to be proud.”

Osiris was silent briefly, then called out, “O King, take the first seat at the right side of the throne as your own.”

Menes proceeded to his chair, knowing he was one of the privileged few who may dwell in the Other World.

Copyright © 2012 by Naguib Mahfouz. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.