"All this," said Wayne the plumber, "was written down in the Bible five thousand years ago." He was out on the deck, taking a break from doing angioplasty on the pipes beneath my kitchen sink. Meanwhile, he was giving his assistant, John Pickles, a lesson.

"Hey, Wayne," I yelled from an upstairs window, "you're wrong about the date. Most of the events in the Bible didn't even take place five thousand years ago. Solomon, for example, in all his glory, at best got going about three thousand years ago, and nobody wrote the diary of his activities until at least a century later."

I shouldn't have gotten involved. But why not? I was desperate to get in on a theological discussion, especially with Wayne. Wayne was a plumber all right, but he was also a missionary in Ecuador. He returned to the States one year out of every five and ran the roads from North Carolina to Boston, replacing and repairing the broken and burst pipes of the bourgeoisie. After that it was back to church in the poor places outside Quito, where conversion was his calling.

"Be that as it may," Wayne shouted back, "I'd have to see some evidence."

Ah, evidence! I hadn't been subscribing to Biblical Archaeological Review for nothing--although it was almost nothing given the generous terms of their initial subscription rate. But evidence is a paltry thing compared to passion, and this, I knew, was where Wayne would have me by the U bolt.

It, and by it I mean my desperation, had begun quietly enough on a soft summer day in the first year of the new millennium c.e. (I'm being careful here). The traffic on Route 9 outside the Chestnut Hill Mall congested and fumed, but the SUV in front of me presented a hopeful bumper sticker very much in favor of Jesus. It had been a long time since I had really thought about Jesus. In all likelihood, in the way of my people in the few but noisy and concentrated places that we occupied in the vast world, I had never given him a fair shake.

So I shook. In the historical, evidentiary direction, of course. It turned out, discovered on my excursion to the Newton Public Library section 801.3, that Jesus wasn't just Jewish, he was really Jewish. Not only did he have no idea he was a Christian; he never imagined that he might become one. In addition, if I could work up the courage, I had some news to break to Wayne, and it was earth-shattering. According to the two most eminent professors of Jewish Jesus, "son of God" was an Aramaic figure of speech. Digest that! It meant nothing more and nothing less than "pious dude." It wasn't at all uncommon on the dusty streets outside Jerusalem for young studs to greet one another in the swish tongue of the day, with a friendly "Hey, son of God, how you doing?"

Now, I had known for some time how dangerous inspired language could be to the literal-minded. For example, my own lot, the Jews. Who told us to strap a little black box with a prayer inside onto our heads once a day? Answer: no one. "And ye shall bind these words upon your forehead" clearly meant "remember them." But no, a hundred years pass and someone dreams up the apparatus. Soon enough he's got a business going, and the leather guy is happy, so who wants to interfere with at least two men's livelihoods?

I was trying not to interfere with Wayne's, but there was no turning back. After a quick refresher read-up in The Changing Face of Jesus by Gezer Vermes, pages 12 to 25, I went down into the kitchen.

"OK," I said, "how do you explain this? The Book of John says that the Last Supper took place on the day before the Passover Seder, but the Synoptic Gospels--that's Matthew, Mark, and Luke..."

"Yes, I know what they are," Wayne said. He was patient with me.

"Well, they date it on the day of the Seder. You see what I'm saying. They can't both be right."

Wayne had his head under the sink. His legs were sticking out.

"John--" He was trying hard to project his voice, but I lost the rest of his sentence.

"It's impossible, you see," I continued, "that the Jews could have held a court hearing the following day, on Passover itself. That was against the rules. So John must have got it wrong."

Wayne slid his pear-shaped body out from under the sink. His blond hair was flattened. He looked a little like Yogi Bear.

"'The rules'? 'Impossible'?"

"Yes."

"Well, didn't you ever hear of rules being broken?"

He had a point there. I had to admit that it was really hard to know what had gone down between pink dawn and rosy dusk on consecutive days two thousand years ago. I'd probably have to go back to the library.

"All I know," Wayne said, "is that we could do with someone like Jesus now."

He stood up. He was a head taller than I was, and he had a wrench in his hand.

I decided to leave the "son of God" issue until after he'd fixed the pipes.

Wayne dropped the wrench into his toolbox. "Are you," he asked, "by any chance a connoisseur of the ancient languages?"

"I know a little Italian," I replied.

"The Hebrew aleph," he went on, "is a pictorial symbol of the shift from a hunting to an agrarian culture. The letter is made up of a bull's horns and a broken ring. The taming of the bull, you see. There is a bull in a paddock not far from my house in the village of Pifo who has a brass ring in his nose. I call him Aleph."

"That's fascinating," I said. "So you don't believe that Hebrew is a holy tongue."

"I believe in the holy tongue of fire that is Our Lord Jesus Christ."

"When do you think you'll be done with the sink?" I asked.

"This job," Wayne said, "is quite complicated. It looks as if someone has been shoving Q-tips and rice down the waste disposal. It could take all day to unblock."

It was dinnertime. My wife, Claire, and I were eating noodles ordered in from Jamjuti, our local Thai place. My son, Nick, had his own hamster food, three lettuce leaves and a crouton. He was starving himself in order to make weight for his first varsity high school wrestling match.

"Did you know," I began, "that the aleph is a pictorial symbol..."

"Wayne been round again?" my wife interrupted. "I thought he was back in Ecuador."

"Next month. He returns next month."

"Maybe you should go with him."

She had been harsh with me for two days--since she had overheard me on the phone telling a friend that I was in love with Helen Hunt. At the time she'd gotten off a scathing "Yeah, like she's gonna call you." I thought that was the end of the matter, but it turned out to be just the beginning.

My son looked up from his leaves.

"Temptation Island tonight," he said.

"Disgusting," my wife responded. "You're just like your father. And don't you watch anything other than Fox?"

"Yes," he replied, "I watch Cribs and sometimes there's stuff on the WB."

I was thinking hard about the historical Jesus, but as I'd already bombed with the aleph I didn't want to broach the subject in conversation.

The festival of Hannukah was approaching, with its lovely candle lights not to be used for utilitarian purposes. I could have mentioned this at the dinner table, but that was to risk sounding like a religious fanatic, when in fact I was merely a sentimentalist and eclectic reader with too much time on his hands. Wrestling seemed safe.

"What weight are you going at?" I asked Nick.

"One seventy."

"And what do you weigh now?"

"One seventy-five."

He had the crouton speared on the end of his fork.

"Don't you think," he said, "that your friend Paul Vogel looks exactly like Osama bin Laden?"

It was true, but Paul Vogel also looked like Kobe Bryant and Scottie Pippen. And a little kid in New York City had once approached him on a bus and asked if he was Jesus.

I reminded everybody of this, and then I ate the shrimp out of the pad Thai while avoiding the noodles.

"According to the most unimpeachable sources," I ventured, "Jesus was probably a Galilean Hasid, a pious wanderer, a miracle worker from out of the cold north."

There was silence in the room. Only the fridge muttered something in reply, buzzed up, probably, by my Nordic reference.

Eventually Claire said: "I'm sure it's hot in the Galilee, most of the time, anyway."

I'd expected this blow to fall, but anticipation didn't help to reduce its impact. These were serious times, and there was no excuse at all for flights of fancy in the service of a decent sentence.

"Are you going to come and watch?" Nick asked.

"When's the meet?"

"Wednesday night."

"I'll be there," I said.

It wasn't as if I had anything else to do. I was recuperating from a laparoscopy performed one week earlier to remove my rebellious gallbladder, which had decided to swell to the bursting point and then spit tiny stones into the narrow channel that rushed deliveries to my liver, creating a blockage that not even Wayne could have foreseen.

The phone rang.

"You get it," my wife said.

It was Paul Vogel calling from San Francisco.

"Hey," I said, "we were just talking about you. The uncanny resemblance."

"Tell me about it," he replied. "I can't go out of the house. Half the neighborhood thinks I want to blow up the Golden Gate Bridge."

"Did you think about shaving off your beard?"

"What are you, the Taliban? This is a free country. You can micromanage your own facial hair."

"You're right," I said. "That's the beauty of America."

We talked for a while about my scar, which was less a scar than four little holes deftly drilled by Dr. Pamela Gevertz, who was thirty and a newlywed.

"They pulled the gangrenous gallbladder out through my navel," I said.

"Helen might like to know that," my wife put in without looking up from her plate.

The crowd around the wrestling mat was standing room only. The bout in progress offered an uncontroversial intergender affair, for these are open prairie days in the wide United States such as the world has never known. A boy in the 190-pound range had spread his arms to circle the girth of his female twin. As the view cleared before me he threw her to the ground and began to twist her arm. Somehow, Atlas rose, lifted her rival up on her back, and shunted him all the way to the perimeter. "Good job, Teresa!" the man next to me shouted. He was wearing a T-shirt that had the words Hombres de Acero printed above the yellow and black logo of the Pittsburgh Steelers. Teresa's parents, her teammates, their parents, and all the women in the audience from our side cheered wildly. The wrestlers untangled, returned to the middle of the circle, and began to grab at each other again.

"It's like watching a marriage, isn't it?" said a skinny dad on my left whom I knew to be a recent divorce.

"Or Jacob wrestling with the angel," I responded, but my interlocutor pretended that he hadn't heard me and I looked away as if I hadn't spoken.

OK, so it wasn't only Jesus. Thoughts on religious matters were leeching onto my brain at an appalling rate, and this had been the case ever since my early dismissal from the hospital on the dual grounds of my body's good behavior and pressure from managed care.

I lie. The trouble had begun even earlier, in the brown, unhappy hour before surgery. There I was, half asleep in the arms of Morpheus, when my long-dead father stretched out his arm and clapped a silky yarmulke onto the back of my head. I was deeply grateful--glad, in a worst-case scenario--to meet my maker in the proper attire. Ten minutes later I was less appreciative when Norma, my still-living mother-in-law, showed up in the doorway of my hospital room. "'Go in with a smile, come out with a smile,' that's what my Aunt Dixie used to say," she said. Five milligrams of morphine performed the work that twenty years of therapy had failed to accomplish: "Go away," I replied.

Back on the mat, Teresa had pinned her man; his glistening hands flapped like fish on the hook and then went quiet: general uproar, the upspring of solid Teresa, slower rise of defeated opponent, quickly followed by a civilized handshake. It is finished. O strapping 190-pound women of America, we who are about to die salute you!

Next up was Nick, whose opponent held him in a headlock for what felt like an hour. How much neck twisting can a boy take? I looked away. Hombre de Acero was making his way toward the exit. The relentless gym lights shone on his bald spot, or perhaps the light emanated from his head. I couldn't tell. When I looked back Nick's noggin was still on his shoulders and he was lifting one of his opponent's legs in such a way that the boy was forced to hop backwards before crashing to the ground.

The ground. The muddy ground, so different from heaven with its whizzing planets, icy comets, and coldhearted angels. We were watching the New England Patriots fight for a playoff spot. The TV, suicidally beautiful, was lit with the glow of fading December. Miami lined up. There was a minute to go.

"Don't worry," Nick said. "No team ever retrieves its own onside kick."

"Jesus Christ," I yelled. "Now you've jinxed them."

"No," he said, "you jinxed them in the third quarter when you forgot to turn the mini-helmet the way we were going."

The kick bounced up and Fred Coleman hugged the ball. He sustained an enormous hit but didn't let go.

"Double jinx," I said joyously. "It's like two minuses making a plus."

It was almost impossible to rid oneself of superstition, much harder than to break with God, whose behavior over the centuries had been truly unfathomable (what was He thinking?), and now, on account of 9/11, the entire nation was crossing its fingers every time it crossed the street. That was an irony, of course, that even Wayne might have appreciated. The fundamentalists had returned us to fundamentals.

"It's mainly Christian, you know," I said to Nick.

"What is?"

The Patriots were hugging and smacking each other all over the field.

"Our superstitions: unlucky thirteen, the apostles at the Last Supper; touch wood, fingering a piece of the cross; don't walk under a ladder, the shadow thrown by Jesus bearing the cross."

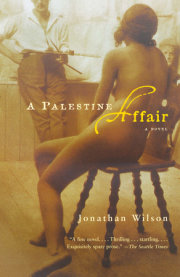

Copyright © 2005 by Jonathan Wilson. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.