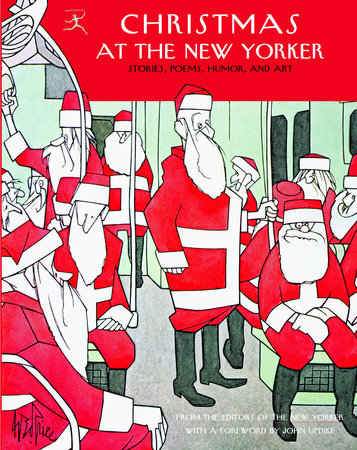

MORE OF A SURPRISE

SALLY BENSON

Just after Thanksgiving Day every year, Jim and Rhoda Huston made out their Christmas lists. The lists were for each other and were nicely balanced, combining a feeling for the practical with Yuletide abandon. For instance, one of the items on Mrs. Huston’s list might be “Pigskin gloves—size 6½,” a good, sensible suggestion, but it would be followed by a bit of frivolity, such as “Bath salts—something spicy.”

Some years ago, Mr. Huston had made the grave mistake of picking out things from Rhoda’s list that he thought she really needed and he had lived to regret it. It was the Christmas she had dutifully supplied the three pairs of pajamas, no buttons, that he had asked for but had also added six boxes of tobacco from Dunhill’s so that he could blend his own pipe mixture. Since then she had hammered away at the idea that while it was lovely to get the presents one needed, it was even lovelier to be surprised with some foolish little thing. Jim Huston tried to explain that if Christmas presents were to be surprises, there wasn’t much use in their making out lists, but he couldn’t get Rhoda to understand. “I’d rather be surprised than anything,” she told him. “And it’s a perfectly simple thing to be able to do to anybody. Just let yourself go.”

This year, the advertising firm Jim Huston worked for gave all its employees a bonus, and when his bonus check was sent in to him early in December and he saw that it was for six hundred dollars, he was going to telephone Rhoda right away about it when a thought struck him, and he decided that he would spend the whole amount on one staggering Christmas present for her. He took the list she had made for him out of his pocket and read it. She had written, “Set of dishes—service for four—Altman’s—$5.95—plenty good enough. Barbizon slips—peach—size 36. Lipstick—your choice. Bath towels—like the ones we have. A scarf—something gay. 6 small glasses—the kind for tomato juice. Heart-shaped sachet—smallest size. Bath soap—luxurious. Bridge-table cover—maroon. Breakfast tray, if not too much—I long for one. Sweater—pullover—better get size 38, as apt to run small.”

He looked at the bonus check and, taking Rhoda’s list he tore it into fine pieces. Then he rang for Miss Thompson, his secretary, told her that he would not be back at the office until three, and, putting on his hat and coat, started out. For a while he wandered up Fifth Avenue, stopping to stare at the displays in the store windows. It was the sight of a fur coat in Gunther’s window that made him realize that he had heard Rhoda complain about her nutria coat, which she had worn every winter for the last ten years, and he walked bravely in. An hour later, somewhat staggered at the price of furs, he paid most of his bonus check for a soft, pretty squirrel coat.

“I’ll pick it up the Saturday before Christmas,” he told the salesgirl. “I don’t want it delivered. It’s a surprise.”

“And a wonderful one,” she said.

His face lit up and he began to smile. “I just had an idea,” he said. “You haven’t an old fur of some sort around here, have you? I mean, it would be pretty funny if I got an old piece of fur, something like an old neckpiece, and had that wrapped up, wouldn’t it? Then she’d think that’s what she was getting and then I’d spring the coat on her later. I mean, fool her, sort of.”

“I see,” the girl said. “I’m afraid we haven’t anything. You might try a thrift shop. They have second-hand furs.”

When Jim went back to his office, he carried with him a slightly worn white rabbit-fur square, for which he had paid fifteen dollars. He showed it to Miss Thompson, explaining the joke to her and laughing uproariously. “And I want you,” he said, “to wrap it up. Do a job on it. Make it look like something. You know, something I’d taken pains about.”

He smiled every time he thought about it the rest of the afternoon, and when he went home that night, he was ready for the buildup. He assumed a gloomy air, and, during dinner, he mentioned the fact that the bonus he’d sort of counted on hadn’t materialized. “We’re not getting one,” he said.

“Isn’t that mean!” Rhoda said.”

He sighed. “Worse than that,” he said. “I was counting on it for your Christmas. I’ve bought a lot more War Bonds than I could afford. You’ll have a pretty slim Christmas, I’m afraid.”

“Oh, that’s all right,” Rhoda said. “Of course, I always sort of save ahead for your Christmas. I always know what I have to spend ahead of time.”

“That’s what I should have done,” he said contritely.

“The things on my list won’t amount to much,” Rhoda said.

“I was going to surprise you this year, though,” he said.

“And I’m sure you will,” she said brightly.

In the days that followed, Rhoda was more than helpful with small, extra suggestions. She told Jim that nothing made her feel as gay as a pretty plant on Christmas Day—a colorful one. She mentioned the fact that small, Shocking-pink makeup cases could be had for as little as one dollar. She had seen, she said, some enchanting ashtrays, trimmed with gold dots, that were seventy-four cents. “I don’t know when I’ve run across so many darling little things, things I’d never think of buying for myself, and for practically nothing, if a person takes the time to shop for them,” she said.

Every time she mentioned Christmas, Jim let himself appear to be sunk in gloom. As the holiday approached, she began to watch him to see if he brought in any packages when he came home at night, and she made a great point of telling him to keep out of the hall closet, where she had hidden the few things she had bought for him. On the Saturday before Christmas, he brought the fur coat home and left it with the superintendent of the building, who promised to keep it in a safe place. Jim then went happily up to his apartment, carrying the white rabbitfur square, which was wrapped magnificently.

He set the package down on the hall table and kissed Rhoda, who pretended that she hadn’t even noticed that he had a package. And later in the evening, she said, “Do you know, darling, that I was just sitting here wishing that I hadn’t bought you just a lot of stuff. I was wishing I’d just put all my efforts on one thing. Something you really wanted. I think we’ve always made a mistake in getting too many small things and never anything really important.”

Jim thought he could never keep his face straight.

Christmas Eve, Rhoda carried six packages from the hall closet and arranged them under the tree with the presents from his family and hers. Jim took the elegant parcel that Miss Thompson had wrapped and, sighing, laid it with the others. “Doesn’t look like much, does it?” he asked.

“Darling,” she answered, “I’m sure it’s lovely.”

That night Rhoda couldn’t go to sleep. She lay awake in the dark trying to imagine what Jim had bought her. It was not jewelry, she decided, because it was too big. She found it hard to convince herself that if Jim had bought her only one thing, it must be something really handsome. For one thing, he didn’t act as though he were satisfied with it himself, and, thinking about him, she reached over and touched him protectively on the shoulder.

Copyright © 2009 by The New Yorker. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.