1

Father's foot swung back and forth, tick, tock, tick, tock, in time with the clock on the wall. It was nearly ten o'clock at night. Tuesday, September 13, 1901. We were assembled in the parlor of the main lodge of the Tahawus Club, a resort in the Adirondack Mountains in upper New York state. Usually I would have been asleep already, but not that night. We were waiting for a telegram.

Father stared hard at the page of the book he was reading, almost hard enough to make the words pop off the page. I half expected them to--Father could do anything--but I knew better.

He turned the page. He turned another. Page after page, so fast I knew he wasn't really reading, though Father read faster than anyone I knew, faster even than Mother, who read all the time. Father did everything fast.

He hated waiting. We all did.

Mother looked up from her own book. She said, "Wouldn't you feel better if--"

"Not hardly!" Father snapped. "I'm not going until I'm sent for. Been there once already. I'd be like an old vulture, hovering over him. Dreadful."

Normally Father wouldn't cut Mother off like that, and she wouldn't stand for it if he did. But that night Father smacked another page of his book and Mother just shook her head. "His poor wife," she murmured. "What on earth will she do?"

I didn't ask whom she meant. I knew. I might have been only ten years old, but I paid attention to everything. Mrs. McKinley, the president's wife, was an invalid. At state dinners the president had to sit beside her, instead of across the table the way he was supposed to, so that if she had an epileptic fit he could cover her face with his napkin. At the inaugural ball, my big sister, Alice, sat on the arm of Mrs. McKinley's chair without ever noticing that Mrs. McKinley was sitting in it. Afterward Sister told Mother that she hadn't meant to be rude.

I didn't get to go to the ball, but I did meet Mrs. McKinley at the inauguration, before the swearing in. She was so lifeless and still, she reminded me of one of Quentin's wax dolls. President McKinley was kind but not joyful. Sister said he had the personality of a mackerel. "Next to him," she said, "Father's brighter than the sun."

Next to most people Father was brighter than the sun. So was Sister, for that matter.

I had wondered if Mrs. McKinley would talk more when she wasn't surrounded by crowds. I had wondered if she would invite Mother to tea in the fall; maybe I could go too. Now I guessed not. A week before, President McKinley had been shot in the stomach while attending the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York. At first everyone had thought he was going to recover, but now it looked as if they were wrong.

Quentin, my littlest brother, who ought to have been in bed two hours before, climbed onto Father's knee. "Are you an old vulture?" he shouted. "Or are you a bear?"

Quentin was only three. He didn't understand. Father played bear with Quentin and Archie, and sometimes with Kermit and me, almost every night. Not that night, though. Archie, who was seven, looked up from the parlor rug with grave anxiety. Archie did understand.

"I'll take him, sir." Mame, our ancient Irish nurse, rose from the sofa and held out her arms. Quentin ducked and tried to bury himself beneath Father's elbow. Father wrapped his arms around Quentin.

"He can stay," Mother said softly. "Just for tonight, Mame. If you're tired, go ahead to bed. I'll take care of the children." Mame hesitated, but her back had been hurting all day. She went out of the parlor. I could hear her steps down the hall, and the front door opening and shutting. The cabin we were staying in was just across from the main lodge.

Quentin fell asleep. Father adjusted his spectacles, moved Quentin more securely into the crook of his arm, and shut his book. His crossed foot still swung in the air. Tick, tock.

Archie reenacted the battle of Kettle Hill with his tin soldiers on the rug. The rest of us sprawled across the sofas and chairs. We were taking up the entire parlor, and I hoped none of the other guests minded. We'd come to the Adirondacks for two weeks of vaction after Archie caught chicken pox, Quentin stuck a mothball up his nose, Sister got an abscess in her jaw, Ted got bronchitis, Quentin got an ear infection, I got poison ivy, and Mother almost had a breakdown. Father had been away much of the summer giving speeches, but he'd joined us three days before. The day before, Kermit and I had hiked with him halfway up Mount Marcy and stayed overnight in a hunting cabin. In the morning it was raining, and the first telegram came, saying that McKinley was worse.

"Why haven't the other guests come into the parlor?" I asked.

"They could if they wished to," Mother said.

"Respect," my oldest brother, Ted, said. "Privacy."

"They weren't worried about privacy before," I said. On the first day Father got here, all the guests and staff lined up to shake his hand. He told them the story of the cougar he killed on his last hunting trip to the Badlands, and they applauded. It was a good story, but I thought they would have applauded a bad one too. Everywhere we went, people wanted to talk to Father.

Kermit, who was almost twelve, put down his book of poetry and looked at me.

"What?" I said.

"Think," he said.

I frowned. "Does everyone here know why we're waiting?"

"I imagine so," he said.

I pursed my lips at him. Sometimes Kermit had too much imagination.

"Nonsense," muttered Father.

"Yes," Mother murmured. "Yes, Ethel. They do."

Ted's face twitched. This was his fourteenth birthday, a fact that had gotten lost after the morning's news even though we'd tried to celebrate it at dinner. Ted was Father's namesake, a hard thing to be. None of us could match Father, but I knew Ted felt obliged to try.

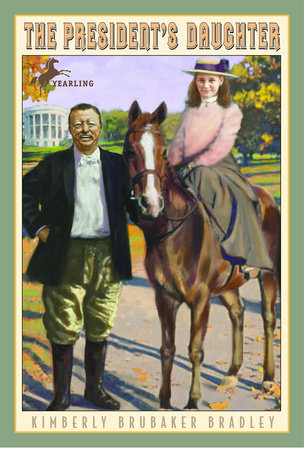

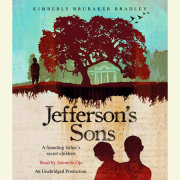

Copyright © 2004 by Kimberly Brubaker Bradley. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.