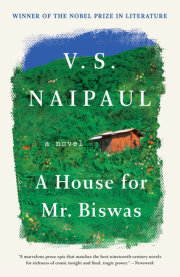

INTRODUCTIONThe task of introducing this extraordinary and moving correspondence is a delicate one. In these letters between a father and a son, the older man worn down by the cares of a large family and the distress of unfulfilled ambitions, the younger on the threshold of a broad and brilliant literary career, lies some of the raw material of one of the finest and most enduring novels of the twentieth century: V. S. Naipaul's

A House for Mr Biswas. Yet the letters also celebrate Seepersad Naipaul's achievement as a writer, not merely in the genesis and evolution of his single published novel,

The Adventures of Gurudeva; but also, and perhaps more strikingly, in revealing the dedication of the true artist. For Seepersad Naipaul (Pa), the life of the mind -- the writer's life -- was everything: to record the ways of men and women, with a shrewd, comical and kindly eye, and to do that from within his own originality, was to live nobly. In his elder son, Vidia, he found a miraculous echo to this belief -- miraculous, because there is no sense of a son's following in his father's footsteps, or of a father's urging that he might do so. There is a sense, rather, of the two men's being in step, neither embarrassed by any of the implications of the generation that divided them -- and Vidia only seventeen when the present correspondence opens. The difference in their ages, and the fact of Seepersad's early death, have allowed Vidia to acknowledge the debt he owes to his father, and he has embraced the opportunity to do so in manifold ways in his work. In this correspondence, the reader will recognize the subtle, and unwitting, repayment of a father's debt to his son. . . .

GILLON AITKENLettersSeptember 21, 1949 -- September 22, 1950: Port of Spain to OxfordTrinidad

September 21, 1949

Dear Kamla [Naipaul's elder sister],

I wonder what is the matter with this typewriter. It looks all right now, though. I am enclosing some cuttings which, I am sure, will delight you. You will note that I went after all to the Old Boys' Association Dinner. I can count those hours as among the most painful I have ever spent. In the first place, I have no table manners; in the second, I had no food. Special arrangements, I was informed after the dinner, had been made for me, but these appeared to have been limited to serving me potatoes in various ways -- now fried, now boiled. I had told the manager to bring me some corn soup instead of the turtle soup that the others were having. He ignored this and the waiter brought up to me a plateful of a green slime. This was the turtle soup. I was nauseated and annoyed and told the man to take it away. This, I was told, was a gross breach of etiquette. So I had bread and butter and ice-cold water for the first two eating rounds. The menu was in French. What you would call stewed chicken they called 'Poulet Sauté Renaissance'. Coffee was 'moka'. I had rather expected that to be some exotic Russian dish. Dessert included something called 'Pomme Surprise'. This literally means 'surprised apple', and the younger Hannays, who was next to me, told me it was an apple pudding done in a surprise manner. The thing came. I ate it. It was fine. But I tasted no apple. 'That,' Hannays told me, 'is the surprise.'

I have just finished filling out the application forms for entrance to the University; I had some pictures of myself taken. I had always thought that, though not attractive, I was not ugly. This picture undeceived me. I never knew my face was fat. The picture said so. I looked at the Asiatic on the paper and thought that an Indian from India could look no more Indian than I did. My face would give anyone the idea that I was a two-hundred-pounder. I had hoped to send up a striking intellectual pose to the University people, but look what they have got. And I even paid two dollars for a re-touched picture.

I am all right. I am actually reading once more. I decided to start preparing myself for next year by a thorough knowledge of the nineteenth-century novel. I read the Butler book [Samuel Butler's

The Way of All Flesh (1903)]; I think it is not half as good as Maugham's

Of Human Bondage. The construction is clumsy. Butler has stressed too much on passing religious conflicts; is too concerned with proving his theory of heredity. I then went on to Jane Austen. I had read so much in praise of her. I went to the library and got

Emma. It has an introduction by Monica Dickens, which extolled the book as the finest Austen ever wrote. Frankly, the introduction proved better reading than the book itself. Jane Austen appears to be essentially a writer for women; if she had lived in our age she would undoubtedly have been a leading contributor to the women's papers. Her work really bored me. It is mere gossip. It could appeal to a female audience. The diction is fine, of course. But the work, besides being mere gossip, is slick and professional.

I think you would be interested to know how my $75 will be spent. I have taken over all your debts. $50 will go to the bank; $10 to Millington; and $15 to Dass. I have about two dollars pocket money. I get this from Mamie for teaching Sita. Sending that child to school to get an academic education is a waste of time and money. She is the most obtuse thing I have ever met. If you want to break a man's heart, give him a class of Sitas to teach. I wonder if you know that I have been teaching George. He is dull but could pass if made to work hard. I am sure you will be glad to know that Jainarayan is making splendid progress. Those people are a sorry lot. This devaluation business is going to make it even harder for them.

It is not for us at home to do extensive writing; that is your job. It is you who are seeing new countries, having new and exciting experiences which will probably remain in your memory as the most interesting part of your life. I must say, however, that your letters have improved enormously. I wonder why. Is it because you are writing spontaneously, without any conscious effort at literature? I think it is. . . .

. . . While you are in India, you should keep your eyes open. This has two meanings: the subsidiary one is to watch your personal effects carefully; the Indians are a thieving lot. Remember what happened to the trousers of the West Indian cricket eleven. [The white flannel trousers of the West Indian cricket team visiting India at this time were famously stolen in Bombay.] Keep your eyes open and let me know whether Beverly Nichols is right. He went to India in 1945, and saw a wretched country, full of pompous mediocrity, with no future. He saw the filth; refused to mention the 'spiritualness' that impresses another kind of visitor. Of course the Indians did not like the book, but I think he was telling the truth. From Nehru's autobiography, I think the Premier of India is a first-class showman using his saintliness as a weapon of rule. But I am sure it has a certain basis in fact. Huxley may have degenerated of late into an invalid crippled by a malady that has received enormous approval by the intellectuals -- mysticism -- but what he said in his book [

Jesting Pilate (1926)] about India twenty years or so ago is true. He said that it was half-diets that produced ascetics and people who spend all their time in meditation. You will be right at the heart of the whole cranky thing. Please don't get contaminated; I will be glad when your three years will be finished; then you could breathe the invigorating air of atheism. (I don't like that word. It seems to suggest that the person is interested in religion; it doesn't suggest one who ignores it completely . . .)

I suppose that by now you have received the ten pounds. We got your diary. I could sense an underlying unhappiness and worry in it. I don't think you were completely happy. I could imagine how glad you were when you saw Boysie at Avonmouth. After all, who could be perfectly happy going to a strange land with only about seventy dollars to stay heaven knows how long? I doubt whether we could have stood the financial strain. I am very glad how things turned out.

I will write shortly. Goodbye and good luck.

With affection,

Vido [an intimate form of Vidia (itself a diminutive of Vidiadhar), the name by which V. S. Naipaul was and is familiarly known]

[To Kamla]

Trinidad

October 10, 1949

My dear little fool,

You are the damnedest ass. Your letter amused me as I read the first few lines; then it became grotesque.

You are a silly stupid female, after all. I fancy you rather enjoyed writing that plea to a wayward brother. It made you a hero a la Hollywood. Listen, my dear 'very pretty' Miss Naipaul, you are free to indulge your fancy, and let it roam, but don't ever mix me up in it. I appreciate that the picture of an intelligent, sensitive ('he is the most sensitive of all your children') brother flinging himself at the dogs, as it were, eating out his heart, and drowning his sorrows in drink, at the departure of a dear sister is appealing and not without its melodramatic flavour.

You were the same over here. Do you remember your taunts at my getting a job? You enjoyed the picture you built up, the picture someone would form of me if he knew nothing of the family. A weak, bespectacled brother is frustrated by his lack of physical attraction. It grows on him, for he is intellectual, and he becomes a drunkard. He is easily led astray; when he falls for vices, he falls hard. The sister knew it all the time. She weeps as a fountain as she pens the bitter letter to her brother, inquiring if what she hears is true, half hoping to hear that it is. You are a fool. He is easily led astray. Living in a family where generosity is bad business; where mediocrity and stupidity hold sway; where meat-eating is a virtue -- he is ungenerous, he is stupid, he eats meat.

Am I easily led astray? Probably. By you. I could have, with profit, spent my money on myself. I always admire the human ability to forgo a pleasure, after that pleasure has been enjoyed.

If I smoked in Trinidad you well knew how I was at pains to hide the fact from you! Why didn't the ass tell me who was the slandering malicious 'friend' who had my welfare so much at heart?

You have insulted me, Kamla. This is going to be my last letter to you. I am easily led astray! Not you, who are fool enough to believe what one ass has said. This could have been entertaining, but you went all out to play the Hollywood role. At other times you kept us without letters for nearly three weeks. Now you dispatch three sermons. Vido is going to the bad. Stop him! He can't help himself, poor thing. Then the one to me: 'You want me to be happy. But how can I?' All this is very fine. Leave me out in future of all your daydreams. Try them on some English or Asiatic ass.

For three weeks past, I have been smoking. As much as with Springer and Co. when you were here. That is bad, isn't it? I have been drinking excessively? Well, yes, water. It has been very hot. Listen, what have you people got against Owad? I can tell you, Miss Hollywood, he is not a whit worse than any of your cousins. Of course, this will confirm, in your mind, the fact that I have gone to the dogs. But I don't give a damn what you think now. You have insulted me in the worst manner possible.

V. S. Naipaul

Miss Kamla Naipaul,

Women's Hostel,

Banaras Hindu University,

Banaras,

India

Trinidad

November 24, 1949

My darling,

I want you to promise me one thing. I want you to promise that you will write a book in diary form about your stay in India. Try to stay at least 6 months -- study conditions; analyse the character. Don't be too bitter. Try to be humorous. Send your manuscript in instalments to me. I will work on them. I am getting introductions to quite a number of people -- Pagett of Oxford included. Pa can put me on to Rodin, the star-writer of England's

Daily Express. Your book will be a great success from the financial point of view. I can see it even now --

My Passage to India: A Record of Six Unhappy Months by Kamla Naipaul.

Don't take everything in such a tragic way. I can't imagine how a girl like you so fond of laughter can't see the hilarious stupidity of the whole thing. If you go ahead taking everything to heart, your whole life will be just one lament.

But let us consider you -- from the practical point. I have already paid back $150, and, by December, $200 shall be struck off. Not bad, eh? If you can't take it -- tell your uncle in London. Find out if his offer still holds good. I trust you are keeping in touch with Ruth. If he says no, well, we'll see then. How much money have you

in the bank?

Has the damned Gov't sent you your allowance?

My stay in Trinidad is drawing to a close -- I only have nine months left. Then I shall go away never to come back, as I trust. I think I am at heart really a loafer. Intellectualism is merely fashionable sloth. That is why I think I am going to be either a big success or an unheard-of failure. But I am prepared for anything. I want to satisfy myself that I have lived as I wanted to live. As yet I feel that the philosophy I will have to expand in my books is only superficial. I am longing to see something of life. You can't beat life for the variety of events and emotions. I am feeling something about everything -- about this amusing and tragic world.

I have found it difficult to live up to my own maxim. 'We must be hard,' I say. 'We must ignore the pain-shrieks of the dying world,' yet I can't. There is so much suffering -- so overpoweringly much. That is a cordial feature in life -- suffering. It is as elemental as night. It also makes more keen the appreciation of happiness.

Please write

to me only how sad you are.

There is one point I want you to help me stress. My thesis is that the world is dying -- Asia today is only a primitive manifestation of a long-dead culture; Europe is battered into a primitivism by material circumstances; America is an abortion. Look at Indian music. It is being influenced by Western music to an amusing extent. Indian painting and sculpture have ceased to exist. That is the picture I want you to look for -- a dead country still running with the momentum of its heyday.

Don't cry, my dear.

Your loving brother,

Vido

Trinidad p.m., September 15, 1950

V. S. Naipaul, Esq.,

62 Westbere Road,

London, NW2

Dear Vido,

It seems you have not yet received my letter. However, you do seem to be all right with cash, and I'm glad.

Your typewriter must be good to type so neatly; but I notice the C & O have a tendency to pile. But this may be due to faulty fast typing.

I hope the Penguin people accept your story. I am curious to see what it is like, but I half guess you would not like me to see it. I'm pretty sure it must be good, though. I can't imagine seeing you write a bad story. When writing a story it is a good thing to read good stories. Good reading and good writing go together. But you must have already discovered this.

Mr Swanzy [BBC World Service Producer, Caribbean Voices, a weekly literary

programme] has paid me some fine encomiums on my short stories in his half-yearly review of

Poems and Prose in Caribbean Voices. The review was also published in the last

Guardian Weekly. On the other hand Mrs Lindo [Jamaican Editor of

Caribbean Voices] has taken me to task for sending in my published shorter story. She tells me that the BBC intended paying me seven guineas for it, but on discovering that the article had been previously published, the price was cut to ú4 and 9/-, from which was deducted 9/- and something in the pound for income tax. So I was left with just $11, if you please. I have heard nothing, so far, about either 'Obeah' or 'The Engagement', though both have been sent up; and I have heard nothing about your poem. You had better write Mrs Lindo to let her know that you are now in England. Maybe she is mistaking you for me.

Have you written Kamla? She seems sad at your not writing her. Do write the girl and say nothing to hurt her feelings. We got a letter from her today, together with yours. She is ill with overwork.

Make contact with people like Thorold Dickinsonç and other big shots in the film and writing business. You never know what good these people may lead you to.

So long as you use your freedom and feeling of independence sensibly it will be all to the good. Do not allow depression to have too much of a hold on you. If this mood visits you at times regard it as a passing phase and never give way to it.

Self-confidence is a very valuable asset and I am glad to know you feel confident; but don't underestimate people and problems.

Write often.Affectionately, Pa

Home, 9/22/50

Dear Son,

Your letter of September 17 we got yesterday. It has made me both happy and -- to some extent sad. I thought that when Simbhoo arrived he would be bringing you and Boysie cheer; that he would make the place a little more like home, with jokes and sightseeing and so on. I should not mind if letters do not come very frequently sometimes. You say Kamla has not written you; and Kamla says

you have not written her.

You write her and try to be kind in your letter. Kamla is only too anxious to hear from you as well as to write you. She probably did not know your address.

I have not failed with my developing outfit. The very first try was a success. I cannot enclose photos with this or else I would have shown you specimens. One photo of my developing I have sent to Kamla. It is Shivan and Baido. A cute little snap. What I need now is a printer -- you know, the equipment on which negatives are printed. Another humbug lies in the fact that I cannot get the right printing paper. Johnsons of Hendon Ltd, London, NW4, have plastic printing frames; more than this, they carry what

they call a new Exactum Printer; also they stock gas-light printing paper of all grades. On this paper printing can be done with daylight. They are very cheap. See if you can send a few packets for me, for negatives, size 120. Also contact printing paper, grades

vigorous, soft and

normal. Tell the people the kind of camera I have, and they should give you the right stuffs for printing.

The Guardian paid me only $5 for the two Ramadhin pictures; and five dollars for the story in the

Sunday Guardian. Before these I think I got $3 for the uncle-aunt picture that came out in the sports page of

TG. But my rice-growing story in the

Weekly carried four pictures. They should bring me in at least $12, but of course you never know with these people.

I have not heard anything further on your poem. You know it has been sent up to London by Mrs Lindo. And I haven't heard more about 'Obeah' and 'The Engagement', which, like your poem, have been sent up; and acknowledged as having been received and retained for possible future broadcasting. Wait and see.

Your writings are all right. I have no doubt whatever that you will be a great writer; but do not spoil yourself: beware of undue dissipation of any kind. I do not mean you must be a puritan. A pity you spent some money badly re meeting Simbhoo; but such things will happen. It was gratifying to hear you could send us some money but everything is all right just now. Are you keeping a savings account? Yes, I think you do; I think you mentioned the fact in a previous letter. S. used to also say some such things to Rudranath when the latter had won his scholarship. I remember S's spirited objection and umbrage. You keep your centre. You

are on the way to being an intellectual. He is only stating a fact. Acknowledge it mentally as such. Say, 'Thanks.'

I never had so much work as I am having nowadays. I hope I shall be able to keep up. I am no longer on the

Evening News. They have shifted me to the

Guardian. Since last Monday -- General Election day -- I have been working, at a stretch almost, from early morning to late night -- nine and ten at nights. Don't see how I can find the time to do features for the

Weekly. Even this letter I write at a snatch. I was asked to write a feature on faith-healing at about 12.30 yesterday; and I had to turn out the stuff first thing in the morning. The faith-healer's meeting that I was to describe actually never finished till midnight. This was last night. But I have turned in the story. What is strange is that I think it will be a good story -- snappily written.

I like your decision to write weekly. I think I can easily manage writing once a fortnight providing the air-letter form is at hand! And providing that the letter, having been written, gets posted!

I haven't bought the tyre. It will get bought when it comes to my not being able to go out -- unless I had one. Like buying the battery. Let us know what is happening. Tell me about the fate of the poems you have sent in, and the stories. And don't worry about anybody or anything here.

No fear; we received all your letters. Only I find they took a long time in the coming. Once three letters, differently dated, came in a batch. Altogether we've got seven letters from you from the day you left home; plus a cable.

No harm in kissing a girl, so long you do not become too prone for that sort of thing.

Love from everybody,

Naipaul

Copyright © 1999 by V. S. Naipaul. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.