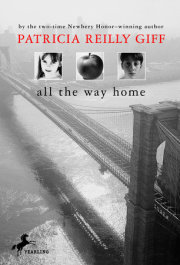

1

Sudden light burst against the foal's closed eyes. She needed to open them, and to get on her legs, which trembled under her. It was the only thing she knew, that struggle to stand.

And a feeling of warmth, the smell of warmth.

She opened her eyes and heaved herself up under that dark shape. Its head turned toward her, a soft muzzle, a nicker of sound.

Milk. Rich and hot.

She could see almost in a full circle. Another creature was nearby, its smell unpleasant, but she turned back to the mare.

When she was filled with milk, she leaned against the mare; she felt the swish of the mare's long tail against her face. She opened her mouth and felt the hair with her tongue.

Safe.

2

My bedroom seemed bare without the horse pictures. Small holes from the thumbtacks zigzagged up and down the walls.

Tio Paulo would have a fit when he saw them.

Never mind Tio Paulo. I tucked the pictures carefully into my backpack. "You're going straight to America with me," I told them.

Everything was packed now, everything ready. I was more than ready, too, wearing stiff new jeans, a coral shirt--my favorite color--and a banana clip that held back my bundle of hair. My outfit had taken almost all the dinheiro I'd saved for my entire life.

"You look perfectly lovely," I said to myself in the mirror, then shook my head. "English, Lidie. Speak English." I started over. "You look very--" What was that miserable word anyway? Niece?

Who could think with Tio Paulo downstairs in the kitchen, pacing back and forth, calling up every two minutes, "You're going to miss the plane!"

I took a last look around at the peach bedspread, the striped curtains Titia Luisa and I had made, the books on the shelf under the window. But I had no time to think about it; there was something I wanted to do before I left.

I rushed downstairs, tiptoeing along the hall, past Tio Paulo in the kitchen, and stepping over Gato, the calico cat who was dozing in the doorway.

Out back, the field was covered with thorny flowers the color of tea, and high grass that whipped against my legs as I ran. I was late. Too bad for Tio Paulo. He'd have to drive more than his usual ten miles an hour.

I whistled, and Cavalo, the farmer's bay horse, whinnied. He trotted toward me, then stopped, waiting. I climbed to the top of the fence and cupped my fingers around his silky brown ears before I threw myself on his back.

"Go." I pressed my heels into his broad sides and held on to his thick mane.

Last time.

We thundered down the cow path, stirring up dust. My banana clip came off, and my hair, let loose, was as thick as the forelocks on Cavalo's forehead.

We reached the blue house where we'd lived when Mamae was alive. I didn't have to pull on Cavalo's mane; he knew enough to stop.

The four of us had been there together: Mamae, my older brother, Rafael; my father; and me. And it was almost as if Mamae were still there in the high bed in her room, linking her thin fingers with mine. The three of you will still belong together, Lidie, you'll make it a family.

Shaking my head until my hair whipped into my face, I had held up my fingers: There are four of us, Mamae. Four.

I remembered her faint smile. Ai, only seven years old, but still you're just like your father, the Horseman.

Just like Pai.

Two weeks later, Mamae was gone, flown up to the clouds to watch over us from heaven, Titia Luisa said. And Pai and Rafael went off to America, leaving me with Titia Luisa and Tio Paulo. I still felt that flash of anger when I thought of their leaving without me.

I ran my fingers through Cavalo's mane. I'm going now, Mamae. Pai has begun to race horses at a farm in America, and there's room for me at last. Pai and Rafael have a house!

"Goodbye, blue house." The sound of my voice was loud in my ears. "Goodbye, dear Mamae."

Tio Paulo was outside in the truck now, blasting the horn for me.

"Pay no attention to him," I whispered to Cavalo.

Cavalo felt the pressure of my knees and my hands pulling gently on his mane, and turned.

We crossed the muddy rio, my feet raised away from the splashes of water, and climbed the slippery rocks, Cavalo's heels clanking against the stone.

In the distance, between his yelling and the horn blaring, Tio Paulo sounded desperate.

Suddenly I was feeling that desperation, too. We had to go all the way to Sao Paulo to catch the plane. But I was determined. Five minutes, no more. "Hurry," I told Cavalo.

Up ahead was the curved white fence that surrounded the lemon grove. The overhanging branches were old and gnarled, the leaves a little dusty, and the lemons still green.

Pai, my father, had held me up the day he'd left. His hair was dark, his teeth straight and white. "Pick a lemon for me, Lidie. I'll take it to America."

I'd reached up and up and pulled at the largest lemon I could find.

"When I send for you, you'll bring me another," he'd said.

What else was in that memory? Their suitcases on the porch steps, and I was sobbing, begging, "Take me, take me."

He'd scooped me up, my face crushed against his shirt, and his voice was choked. "This is the worst of all of it," he'd said. In back of him, Luisa was crying, and Tio banged his fist against the porch post.

But that was the last time I cried. After they left, I promised myself I'd never shed one more tear. Not for anyone.

Copyright © 2011 by Patricia Reilly Giff. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.