Chapter One This story begins some years after the turn of the millennium, back when gangs were persecuted, back before we all joined one. In those days, birds and pigs were still our friends, and we held some pretty crazy notions: People said the planet was warming. Wearing fur was a no-no. Dogs could do no wrong. Back then, we'd pretty much agreed that guns were good, that just about everybody needed one. Firearms, we were all to discover, were feeble, finicky things, prone to laughable inaccuracy.

During this brief moment in human evolution, a professor of anthropology might, for the half-year he worked, fish in the morning, lecture midday, and stroll excavation sites until early evening, after which was personal/leisure time. I was a professor of anthropology, one of the very, very few. I owned a bass boat, a classic Corvette, and a custom van, all of which I lost during the period of this story, the brief sentence I served inside the cushiest prison in the Western Hemisphere, the minimum-security federal prison camp at Parkton, South Dakota.

Camp Parkton, we called it. Club Fed.

As an anthropologist, I had the job of telling stories about the past. My area of study was the Clovis people, the first humans to cross the Bering Land Bridge from Siberia about twelve thousand years ago. As you know, the Clovis colonized a hemisphere that had never seen humans before, and their first order of business was to invent a new kind of spear point, which they used to eradicate thirty-five species of large mammals. The stories I told about the Clovis were not new ones: A people developed a technology that allowed them to exploit all their resources. They then created a vast empire. And once they had consumed everything in sight, they disbanded-in the case of the Clovis, into small groups that would form the roughly six hundred Native American tribes that exist today.

I had a '72 Corvette and a custom van!

Dear colleagues of tomorrow, fellow anthropologists of the future, how can I express my joy in knowing there is only one profession in the years to come, that each and every one of you has become a committed anthropologist? The trials of my life seem petty compared with their inevitable reward: that the turbulent story of our species should end with all its members' becoming experts on humanity.

The fate of the culture we called "America" is certainly no mystery to you. Of that tale, countless artifacts stand testament, and who could fail to hear such a song of conclusion, endlessly whistling through the frozen teeth of time? Yet you must have questions. Dig as you might, there must be gaps in the record. Who is buried in the Tomb of the Unknown Indian? you might ask. Was the hog truly smarter than the dreaded dog? Were owls really birds, or some other manner of animal? So, my dedicated peers, I will share with you how the betterment of humanity began, and let no one claim I slandered the past. I am the past.

I'm not sure I can tell you the exact year this story be- gins, but I'll never forget the day. It was the season in South Dakota in which the Missouri River nearly freezes over-day by day, shelves of white extend their reach from the riverbanks, calciumlike, until they enter the central channel, where the current rips great sheets free and sends them hurtling downstream.

From my office on the campus of the University of Southeastern South Dakota, I could hear the frozen river wail and moan before a lurching crack tore loose a limb of ice. When the day was clear, I could even see from my window in the anthropology building scattered stains of red on the ice, where eagles had landed with freshly snatched fish and stripped them on the frozen ledges. An eagle was a kind of bird, quite large, and it was famous for the boldness it displayed when stealing another's prey. Most birds were about the size of rats, though some came as big as jackrabbits. The eagle, however, weighed in closer to a dog. Picture a greyhound, then add ferocity and wings.

It was a gray, brooding day when Eggers, one of my star doctoral students, stuck his head in my office. He was vigorously chewing something, and the odds were it wasn't gum.

Eggers wore goatskin breeches and a giant poncho of dark, matted fur, which he'd fashioned himself from animal hides begged off the Hormel meatpacking plant at the edge of town. I could smell him long before he made his way to the stacks of cardboard boxes that filled my doorway and spilled into the hall.

"Careful of Junior," I said and waved him in. I had just received an exciting new crate of raw ice-core data from Greenland, and Eggers' booties were covered with God-knows-what.

"Life's good, Dr. Hannah," Eggers said, making his way around the boxes. He displayed that impish grin of his. "Life is good," he repeated.

My office in those days was filled with houseplants of every variety, though I found indoor gardening so pointless and sad I could barely stand to look at them. Eggers ducked under the hanging tendrils of plants whose names escaped me, his feet crunching across the layer of flint chips that littered the floor from the hours I whiled away knapping out primitive tools and weapons.

He took a seat, and I was confronted with my daily update on Eggers' dissertation project, which was to exist using nothing but Paleolithic technology for an entire year. More than eleven months into the experiment, some of the results were already clear: the wafting custard of his breath, the thin mistletoe of his beard, the way the oiled gloss of his face had attained the yellowy hue of earwax.

I should have been working on a grant proposal or grading some of the endlessly simple student papers that flowed across my desk. But I couldn't concentrate, because of Glacier Days, a yearly carnival intended to lighten the gloom of winter by celebrating the recession of the glaciers that had carved the Missouri River Valley. They'd set up the midway in the Parkton Square parking lot, catty-corner to campus, and every so often you'd hear the muffled, rising moan and long wail of young people on the thrill rides.

"Okay, Eggers," I said. "Life's grand. We'll go with that hypothesis."

Eggers shrugged, as if everything was self-evident. "Oh, it's not some theory, Dr. Hannah. Life is tiptop," he said, moving aside a dusty stack of my book, The Depletionists, and settling into a high-backed chair. He slumped enough that his hair left a sheeny streak down the leather upholstery. God, his game bag reeked!

I was about to hear one of Eggers' continuing intrigues with a coed, or how he'd won some prestigious new grant. The anthropology journals were already fighting to publish his story. But I couldn't get that "life is good" phrase out of my head. It's what my stepmother, Janis, kept saying at the end, and it became one of my father's refrains after we lost her. I could see behind Eggers, framed in the window, a piece of ice slowly turning down the Missouri River-it drifted in from the future, caught the sun for a moment, and disappeared out into the past. From the Glacier Days carnival, a slow whoop arose from the next generation of South Dakotans as they mocked their deaths on bloodcurdling rides, and my eyes naturally fell to Junior-nineteen thousand notecards and twenty-seven cardboard boxes of research, all yet to be examined, all those stories waiting to be told.

Eggers shifted what he was chewing and went after it with his molars.

"Is this about Trudy?" I asked.

"Trudy? Why bring her up?" he asked. "Are you feeling guilty, Dr. Hannah?"

"What would I have to feel guilty about?"

"Nothing," Eggers said. "Nothing. Except you did file the paperwork to revoke her Peabody Fellowship and give it to me."

"The school's doing that. That's out of my hands. Congrats, by the way."

"You know me, Dr. Hannah. I yawn at money. Money's obsolete to me."

Eggers pulled something out of his mouth, inspected it, and put it back in.

"Don't gloat," I told him. "Everything will be hunky-dory once I explain things to her."

"Trudy's pretty upset. I mean, I was the one who broke it to her."

"This isn't even official yet."

"She needed to hear it from someone who cared," Eggers said.

"Please," I said. "Anyway, that's only half the story. Losing her Peabody is only the bad news of a good-news/bad-news thing. I'll explain it to her."

Eggers swallowed hard enough to make his eyes water, and then he opened the flap of his game bag. I could see a fuzzy tail sticking out of it, and it hadn't escaped the notice of the school paper that all the squirrels on campus had disappeared during the time that Eggers, an adult omnivore, had taken up residence in the middle of the quad.

"I wouldn't worry about Trudy," Eggers said. "Trudy can take care of herself. She'll bounce back." He removed another sinewy morsel and slid it into his mouth. Though grayish-brown, it crunched like celery. He chewed it contemplatively. "I've got my own good and bad news," he added.

I removed my glasses, folded them, rubbed the bridge of my nose.

"Just the good," I said. "Only tell me the good."

"I found something."

Eggers was always finding things. He was the only person in town who walked everywhere, and over eleven months, his travels on foot had netted him countless arrow points, bison skulls, mastodon teeth, and a brass bell that may or may not have belonged to Meriwether Lewis. Sleeping in the same stretch of sand in South Dakota, you were likely to find a buffalo soldier's pistol, a conquistador's breastplate, the hooves of rhino-pigs from the early Eocene, T-rex teeth, and maybe even a Cambrian trilobite, frozen mid-wriggle at the dawn of time.

"Is it a spear point?" I asked.

"It's a point, all right," Eggers said.

"A Clovis point?"

Eggers shrugged, but in a way that said, You can bet the farm.

I threw a foot up on my desk to lace my snow-packs. "Show me," I said.

We tromped downstairs and cut through the Hall of Man, a natural-history exhibit that my predecessor, Old Man Peabody, fashioned himself back in the 1960s out of an empty classroom. The Hall was about thirty feet long and lined with glassed-in exhibits. On one side was a series of models depicting glacial advance and retreat during the late Pleistocene. Peabody had crafted the balsa glaciers by hand, painted them white, and used little stickpins to represent Clovis movement from Siberia to South Dakota during brief openings in the ice. On the other side of the Hall was an amazing series of very lifelike models that followed the ascent of humanity: in a row were displayed Homo habilis, erectus, and sapiens, followed by Neanderthal, and finally Clovis, all posed in natural settings with several artifacts that Peabody had excavated himself. This hall is where I came to pace and think in times of doubt. Simply to cross the room was to travel a hundred thousand years back in time; it was a place where things always seemed clearer to me.

Out in the quad, Eggers and I walked quietly through the snow. The limbs of the maples had been shorn off, so they were whitened posts against what was for now a clear sky. The sidewalks were sanded and salted, though we veered off through the hackberry trees, walking under their weblike branches and listening to the tap-tap of thawing icicles as they dripped constellations into the snow below.

Eggers' shelter was situated in the middle of Central Green, and ahead I could see its snow-crusted dome, made from six curving mammoth tusks draped with a mass of various animal hides that had been confiscated over the years by the Fish and Game Department. Also ahead in the courtyard was a large granite stone that held the plaque I'd placed in remembrance of my stepmother, Janis, and I was faced with my almost daily decision: should I offer a word to her, or should I close my eyes and simply walk on?

The proof of my cowardice was that my decision to talk to Janis always came down to whether or not I was alone. At least I didn't put a bench here, which I'd considered.

Eggers could see the apprehension on my face. "Maybe I'll just go check my snares," he said, and headed toward the arbor-vitae hedge.

"No, don't," I told him. "I'm okay." And like that, I resolved not to speak to Janis today. As I neared, though, I did look at her face, fixed in the mild relief of bronze. The birds had been crapping again, something I hadn't planned on when I'd commissioned the memorial. But, really, did it matter? How could someone be honored by impressing a face on a plaque or a name to an anthropology fellowship? I couldn't even decide if I should use an image of her from when she was young or when she was older. Eventually, I chose a picture taken on the day she graduated from stenography school, a time before she even met my father. She looks young and expectant in the image, but the ironies didn't escape me: since she left my life, I'd chosen to remember her with an image from before I'd entered hers. So now we looked upon each other as strangers.

My father had Janis cremated, something I'm against, but would it have made a difference if we'd buried her? Ten thousand years from now, when people exhumed her bones, what would they know of her life, her spirit? There would be her rings, traces of gold dentistry, perhaps. Would they know of her love of plants, that she longed to see Egypt, or that when she napped on the couch her fingers would type her dreams on her lap? Would the future know her goal in life was an impossible one: to be my mother after my real mother made a stranger of herself? Should I have put medicine bottles and a bedpan in her grave, so the future would understand her final struggle? Should I have chiseled out her story, start to finish, in granite, and what language will the future speak?

The snow thinned as we crossed Central Green, and it wasn't until you neared Eggers' dwelling, which he called his "lodge," that you realized it was situated, as if by chance, atop the one spot on the whole campus where there was no snow. There were underground steam tunnels that sent heat to the dormitories, and Eggers claimed it was just a coincidence that he had built his lodge over the main heat exchangers. Nearing, we stepped through shards from his flint knapping, and an array of his stone tools was lying around-scrapers, cutters, and percussion strikers. Finally, there was a rather shocking mound of bones that Eggers had accumulated over the year. I nosed through them with my boot-most of the bones were surprisingly small, shining dully from under a gelatinous goo that beaded water away, and though rodent anatomy was technically out of my field, I spotted among the prairie-dog and squirrel skulls more than one feline. Eggers was saving them so he'd be able to calculate his caloric intake, once his year was finished and he could handle lab equipment again. These bones were the cornerstone of his dissertation, and I counted them as a real document, as good a testament to Paleolithic culture as any. To keep scavengers away, Eggers urinated on the heap.

When Eggers pulled back the flap of his lodge, he was greeted by a package, wrapped in red paper and tied with yarn, and there was only the faintest smell of fire smoke. Of the gift, probably left by one of his female students, Eggers seemed to take no notice; instead, after the flap closed behind him, I heard him breathing on the fire, a patient, well-paced stoking that made me look away, as if this was a private moment between man and flame. Low clouds had again passed over the river, and of the Clark Bridge, only the upper trestle was visible.

Eggers emerged with a soft leather cloth that looked exactly like a chamois you'd use when washing a car. "This Clovis point is the cover of the Rolling Stone," Eggers said, handing it to me. "This is a feature article in Archeology Today."

Through the leather cloth, I felt the weight and shape of the stone. You never forget the feel of a Clovis point. A hint of pink was peeking from under the cloth.

"You know, I've never found an exotic one," I told Eggers. "In all my years of hunting. I've found some things, don't get me wrong, but never a colored Clovis point."

"Well, this one's yours," Eggers said.

I unfolded the cloth, and there it was. About five inches long, broad-headed, and cut from the rarest of materials, a semitranslucent rose quartz. Twelve thousand years ago, this artifact was the height of technology on the face of the earth, and no one in the millennia since has been able to reproduce the Clovis' lost craft. The afternoons I spent flaking flint in my office were merely exercises in humility, for the Clovis concerned themselves with nothing but producing the most dangerous weapons on earth. They left behind no art, no monuments, no shelters, few remains.

I ran my fingers down the dimpled spine of Eggers' pink point-the cutting edge was covered with serrated ridges that fanned forward to cause severe micro-hemorrhaging on penetration, while at the same time the plane of the blade was fluted with a ridge leading backward, serving as a channel to runnel the blood from the wound. This blade could snap bison ribs and still slice tomatoes.

Over the course of three centuries-at the end of the Pleistocene epoch, twelve thousand years ago-three amazing things happened: the Ice Age ended completely, and glaciers retreated from North America; humans entered the hemisphere, and these Paleo-Indians we call Clovis quickly spread across all forty-eight contiguous states, founding an empire that included Mexico and Canada before their culture came to an end; and, finally, thirty-five species of large North American mammals became extinct. All in three hundred years.

Mammoth and mastodon skeletons have been found with dozens of Clovis points lodged in their bones. Many paleo- anthropologists agree that the Clovis people eradicated the elephants of North America, though they tend to believe the other large animals were killed off by climate change.

It was my lone hypothesis, however, articulated in The Depletionists, that the Clovis blade was the demise of the North American camel, the giant sloth, the short-faced bear, and thirty-two other large mammals. And here was the very spear point that had done it. I marveled at its color, held it to the light, and saw that the quartz was clear at the surface with a cataract of milky pink veined through the center. Only a few thousand Clovis points had ever been discovered, and they were all logged in the National Clovis Bank. Fewer still of these super-bleeder spear points were cut from the exotic minerals only Clovis had a fondness for: smoky purple obsidian and ferrous chert, from feldspar, perlite, spider flint, or the blue-yellow of anthracite. And here was rose quartz. In the back alleys of anthropology, there was a black market for these points, and what I held was worth more than my Corvette and custom van put together.

"Okay," I asked Eggers, "where'd you really get this?"

"I told you," he said. "I found it."

An anger rose in me. "You found this and then removed it from the site? This point doesn't mean anything without context. Haven't I taught you anything? Unless it's in situ, where we can see its role in the bigger story, it's just a bauble."

"It's more complicated than that," Eggers said. Students were filing out of Gufstason Hall, and his eyes followed their brightly colored jackets as they descended the slushy stairwell, arms out for balance, in baby steps. I looked at my wristwatch. It was just after noon, and my father would be waiting for me.

"I've got to teach my Arc-Intro," Eggers added. "There's more than this spear point. I'll show you, but I need to ask a favor first."

Doing a favor for Eggers was no easy thing. He didn't use money, ride in cars, or borrow music. He didn't need my fishing pole or want a letter of recommendation. He'd been an unexceptional kid as far as I could tell, one who sat at the back of my classes, dressed like a golf caddy, and probably smoked some reefer. Then he embarked on this project, and somehow he'd become a lean, clear-eyed young man who had no need for anything from you but time, muscle, and wisdom.

"All right, what is it?"

"Meet me here tonight, when the moon is high."

"Surely, you're joking," I told him. "What time is that? Midnight?"

"Midnight sounds right, though I'd have to check the moon."

"Midnight's my personal/leisure time."

"And bring Trudy," he said. His big, shaggy figure was already heading off to teach.

I stood there a moment with the pink Clovis point in my hand. It felt wrong simply to stick it in my coat pocket as if it was a pen or a throat lozenge, and it seemed more criminal to wander the campus wielding it in my hand. I probably shouldn't admit this, but my first, brief impulse was to show Janis, to walk up the hill to the plaque that I tried to think of as her, and tell her all about it.

I admit this because these events happened long ago, and it's more than ironic that a man who spent his career trying to bring the past to life would, around the age of thirty-nine, begin to communicate certain things to the dead.

That's when Eggers came walking back to me. I was still standing there, hand extended with a pink spear point, looking toward the river so as not to look toward my stepmother. As Eggers neared, I for some reason felt that when he came close he would keep coming closer and give me a pat on the back or clasp my hand. He might hug me, I thought.

Instead, Eggers said, "Are you okay, Dr. Hannah?"

"What?" I asked.

"I better hold this for now," he said, taking the point from my hand. "I'll give it back later tonight. And get some rest, yeah?"

Then he walked away again.

I set off through the quad, following the snowed-in cardio-track, with its frozen fitness stations, then tromped past the Carney Aquatic Center, standing like a cube of jade with its steamed-up walls of Depression-era glass. I could make out the silhouettes of dive platforms, could almost smell the endless drizzle of mildewy rain that dripped from the glass ceiling inside.

There was no getting around the fact that I would be late for lunch with my father downtown, but still I cut through the dean's courtyard and the president's garden-the ground winterized with rows of burlap-and it struck me as I passed among the stark colonnades surrounding Old Main that the school paper was right: all the squirrels had disappeared.

The campus opened onto Parkton Square, a one-block park surrounded by multi-story brick buildings erected by people who believed towns like Parkton and Sioux Falls would one day be Kansas Cities and St. Louises. Parking was free dur- ing Glacier Days, so I walked past green-hooded meters in front of businesses that were mostly alive, though the Bijou Theater was now an indoor shooting range and the Independent Order of Odd Fellows lodge had been divided into the small apartments where my father now lived. If I looked up to the hill above downtown, I could see the library and buildings of Parkton College, the long-bankrupt Catholic school that was now home to the minimum-security federal prison camp.

I crossed the street at Bank, passed the statue of Har- old McGeachie, "The Farmers' Farmer," and watched a roller-coaster car swoop above the trees in the park. It climbed its white scaffolding, paused atop the hump to let its passengers fret and moan before the load of colored hats, thick parkas, and trailing scarves plunged screaming from view. Before I pushed into the brass revolving door of the Red Dakotan, I paused to read the movie marquee next door, which was billing a double feature of "His & Hers Pistol Special" and "Super Scope Sale."

The Red Dakotan had been built long before the dam, back in a time when Mississippi steamboats made it this far up the river, when wealthy passengers needed a place to freshen themselves and pass the time in luxury while military prisoners restocked the ships with coal. Inside, the wool carpets had a red fleur-de-lis design, and there was a staircase banister scrolled in the French style. Silver "smoker's companions" stood astride each chair. By the bar, below the Dakotan's wall-length gilt mirror, I spotted my father's houndstooth sportcoat.

When I joined him, he was holding the hand of a woman who was leaving. He bowed slightly to her, extended a business card between two fingers, and said, "Enchanté," before hailing the bartender with an order of two martinis.

He wore a new pair of eyeglasses with amber lenses, tinted like the safety goggles that shootists wear. He sported a mustard-colored vest, and he'd acquired a pinkie ring that was nothing but a huge nugget of gold. Here was my father, a man who in the six months since Janis' death had managed to liquidate everything they owned together, sell his State Farm office, and reappraise all of southern South Dakota with a look in his eye that said, I'm ready. Man, I am ready.

"Enchanté," I said.

He pretended not to hear me.

"Did you bring the Corvette?" he asked. "I may need the 'Vette later."

"Let me see one of those cards," I said, reaching for his breast pocket. "I mean, I take it you didn't just try to sell that young woman insurance."

He brushed away my hand. "You wish," he said. "It happens I will be escorting that new lady friend to the radio theater tomorrow."

I swiped one of the cards anyway. It read, "Frank Hannah," and below, in fine script, "Appraiser of Fine Goods, Objects D'Art, & Rare Beauty."

I said, "I notice you didn't mention the word 'Antiquities.'"

Dad gave me his "wise-sage" look, which consisted of lowering his head enough to eyeball me over the top rim of his glasses. "Son," he said, "every woman has something hidden and valuable she wants to show you."

"Like her underwear?"

He snatched the card back. "This wouldn't work for you," he said. "Look at your limp suit and mail-order spectacles. Who taught you how to shave? I woke up. I stepped out of the fire."

He thumbed the length of his lapels and tugged his cufflinks, as if to say, See?

"The fire? You mean the inferno that is marriage, fatherhood, and a career?"

"Hey," he said, "I'm still your father. Don't forget that. But here's a tidbit I woke up to. There's no such thing as insurance. You don't bet against doom. You can't sell policies your whole life and just hope disaster doesn't come. You got to tip your hat when it comes, because it's coming. So-send in the tornadoes. Let's have the locusts."

"I hope you've been drinking," I said.

At the sound of the martini shaker, Dad closed his eyes. To the music of ice and frothy gin, he said, "Oh, lighten up. These are just musings. This is only Philosophy 101. If I wanted to give you real advice, I'd tell you to find a young girl, ten years younger, and marry her young. That's as close as you'll come to insurance."

Of course he was referring to the death of Janis, but we had, at some point since then, come to a silent understanding: he never spoke my stepmother's name, and I never said my mother's.

Dad's eyes popped open. "Come to think of it," he whispered, "forget the Corvette. I may need the van tonight."

He smiled for the first time, and I saw that his two front teeth, which had always been a tad discolored and out of alignment, now gleamed perfectly white with new crowns.

The martinis came, both dressed to my father's exact specifications-a toothpick skewering an olive, then a folded anchovy, and finally a cocktail onion-so I knew my father had walked the bartender through a couple trial runs before I'd arrived.

Dad put some cash in the bartender's hand. "We'll want that booth over there, by the wall, and we'll need our steaks sent over ahead of time." He turned to me. "Two or three steaks?"

I looked around for Trudy, who was supposed to meet us for lunch, but she was nowhere to be seen. "Two for now," I told Dad.

"Two it is," he told the bartender. "Make them porterhouses, keep 'em rare."

Then my father lifted his glass high, a thin film of fish oil catching the light.

"To floods and hail and the Great Deductible," he said, and drank alone.

In the Parkton landfill was Janis' Art Deco cocktail set, complete with flamingo-pink martini glasses and a tortoiseshell shaker. Gone also were her Bakelite clutch purses, her collection of dime-store brooches, and a little library of vintage etiquette guides, which her mother had taught from in the days of elocution. Dad had lightened his heart by shedding-the house, the furniture, the car-and, as if Janis' spirit was small enough to inhabit anything, nothing they'd shared was spared, not the nail clippers, the alarm clock, the plastic ice-cube trays. He even ditched his own glasses, because they had once brought her into focus. Now my father lived in a tiny apartment, and except for a fair amount of money he needed to give away, there was no evidence that my stepmother had ever existed.

I had two theories on my father.

The first held that he had fallen out of love with Janis at some point in their marriage, and that her death, while not pleasant for him to watch, was an overdue relief. This father before me now, yellow-tinted glasses, raw gold ring, was the man I'd always have known, had he not been hobbled by some marriage vows, a nine-to-five job, and a conscience as old and guilty as two men's.

I sipped my martini-it tasted appropriately oceany, and though I wasn't much of a drinker anymore, it struck a long, clear note in my head. The second hypothesis had to do with my mother, but it would get no sympathy in this room.

My father looked at his watch. "Okay, so where's this Trudy?"

"She should have been here by now. I told her to meet us a half-hour ago."

"She's not like this caveman guy of yours, wearing pelts and crapping in the bushes? Jesus, let's give the money to that poor fool."

A long-ago ocean, that was the quality of my drink, but shot through with sonar pings of alcohol. On my tongue, the ancient brine of salted fish and olive mixed with the bright light of oniony gin.

"That caveman," I told my father, "has a grant from the Carnegie Foundation. He won an outstanding-dissertation- proposal award from the Academy of Arts and Sciences. Then he goes and wins funding from the state Heritage Council and the Bureau of Land Management. Now my department chair has decided to give him our only graduate fellowship, the Peabody, so Eggers will have to acknowledge us in his book. And this kid doesn't even spend money."

"Does he wear drawers under those skins?"

"I don't believe so, Dad."

He cringed. "I suppose toilet paper's out of the question."

"Eggers used leaves for a while, and I'm sure there'll be a chapter in his dissertation about the poison-oak incident. Now I believe he's winging it."

A waiter in a red jacket beckoned us, and I could see that atop a freshly linened table sat a pair of steaming porterhouses. The steaks had come so fast, they must have been cooked for other people, who would now have to wait longer.

"How much did you tip these guys?"

My father shrugged and began to make his way through the tables, drink high. As I followed, it became clear to me that most of the customers were farmers and ranchers from smaller towns, like Doltin and Willis, people who made the trip in for Glacier Days and were now having a late lunch at the one nice place in town.

My steak was closer to medium, but cooked to perfection, from marbled beef that was probably slaughtered that morning at Hormel. The veins of fat had melted away, and I alternated the meat's flaky butteriness with shocks of warming gin. For a while, the two of us simply ate, and every few bites I had to lean back against the red, rolled leather of the booth to remind myself I was alive. In those moments, with my head near the wall, I could make out the faint pop-pop of people firing their pistols in the converted movie house next door. The sounds were no more disconcerting than the faint screaming you'd once hear if you ate during the horror matinee, so my digestion was unaffected. I'd never heard a gun fired in anger, let alone fear, and I had no way of knowing then that before that winter was out, an evening would come when all the people in our great nation would fire their weapons at once.

Finally, I set my fork aside. I hadn't even touched the carrots, let alone the hot rolls, but my father lifted his bone with two hands. "So what do students have to do for this fellowship money?" he asked, and raked his bottom teeth along the underside of the bone.

"Nothing, really. It supports them while they study or research. They just keep doing what they're doing. But this money is going to make a big difference to Trudy. She's studying Paleolithic art. The Clovis is the only known culture in the world that left no art behind. There are just a lot of points and blades. Trudy believes that weapons were their art. It's a whopper of an idea. She's maybe going too far with her feminist angle, but the premise is sound."

"Are you sleeping with her?"

I tossed my napkin on the table.

"Really, Dad. You didn't just say that. This fellowship you're endowing is going to make all the difference for her. She has to travel to the cave dwellings in New Mexico, see the petroglyphs in Arizona. She needs to do comparative blade analysis all over North America, France, and of course Peru."

"Hell, I could use a trip to France."

"Bon voyage," I told him.

Two waiters walked by, carrying a single tray between them. On it was a cut of meat called "The Cattleman." There was no shortage of pomp in its delivery, yet the steak was the real deal-beyond large, it was the size of a saddle. If you could eat it, it was free, and the steak's new owner seemed embarrassed only by the fact that this indulgence was a public event.

"What's she like?" my father asked.

"Trudy? She's pretty dang smart, for starters."

"What's she look like?"

"Physically?"

"Yes, physically."

I had no desire to explain Trudy to my father. Her application for the Peabody Fellowship had given me her racial breakdown: a mix of African, French, Korean, and Japanese. With her height, her close-cropped hair, and those shoulders, I occasionally imagined her as a prototypical Clovis woman. It was an inappropriate fantasy, I knew. Scientifically, it was flawed as well-real Clovis were certainly smaller, more compact, and probably poorly nourished. Yet I couldn't help, at times, imagining her body in motion as she hunted down a giant Pleistocene glyptodont.

"She's big, Dad. Five foot nine, probably a hundred eighty pounds."

He worked the last bit off the bone, so all that was left was the white vertebral shank and the descending postilum.

"Big num-nums?"

I shook my head no.

"So this girl," Dad says, "if she's so needy, how come she can't even show up for a free steak?"

"I think she's a little mad at me right now."

"You are sleeping with her."

"No, no, she has a fellowship, the Peabody, but the school's taking it away and giving it to the caveman. It's just miscommunication. She doesn't know about your fellowship yet, the Hannah."

My father pointed the steak shank at his own chest.

"Well, what do I get out of this fellowship-donor thing?"

"Immortality, Dad. Your name gets to live forever."

I expected him to laugh or smart-ass, but he said nothing, just set aside the bone and reclined, hands on chest, against the plush leather. He ran his tongue along his teeth, then asked, "You ever met anyone who really wanted to live forever, one person who just wanted to keep going and going?"

I shrugged. "I suppose not."

Dad leaned forward. "Then no fucking plaques of me when I'm dead, okay?"

When the moon looked high in the sky, I set out from my little apartment by the river, and made my way to Trudy's. She lived alone in a small graduate dorm by the cafeteria, and you could still catch a scent of fried egg rolls in the air from the meal plan earlier that night. It began to snow as I walked, so softly at first that I couldn't tell for sure when the flakes started coming down, but by the time I stood in her courtyard, there were yellow curtains of snow hanging under the campus floodlights.

When I knocked, the flimsy dorm walls shook, rattling the neighbors' windows, and the sound off the hollow-core door was loud enough that three other students stuck their heads out to see if it was for them. But Trudy didn't answer.

"Trudy?" I called.

"Go away, Dr. Hannah."

"Please listen to me, Trudy. I know you're upset that the university took your fellowship away, but we have a better fellowship for you."

Inside, I could hear her pour a glass of water.

I spoke into the peephole: "If you could just listen to what I have to say."

"There's a fellowship in Arizona I could apply for," I heard her say. "And that postdoc at Stanford, unless Eggers already has it spoken for. I was dragged all over the world my entire childhood. No need to put down roots here, I guess."

My voice raised in pitch as I tried to reassure her. I even took out my inhaler, just in case I needed it. "Everything's going to be okay, Trudy. This is a better fellowship. You'll like it much better."

"Don't tell me 'everything's going to be okay,'" Trudy said. "Don't tell me what I'll like and not like. I want my Peabody back. That's the fellowship I earned."

"You'll be the first recipient of this new fellowship. My father has established the Hannah Fellowship, in my stepmother's name, and after careful consideration, you've been chosen as the first recipient."

Trudy opened the door, her hand holding a tumbler of water, half full. She wore her usual paint-speckled jeans, a sweater of chocolate wool a shade darker than her skin, and she'd had her hair cut even shorter since I'd seen her last. My God, those cheekbones. I stole a quick puff off my inhaler.

"I'm the one who should be knocking on your door late at night, telling you how I feel," she said. From behind her came a tide of warm air, smelling faintly of turpentine.

"Okay," I said. "How do you feel?"

Trudy shifted in the doorway. She took a drink of water. I could see she'd been repainting the walls of her dorm room with ancient cave drawings and symbols.

"Well, I'm pissed off," she said, sounding reluctantly justified. "I've got good ideas. My Clovis theory isn't even out there in the literature. Nobody's articulated it. And all I hear about is Eggers. What's his idea? He doesn't even have one. He has a gimmick."

"Trudy, I recruited you, remember? I've always believed in you. I don't know how you'll ever prove it, but your dissertation hypothesis is brilliant. For a culture based on making animals extinct, to fuse weaponry and art only makes sense. The part about women carving all the spear points while the men hunted-well, you'll maybe have to gather more data on that."

"I've smelled Doritos on him," she said and paused to let that sink in. "Dorito breath is unmistakable. Did you know he doesn't read the textbooks he assigns? He doesn't even use chalk, because it's 'technology.' He gives his tests orally, and gets one of those girls of his to bubble in the grades on his grade sheets. Do you know how many bubbles I bubble in? And he's Mr. Primitive? Look at how I live. I steal toilet paper from the faculty bathroom. I'm eating noodles and oil in here. If my car breaks down, I'm the one who has to fix it."

"Doritos, huh?"

"Spicy Taco flavor."

"Look, Trudy, I'm going to need a favor from you."

"I'm not done yet," she said.

I put my hands up, as if to say, No offense, I come in peace.

"That was my fellowship," she said, pointing at me. "Mine."

Trudy looked as if she was gearing up for a speech, but then, as if she'd heard her own words from afar and decided she didn't like their tenor, she stopped. "Okay, I'm done now," she said.

I waited a moment, to be sure she was through, then said, "This favor I need, it involves meeting Eggers, but the favor's for me."

Now she waited a moment, looking at me with her head cocked.

"Is that for real?" she asked. "That this fellowship's named after your mother?"

The fellowship was in honor of Janis, but I didn't correct her. I didn't answer at all. Trudy seemed to see in my eyes that this was a subject about which I would not lie. She shook her head, as if disgusted with herself, then disappeared into her dorm room and returned with a heavy scarf.

"Okay," she said. "Let's go."

We crossed the courtyard together, passing a solitary picnic table frosted with white. Trudy steered me around the blanket of snow that hid the sunken volleyball pit. Black slush lined the edge of the Honor Roll Parking Lot, and as we trudged through it, heading for the quad and Eggers' lodge, I couldn't help noting the natural grace and authority with which Trudy moved.

It would be less than ethical of me if at this point I did not confess that I believed Trudy was the ultimate female specimen. Intelligence and beauty aside, and from a strictly professional anthropological perspective, her body was perfectly evolved-tall frame, thick bones, and long muscles-a decathlete's physique. Her back flared into broad, square shoulders that framed a strong chest marked with small and unobtrusive breasts, and she carried just enough fat to optimize insulation and energy reserves without compromising mobility. I'd seen her body articulated once as she swam butterfly inside the jade cube of the Carney Aquatic Center, the points of her rotator cuffs launching each stroke, causing a wave that ran through pectorals, abdominals, and quadriceps before she cracked into a dolphin kick with the cablelike snap of her Achilles tendons. This was not the body of a gatherer. This was a person who could walk into any society, historic or prehistoric, and demonstrate abilities that were absolutely commanding. Of course I kept such thoughts to myself, lest I appear lecherous, or just plain old-fashioned.

We followed a thin column of woodsmoke toward Eggers' lodge, which lay in the darkness ahead. Janis was a shadow in the trees uphill from us, and the whole campus was quiet except for one soul. Out in the quad, a lone student was running the fitness track in the late cold. He jogged in his parka until he reached the pull-up station, where his breath plumed upward each time his chin crested the bar. After a certain number, he ran on.

Eventually, we reached the muddy, snowless circle that surrounded the lodge, and were met with the charring smell of an odd, sour meat. With a lift of the flap, Eggers emerged in a bizarre set of pantaloons and a huge serape of black fur. He saw we were looking at the strange hat of rabbit hides on his head. "It's not finished," he said. "Come on. I spend half my life gathering wood, and the other half melting snow."

"Here we are, Eggers," I said. "What's this favor?"

"It involves our new Clovis point," he said.

Trudy narrowed her eyes at him.

"There are no new Clovis points," she said. "Unless you think you're the one person in the world who can make them."

"I have a real one," Eggers said, "and we're going to use it." He ducked into his lodge and returned with a heavy spear, about two and a half meters long, the pink Clovis point bound to the end with some kind of thin fiber.

"Are you crazy, Eggers?" I asked. "This is an artifact. It's invaluable."

"No, sir," he said. "This is a tool, made to be used, and the only thing I still need to do for my dissertation is bring down a large herbivore. This is your idea, Dr. Hannah. This is straight out of The Depletionists. I don't care what your critics think. I read that book ten times. Your book is why I'm doing this." He gestured at his lodge, his clothes. "Don't you want to see if it's true, if this point can really do it?"

"There's no need," I told him. "These points have been found lodged in mammoth and mastodon bones. There is no doubt they kill."

"You can shoot an African elephant ten times with a rifle and it will only get angry," Eggers said, gesturing a little wildly with the spear. Trudy and I backed up a step. "Fifty years later, when that elephant dies of old age, it leaves bones with bullets in them. Maybe your mastodons were the ones that got away. You ever think of that? But how can you know, without research and testing?"

Trudy laughed. "And where are you going to find a mastodon?"

Eggers turned to me. "All I need is an animal that weighs at least a thousand pounds. Isn't that right, Dr. Hannah?"

"Well," I said, "I suppose."

My head was starting to spin a little. I kept seeing pink spears flying into the future-where would they land? Most of my colleagues believed climate change at the end of the Ice Age had killed off all the big animals in North America, which caused the Clovis to starve and disband; but I'd staked my whole career on the belief that a Clovis point could take down any animal. Yet Eggers was right-I'd never seen a kill.

"Where are you going to find a thousand-pound animal that no one's using?" Trudy asked. "Those guards at Hormel mean business. They'd grind you up and turn you into an Eggers burger."

"Don't you worry about Eggers burgers," Eggers said. "Eggers has this all planned out."

I put a hand on Eggers' shoulder. "Is this the bad news?" I asked. "You know, the bad part of the good-news/bad-news thing?"

"The bad news comes tomorrow," he said. "This is the celebration part." With that, Eggers began backing into the darkness of the quad.

Trudy and I stood there a moment, looking at each other.

"Did you see that Clovis point?" she asked. "A woman made that. I know it. It took her hours, sitting around a mineral deposit with her friends. She talked and told stories while her hands worked the quartz. She chose the material for its beauty, because this was her art, and the design was taught to her by her mother-the keeper of a thousand years of hunting technology."

While Trudy spoke, I pictured her hands working the quartz, holding the point up to the light to search for imperfections, then testing its edge with her thumb.

We both reached the same silent conclusion, then set out after Eggers, following his tracks in the snow, though the vaporous trail of his body odor left no doubt as to his course. By the time we reached the dean's garden, we were abreast of him.

Trudy stuck her hand out.

"Let's see this so-called spear," she said.

She inspected the spear by pointing it toward the moon and turning the shaft to see if it was straight. Then she examined the blade. "It smells like mint," she said.

"It does not," Eggers said.

"Is this dental floss?" she asked. "You tied this point onto the shaft with dental floss, didn't you?"

I was only half listening. In my head, I was animating Clovis points. They flew and flew, waves of them. What had seemed like abstractions were coming clear. I saw a spear fly from dark hands into a gleam of bright light before passing into the haze of its victim.

Trudy said, "Dental floss, unless I'm mistaken, is made from wax-infused monofilament, which is derived from modern polymers. Did the Clovis use petrochemicals, Dr. Hannah?"

"Listen," Eggers said. "Do you know how long it takes to dry and string catgut? I've done it. I know."

By now, we were in the Old Main's colonnade. Across the street was Parkton Square, and the locked gates of the Glacier Days carnival. Eggers neared the tall fence and appraised it. With one hand, he shook the chain link, and a shower of ice beads rained down on him. He tried to climb it, but in fur booties could get no hold.

Trudy crossed to the gates and went to work on the lock that held the chain. "This is just a combo lock, like the kind for your school locker," she said. "It would be easier if I had my tools with me. I could just pop it open with a prybar."

Trudy knelt on the cold sidewalk and put her ear to the green-faced lock, while I looked through the fence to the dark carnival inside. From somewhere kept coming the keening of ravens, and though I couldn't be sure, I felt I saw a flash of black wings. The raven was a medium-sized bird, with a great curving beak that drove straight into a heavy brow, giving it a look of constant judgment. I can't think of many birds that were physically dangerous to humans, but to those with a guilty conscience, the raven could be a troubling omen.

"Voilà," Trudy said as the lock opened, and it wasn't until we were through the gate that the stillness of the place gave me the shivers. In the dark, all the funhouse faces were more personal, like people from your distant past. Each game seemed to stand waiting for its perfect customer, which wasn't me. The Hammer Blow sat ready for a stronger man, and the Gypsy dared me to purchase its dark fortune. In the moon, all the overdrawn devils and clowns seemed cut from maroon-and-blue plastic, and I wished someone would shut those ravens up.

Eggers led us down a stretch of midway bordered on both sides by shooting galleries. At counter after counter were rifles and pistols mounted on rods, all pointing into dark tents toward rows of bears who stood when shot, ducks who fell back into nothing, and wolves who would grab their asses and howl at the moon when plinked.

We passed darkened trailers that dealt in Indian fry bread and twin funnel-cake carts that folded up like campers, and then we came to a huge pile of the night's leftover popcorn, which had been thrown out in the snow. This is where the ravens were, pacing in the moon, gulleting down cold popcorn.

"God, I love popcorn," Eggers said. "That's one of the things I really miss."

"Maybe Doritos will come out with a popcorn-flavored chip," Trudy told him.

He said nothing, only steered us under the old roller coaster, the kind that packed up onto a couple of flatbed trailers. Its name was no longer visible, but Dragon or Sidewinder would be safe bets. Underneath, a lattice of shadows passed over our faces, and we could see the stains of oil that had dripped down the supports. When the light filtered down just right, you could make out the occasional flash of the nuts and washers that had worked themselves loose and now littered the ground.

Finally, Eggers came to a stop before a temporary corrugated shed the size of an aircraft hangar, hastily assembled on a bare parking lot. "Here we are," he said, and we all looked at the sign above the great sliding door. It read "4-H."

Inside, a single propane heater kept the room just above freezing, though the asphalt floor was certainly colder. The room was lined on both sides with pens of varying sizes, some with straw on the ground, and others with little shelters inside. Maybe half held animals. We walked down the row in the dim fluorescent lighting, stepping over the hoses that were wound everywhere to spray down the waste. A little llama came out of its shed and nuzzled up to the rail. Its pen had a large blue-and-yellow handicapped-parking icon on its floor, and the furry little guy seemed intent on sucking everyone's fingers. At the end of the room, where the heat barely reached, stood a pen larger than the others with what looked like a child's fort constructed in the back. There was a piece of masking tape affixed to the rail in front of us, and on it someone had spelled "Sir Oinks A Lot" in straggling letters.

"Oh, you're kidding me," I said. "This isn't right."

Eggers clapped twice and whistled.

Something rustled in the fort, and its tiny walls shook.

"This isn't happening," I told them. "This is a child's pet, that's a name a child would think up."

A giant brown-and-gray hog emerged from the fort, its head big as a beer keg. It was a pork-belly hog and must have weighed eleven hundred pounds. It snorted twice, and each time it exhaled, its white breath cleared circles of dust and straw from the floor. Its head floated, cranelike, from Trudy to Eggers to me.

Harder to describe than any bird is the pig. There was no animal quite like it. What defined it most were not its enormous dimensions, but the clack of its cloven feet on hard surfaces, the guttural horn of its squeal, the smack of its jowls bouncing as it walked, and the way the tugging weight of its face revealed the yellow undersides of its eyeballs. But what truly comes to mind when I think of the pig are sunsets over the river after the sky was blackened with the kerosened smoke of towering pyres of burning hogs. It's true that I haven't seen a pig in thirty years, but lately I have turned to petroglyph art in an attempt to document those events, and what I have discovered is that, despite its simple oblong shape, the pig is the most difficult figure to convey to a rockface.

Eggers bent over and touched his toes. Then he held the spear over his head with two hands, leaning forward and back, stretching side to side. Finally, he jumped up and down to get the blood going. "All in the name of science," he said.

"Wait a minute," I told him. "We should talk about this, we should realize what we're doing here. At least let's find some consensus."

I turned to Trudy for a dose of sanity, but there was a wild look in her eyes.

"No one's hunted with a Clovis point in twelve thousand years," she said.

Eggers added, "This is the hunt. This is what connects us to the ancient ones, to the lost peoples of the world."

Trudy touched my coat. "Look," she said, "I know your critics think the last chapter in The Depletionists is New Age-y, but when you say that the reason we are drawn to the artifact is to know, without judgment, the heart of another, I believe it. That's the whole reason I look at Paleolithic art. That's why I came here to study with you."

I took my glasses off and folded them. I rubbed my temples a moment.

"Okay," I said. "Okay."

"Wow," Eggers said. "We're joining the elect few."

"Yeah," Trudy added, "we're making history."

"Here you go, then," Eggers said, handing me the spear.

"Me? Wait a minute."

Eggers said, "It's your Clovis point, Dr. Hannah."

"I don't know how to throw a spear," I told him. "You're the one living in the Stone Age."

"That's right," Eggers said. "A pig gets killed with a twelve-thousand-year-old spear. Who do you think they're going to suspect? Yes, perhaps the authorities might consider the Paleolith living in the park."

"He's got a point," Trudy said.

"What was with the calisthenics, then?"

Eggers looked shocked. "We're all going to be running in a couple minutes."

I hefted the spear and watched as Sir Oinks A Lot took a lazy turn around the pen, probably looking for a newer, more comfortable place to sleep.

"This thing's heavy," I said.

"Choke up on your grip," Trudy told me.

Eggers pointed at the pig. "Aim just behind the shoulder blade. That's home to lung, liver, and heart. You'll get at least two out of three."

I took an extra puff off my inhaler, for luck, then backed up a couple of steps, then a couple more. I don't know why, but I scratched the soles of my shoes, one at a time, on the asphalt. I wiped a hand on my pants. The pig started to circle, the way a dog would before lying down, and I started to time my throw.

"Don't miss, Dr. Hannah," Trudy said. "That point's irreplaceable."

I ran at the pen and thrust my arm high, but my arm wouldn't let go.

I stood there with the spear still in my hand.

The truth came to me cold and swift: I was no hunter.

"Oh, give it here," Trudy said, loosening up her shoulders.

"Give the woman the spear," Eggers said. "She holds an all-military-school record in track and field."

"Trudy," I said, "we can't ask you to throw this spear. I'm a white male professor, and you, you know, you're an African American female student."

"Oh, Dr. Hannah," Trudy said, "you're so cute."

She took the spear from my flaccid grip, and Eggers winked at me.

Trudy hefted the weapon, felt its balance point, then raised it high.

"What's the bumper sticker?" she asked. "'You can have my spear when you pry it from my cold, dead hands.'"

The pig cocked its head curiously.

Then it happened. Trudy rotated her body and, drawing back, charged a throw that began in the ball of her foot. The leg followed, the hip lifting, rotating the torso around so the arm whipped like a sling. The spear launched, and the follow-through was complete enough that it left her facing sideways, hopping on one foot.

Almost as quickly as it was thrown, the spear crossed the pen and landed with a great thuk that opened a gaping, pleated wound, from which escaped a gurgly hiss as the lung pushed and pulled air through the puncture. The handle of the spear bobbed with the breath of the hog, and with every little movement, the blade walked itself deeper into the cavity of the chest. The pig let out one faint whine before its front legs crossed, almost daintily, and it went down, rolling to its side so that its final breaths sent up mists of blood that speckled the wall a steaming pink.

Eggers looked stunned. He climbed over the rail and walked cautiously to the pig. He leaned over it. "Holy shit," he said.

"Wait," I called. At any moment, that hog could jump up and slay us all. If one thing was constant in the history of the world, it was the notorious danger of pigs. They were the bane of early Mesopotamia, and in African folklore there is no more dangerous beast. Even the Clovis could not handle them. The Clovis eradicated the American lion, the saber-toothed tiger, and the dire wolf, but the wild boar was one of the few animals to live through that age of eradication.

Trudy joined Eggers. She was still shaking out her arm from the throw as she approached the pig. She crouched above a pool of blood gelling against the cold asphalt. She reached for it.

"Don't," I murmured. "Think of the parasites, the trichinosis, the bloodworms."

Trudy placed her palm in the blood, then, dripping, showed it to me.

"This is the first art," she said. "This is the original ink."

On the wall of the shed, Trudy drew a horizon line in red. Below it, she fashioned a circle, the sun of the underworld. Above the line, she used her fingers to make a set of antlers, pointing down. I recognized the symbol, haunting and primordial. She drove around Parkton with it painted on the black hood of her beater GTO.

Eggers pulled a flake from his game bag and cut the spear point free of the shaft. He brought it to me and placed it bloody in my hands, still warm from the pig.

"Here you go, Dr. Hannah," he said. "One Clovis point, as promised."

Then Trudy came toward me, face flushed from the cold, hands red, that great staticky blue light of death around her, and I thought, Yes. Perhaps my father's rakish thinking had infected me, but my hands were shaking for her.

"Are you ready?" she asked, and when I nodded, we all started running.

In bed that night, I woke to a roar from the Missouri as a shearing expanse of ice broke away. It sent a wake underneath the whole ice sheet, so that, when the wave reached the shore, you could hear fifty-five-gallon drums leap from the frozen grip of the river as, one by one, everyone's docks cracked free. I knew a great ice raft, large as a lecture hall, was spinning its way downstream.

I sat up in bed, and slowly, by starlight, began to make out the dark tendrils of all the silent houseplants that hung in my room. I checked my bedside table, and, sure enough, there was the stained Clovis point from earlier, right where I'd set it- beside a plaster cast of my mother's leg, removed just before she left us for good. Though I hadn't heard from her in thirty years, I felt pretty confident that, with the cast and maybe an X-ray of the break, I'd be able to identify my mother if I ever came across her.

Often when I couldn't sleep, I'd pick up that knee-high cast and trace the shape of my mother's calf, feel the shadows left by the fine bones in her feet, but tonight I reached for the Clovis point. The quartz was smooth and warm in the dark, and instead of its conjuring in my mind the story of a people older than civilization, I thought of Trudy. How natural this point had seemed in her hand, and with what kinship did she speak of its fashioner. Trudy seemed to know its song, and the shameful arousal I felt for her, for one of my students, as I replayed the way she launched that spear was eclipsed only by the horror of where it had landed.

Did the Clovis people know the glaciers were on the move? Did the dinosaurs comprehend the impending comet? Janis didn't know what the universe had in store. I heard the ice again, and imagined white rafts slowly floating down thousands of miles of river, a history of ice, and on these barges in my mind, I saw things and people, floating backward, away from me, into the dark. Our old dog Roamy was on one, and another was piled with the sagging boxes of Junior, index cards and notepads spilling into the current. I looked for Old Man Peabody, for Janis, for the father I used to know. Who floated by instead, alone on a piece of ice big enough for all of us, was my mother, frozen the way I last saw her, the way I would forever imagine her-in a pale-blue housecoat, holding a pale-blue handbag, leaning on aluminum crutches-and the farther she floated from me the less I was sure whether she was facing toward me or away. My imagination took a bird's-eye view as I attempted to follow her into the dark, flat landscape, cut only by the cold river of history. At the edge of sleep, I, too, was on the ice, riding it into darkness. I was not cold on this ice, only seized by the notion that if I floated far enough I'd ride the river back in time, back to the Pleistocene, a place where men and women lined the banks with pink spears. As I floated by, they shouted messages for me to deliver to their ancestors.

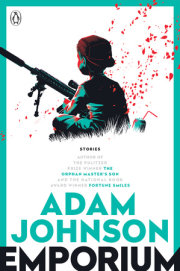

Copyright © 2004 by Adam Johnson. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.