Chapter 1

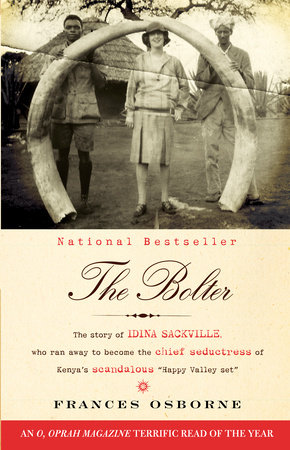

Thirty years after her death, Idina entered my life like a bolt of electricity. Spread across the top half of the front page of the Review section of the

Sunday Times was a photograph of a woman standing encircled by a pair of elephant tusks, the tips almost touching above her head. She was wearing a drop-waisted silk dress, high-heeled shoes, and a felt hat with a large silk flower perching on its wide, undulating brim. Her head was almost imperceptibly tilted, chin forward, and although the top half of her face was shaded it felt as if she was looking straight at me. I wanted to join her on the hot, dry African dust, still stainingly rich red in this black-and-white photograph.

I was not alone. For she was, the newspaper told me, irresistible. Five foot three, slight, girlish, yet always dressed for the Faubourg Saint-Honoré, she dazzled men and women alike. Not conventionally beautiful, on account of a “shotaway chin,” she could nonetheless “whistle a chap off a branch.” After sunset, she usually did.

The

Sunday Times was running the serialization of a book,

White Mischief, about the murder of a British aristocrat, the Earl of Erroll, in Kenya during the Second World War. He was only thirty-nine when he was killed. He had been only twenty-two, with seemingly his whole life ahead of him, when he met this woman. He was a golden boy, the heir to a historic earldom and one of Britain’s most eligible bachelors. She was a twice-divorced thirty-year-old, who, when writing to his parents, called him “the child.” One of them proposed in Venice. They married in 1924, after a two-week engagement.

Idina had then taken him to live in Kenya, where their lives dissolved into a round of house parties, drinking, and nocturnal wandering. She had welcomed her guests as she lay in a green onyx bath, then dressed in front of them. She made couples swap partners according to who blew a feather across a sheet at whom, and other games. At the end of the weekend she stood in front of the house to bid them farewell as they bundled into their cars. Clutching a dog and waving, she called out a husky, “Good-bye, my darlings, come again soon,” as though they had been to no more than a children’s tea party.

Idina’s bed, however, was known as “the battleground.” She was, said James Fox, the author of

White Mischief, the “high priestess” of the miscreant group of settlers infamously known as the Happy Valley crowd. And she married and divorced a total of five times.

IT WAS NOVEMBER 1982. I was thirteen years old and transfixed. Was this the secret to being irresistible to men, to behave as this woman did, while “walking barefoot at every available opportunity” as well

as being “intelligent, well-read, enlivening company”? My younger sister’s infinitely curly hair brushed my ear. She wanted to read the article too. Prudishly, I resisted. Kate persisted, and within a minute we were at the dining room table, the offending article in Kate’s hand. My father looked at my mother, a grin spreading across his face, a twinkle in his eye.

“You have to tell them,” he said.

My mother flushed.

“You really do,” he nudged her on.

Mum swallowed, and then spoke. As the words tumbled out of her mouth, the certainties of my childhood vanished into the adult world of family falsehoods and omissions. Five minutes earlier I had been reading a newspaper, awestruck at a stranger’s exploits. Now I could already feel my great-grandmother’s long, manicured fingernails resting on my forearm as I wondered which of her impulses might surface in me.

“Why did you keep her a secret?” I asked.

“Because”—my mother paused—“I didn’t want you to think her a role model. Her life sounds glamorous but it was not. You can’t just run off and . . .”

“And?”

“And, if she is still talked about, people will think you might. You don’t want to be known as ‘the Bolter’s’ granddaughter.”

MY MOTHER WAS RIGHT to be cautious: Idina and her blackened reputation glistened before me. In an age of wicked women she had pushed the boundaries of behavior to extremes. Rather than simply mirror the exploits of her generation, Idina had magnified them. While her fellow Edwardian debutantes in their crisp white dresses merely contemplated daring acts, Idina went everywhere with a jet- black Pekinese called Satan. In that heady prewar era rebounding with dashing young millionaires—scions of industrial dynasties—Idina had married just about the youngest, handsomest, richest one. “Brownie,” she called him, calling herself “Little One” to him: “Little One extracted a large pearl ring—by everything as only she knows how,” she wrote in his diary.

When women were more sophisticated than we can even imagine now, she was, despite her small stature, famous for her seamless elegance. In the words of

The New York Times, Idina was “well known in London Society, particularly for her ability to wear beautiful clothes.” It was as if looking that immaculate allowed her to behave as disreputably as she did. For, having reached the heights of wealth and glamour at an early age, Idina fell from grace. In the age of the flappers that followed the First World War, she danced, stayed out all night, and slept around more noticeably than her fellows. When the sexual scandals of Happy Valley gripped the world’s press, Idina was at the heart of them. When women were making bids for independence and divorcing to marry again, Idina did so—not just once, but several times over. As one of her many in-laws told me, “It was an age of bolters, but Idina was by far the most celebrated.”

She “lit up a room when she entered it,” wrote one admirer, “D.D.,” in the

Times after her death. “She lived totally in the present,” said a girlfriend in 2004, who asked, even after all these years, to remain anonymous, for “Idina was a darling, but she was naughty.” A portrait of Idina by William Orpen shows a pair of big blue eyes looking up excitedly, a flicker of a pink-red pouting lip stretching into a sideways grin. A tousle of tawny hair frames a face that, much to the irritation of her peers, she didn’t give a damn whether she sunburnt or not. “The fabulous Idina Sackville,” wrote Idina’s lifelong friend the travel writer Rosita Forbes, was “smooth, sunburned, golden—tireless and gay—she was the best travelling companion I have ever had . . .” and bounded with “all the Brassey vitality” of her mother’s family. Deep in the Congo with Rosita, Idina, “who always imposed civilization in the most contradictory of circumstances, produced ice out of a thermos bottle, so that we could have cold drinks with our lunch in the jungle.”

There was more to Idina, however, than being “good to look at and good company.” She was a woman with a deep need to be loved and give love in return. “Apart from the difficulty of keeping up with her husbands,” continued Rosita, Idina “made a habit of marrying whenever she fell in love . . . She was a delight to her friends.”

Idina had a profound sense of friendship. Her female friendships lasted far longer than any of her marriages. She was not a husband stealer. And above all, wrote Rosita, “she was preposterously—and secretly—kind.”

As my age and wisdom grew fractionally, my fascination with Idina blossomed exponentially. She had been a cousin of the writer Vita Sackville-West, but rather than write herself, Idina appears to have been written about. Her life was uncannily reflected in the writer Nancy Mitford’s infamous character “the Bolter,” the narrator’s errant mother in

The Pursuit of Love, Love in a Cold Climate, and

Don’t Tell Alfred. The similarities were strong enough to haunt my mother and her sister, two of Idina’s granddaughters. When they were seventeen and eighteen, fresh off the Welsh farm where they had been brought up, they were dispatched to London to be debutantes in a punishing round of dances, drinks parties, and designer dresses. As the two girls made their first tentative steps into each party, their waists pinched in Bellville Sassoon ball dresses, a whisper would start up and follow them around the room that they were “the Bolter’s granddaughters,” as though they, too, might suddenly remove their clothes.

In the novels, Nancy Mitford’s much-married Bolter fled to Kenya, where she embroiled herself in “hot stuff . . . including horse- whipping and the aeroplane” and a white hunter or two as a husband, although nobody is quite sure which ones she actually married. The fictional Bolter’s daughter lives, as Idina’s real daughter did, in England with her childless aunt, spending the holidays with an eccentric uncle and his children. When the Bolter eventually appears at her brother’s house, she looks immaculate, despite having walked across half a continent. With her is her latest companion, the much younger, non-English-speaking Juan, whom she has picked up in Spain. The Bolter leaves Juan with her brother while she goes to stay at houses to which she cannot take him. “ ‘If I were the Bolter,’ ” Mitford puts into the Bolter’s brother’s mouth, “ ‘I would marry him.’ ‘Knowing the Bolter,’ said Davey, ‘she probably will.’ ”

Like the Bolter, Idina famously dressed to perfection, whatever the circumstances. After several weeks of walking and climbing in the jungle with Rosita, she sat, cross-legged, looking “as if she had just come out of tissue paper.” And her scandals were manifold, including, perhaps unsurprisingly, a case of horsewhipping. She certainly married one pilot (husband number five) and almost married another. There was a white-hunter husband who, somewhat inconveniently, tried to shoot anyone he thought might be her lover. And, at one stage, she found an Emmanuele in Portugal and drove him right across the Sahara and up to her house in Kenya. He stayed for several months, returning the same way to Europe and Idina’s brother’s house. Idina then set off on her tour of the few British houses in which she was still an acceptable guest, leaving the uninvited Emmanuele behind. This boyfriend, however, she did not marry.

Even before that, the writer Michael Arlen had changed her name from Idina Sackville to Iris Storm, who was the tragic heroine of his best- selling portrait of the 1920s,

The Green Hat, played by Garbo in

A Woman of Affairs, the silent movie version of the book. Idina had been painted by Orpen and photographed by Beaton. Molyneux designed some of the first ever slinky, wraparound dresses for her, and her purchases in Paris were reported throughout the American press. When Molyneux had financial difficulties, Idina helped bail him out. In return he would send her some of each season’s collection, delicately ruffled silk dresses and shirts, in which she would lounge around the stone-and-timber shack of the Gilgil Club.

A FARM HALFWAY UP an African mountain is not the usual place to find such an apparently tireless pleasure-seeker as Idina. Clouds was by no means a shack: by African mountain standards it was a palace, made all the more striking by the creature comforts that Idina—who had designed and built the house—managed to procure several thousand feet above sea level. It was nonetheless a raw environment. Lethal leopard and lion, elephant and buffalo, roamed around the grounds of its working farm, where “Idina had built up one of the strongest dairy herds in Africa,” according to a fellow farmer who used to buy stock from her. Idina took farming immensely seriously, surprising the Kenyans who worked for her with her appetite for hard work. Like them, too, she camped out on safari for weeks on end. But then, as Rosita put it, Idina “was an extraordinary mixture of sybarite and pioneer.”

Up at Clouds, Idina filled her dining table with everyone visiting the house. She made no distinction between her friends and the people working for her, “including the chap who came to mend the gramophone etc.” The gin flowed. She was “always most hospitable . . . absolutely charming and put one completely at one’s ease and I was bowled over by her,” wrote an acquaintance.

However, behind this hard work and high living lay a deep sadness.

When the poet Frédéric de Janzé described his friends (and enemies) in Kenya alphabetically, for Idina he wrote: “I is for Idina, fragile and frail.” When Idina is described, sometimes critically, as living “totally in the present,” it should be remembered that her past was not necessarily a happy place. Driving her wild life, and her second, third, fourth, and fifth marriages, was the ghost of a decision Idina made back in 1918, which had led to that fall from grace. On the day the First World War ended, she had written to her young, handsome, extremely rich first husband, Euan Wallace, and asked for a divorce. She then left him to go and live in Africa with a second husband, in comparison with Euan a penniless man. She went in search of something that she hadn’t found with Euan. And when, not long after, that second marriage collapsed, Idina was left to go on searching. In the words of Michael Arlen’s Iris Storm, “There is one taste in us that is unsatisfied. I don’t know what that taste is, but I know it is there. Life’s best gift, hasn’t someone said, is the ability to dream of a better life.”

Idina dreamt of that better life. Whenever she reinvented her life with a new husband, she believed that, this time round, she could make it happen. Yet that better life remained frustratingly just out of reach. Eventually she found the courage to stop and look back. But, by then, it was too late.

When she died, openly professing, “I should never have left Euan,” she had a photograph of him beside her bed. Thirty years after that first divorce she had just asked that one of her grandsons—through another marriage—bear his name. Her daughter, the boy’s mother, who had never met the ex-husband her mother was talking about, obliged.

At the end of her life, Idina had clearly continued to love Euan Wallace deeply. Yet she had left him. Why?

The question would not leave me.

Copyright © 2009 by Frances Osborne. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.