Chapter 1

Shootout in Miami

It was nine forty-five a.m. on April 11, 1986, when Special Agents Benjamin Grogan and Gerald Dove spotted the two suspects driving a stolen black Chevrolet Monte Carlo on South Dixie Highway. The pair had been robbing banks and armored trucks in southern Dade County over the past four months. To catch them, Gordon McNeill, a supervisory special agent with the Miami field office of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, had set up a rolling stakeout. “They had killed two people; another woman was missing,” McNeill said. “They had shot another guy four times. In my twenty-one years with the agency, I never felt more sure that when we found these guys, they would go down hard.”

Moments later, other FBI units converged; soon, three unmarked sedans trailed the bank robbers. McNeill, closing from the opposite direction, spotted the black Monte Carlo at the head of the strange convoy. In the passenger seat, one suspect shoved a twenty-round magazine into a Ruger Mini-14 semiautomatic rifle. “Felony car stop!” McNeill shouted into his radio to the other units. “Let’s do it!”

FBI vehicles corralled the Monte Carlo, ramming the fugitive automobile and forcing it into a large driveway. The three remaining government sedans skidded into surrounding positions. Two more FBI cars arrived across the street. In all, eight agents faced the two suspects.

Suddenly, one of the fugitives started shooting. FBI men scrambled for cover and returned fire. The occupants of the Monte Carlo seemed to be hit in the fusillade, but the government rounds weren’t stopping them.

In the chaos, the federal agents struggled to reload their revolvers, jamming cartridges one after another into five- and six-shot Smith & Wessons. Three of the FBI agents were members of a special-tactics squad and carried fifteen-round S&W pistols. But none of the handgun fire seemed to slow the criminals. The gunman with the Ruger Mini-14 merely had to snap a new magazine into his rifle to have another twenty rounds instantly. One of his mags had forty rounds. His partner had a twelve-gauge shotgun with extended eight-round capacity. The bank robbers were armed for a small war.

Agent McNeill took a round in his right hand, shattering bone. Shredded flesh jammed the cylinder of his revolver, making it impossible to reload. He rose from a crouch to reach for a shotgun on the backseat of an FBI vehicle. As he did, a .223 rifle round pierced his neck. He fell, paralyzed. A fellow agent was severely wounded when he paused to reload his Smith & Wesson Chief’s Special. “Everybody went down fighting,” McNeill said. “We just ran into two kamikazes.”

As law enforcement officials would later discover, the bank robbers, Michael Platt and William Matix, were no ordinary thugs. They had met in the 1970s at Fort Campbell, Kentucky. Matix served as a military policeman with the 101st Airborne. Platt received Special Forces training. Both were practiced marksmen. They operated a landscaping business and according to neighbors seemed like hardworking individuals. Neither one had a criminal record. But something had turned them into psychopaths.

Platt, demonstrating his deadly close-combat skills, worked the shoulder-fired Mini-14 with precision. Based on the M14 military rifle, the Mini-14 was popular with small-game hunters, target shooters, and, ironically, the police. Platt took full advantage of the semiautomatic weapon’s large magazine and penetrating ammunition. Bobbing and weaving, he sneaked up on Grogan and Dove, the agents who had originally spotted the black Monte Carlo. “He’s coming behind you!” another agent screamed. But the warning came too late. Platt fatally shot Grogan in the torso and Dove in the head.

The firefight had been going on for four minutes when Agent Edmundo Mireles, badly wounded, staggered toward Platt and Matix, who had piled into a bullet-ridden FBI Buick. A civilian witness described Mireles’s stiff-legged gait as “stone walking.” Holding a Smith & Wesson .357 Magnum at arm’s length, he fired repeatedly at the two gunmen at point-blank range, killing them both. It was the bloodiest day in FBI history.

All told, the combatants fired 140 rounds. In addition to the deaths of Platt and Matix, two FBI agents were killed, three were permanently crippled, and two others were injured. gun battle “looked like ok corral,” the Palm Beach Post declared the next morning, quoting a shaken witness. But the legendary gunfight in 1881 in Tombstone, Arizona, had lasted only thirty seconds and involved just thirty shots, leaving three dead—one fewer than the modern-day battle in Miami.

///

Lieutenant John H. Rutherford, the firing-range director with the Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office, heard about the shootout later that day. “The bad guys,” he recalled, “were starting to carry high-capacity weapons, unlike what they had carried in the past. . . . That was a scary, terrible thing to hear about,” he said. “If the FBI is outgunned, something is wrong.”

Scholars of law enforcement and small arms pored over the forensic records of the Miami Shootout, generating thousands of pages of reports. Police departments across the country held seminars on the gun battle. Gun magazines published dramatic reconstructions. NBC broadcast a made-for-TV movie called In the Line of Fire: The FBI Murders.

Later examination would reveal that, for all their bravery, the FBI agents prepared poorly for the violent encounter. At the time, though, and ever since, one idea about the significance of Miami eclipsed all others. The lawmen had been, in Lieutenant Rutherford’s word, “outgunned.” It was a perception widely shared by cops, politicians, and law-abiding firearm owners: The criminals were better armed than the forces of order. Nationwide, crime rates were rising. Drug gangs ruled inner-city neighborhoods. Guns had replaced knives in the hands of violent teenagers. The police, the FBI, and all who protected the peace were increasingly seen as being at a lethal disadvantage. The FBI helped shape this perception by emphasizing the seven revolvers its agents had used, deflecting attention from the three fifteen-round pistols and two twelve-gauge shotguns they also brought to the fight.

“Although the revolver served the FBI well for several decades, it became quite evident that major changes were critical to the well-being of our agents and American citizens,” FBI Director William Sessions said in an agency bulletin after Miami. Revolvers held too little ammunition, and they were too difficult to reload in the heat of a gunfight. There were questions about their “stopping power”: In Miami, the FBI fired some seventy rounds, and Platt and Matix received a total of eighteen bullet wounds. Yet the killers stayed alive long enough to inflict a terrible toll.

In 1987, Jacksonville’s Lieutenant Rutherford received the formal assignment to recommend a new handgun to replace the Smith & Wesson revolvers that his department issued. His counterparts in hundreds of local, state, and federal police agencies were given similar missions. “My job,” Rutherford told me, “was to find a better gun.”

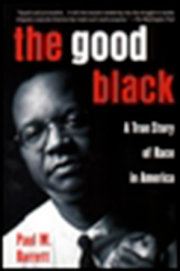

Copyright © 2012 by Paul M. Barrett. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.