Chapter 1

The First Stronghold

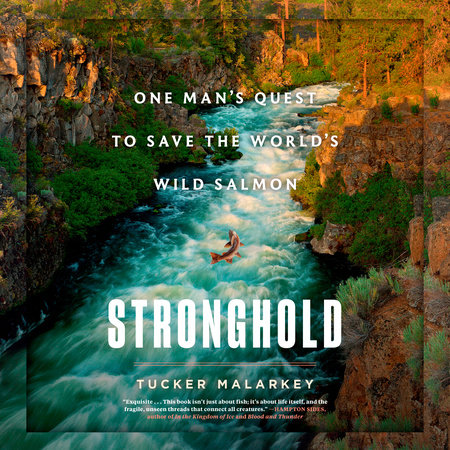

There were two fishing cabins on the Deschutes River, nestled up against the Warm Springs Indian Reservation. Guido’s family took a boat across the river and wheelbarrowed their provisions to their cabin. There were no roads on their side of the river, just miles of wilderness. The trails, mountains, canyons, draws, and creeks were part of their family mythology, a landscape both unknowable and intimate, like the river that flowed so full and strong even when they were not there, that changed every moment and changed not at all.

Here also, there were many ways to die. There were rattlesnakes coiled in the woodpile, scorpions sheltering under flat rocks, black widows spun into the corners of the boot room. None of them was as dangerous as the river itself; the river that had taken a beau of Guido’s mother and a beloved cousin, swallowed them from sight, tugging them into the whirling currents and underwater vortices.

The other cabin belonged to our family. My father and Guido’s mother were siblings, and in summers our families merged into one. There were five children in the Rahr family, and three in ours. Clustered around the same age, we were knit close in that rough country, playing games and making up stories that were too wild for most children.

Guido (pronounced Gee-doe) was the oldest of our pack of first cousins, and the only one who moved through our dangerous kingdom as if he belonged there. He had a natural grace and assurance and he rarely stepped wrong. As early as seven years old he would disappear for the day and rejoin us wordlessly, leaving us to wonder about the life he was leading, and how different it was from ours. He had been born with a natural intelligence that gave him a power we all recognized.

I tried to follow him. I was younger and a girl, but I was tough and I didn’t complain. He tolerated me sometimes, but only if I moved through the landscape as he did, mimicking his silent walk, my senses alert. I stood by as he divined where a blue racer lay resting in the shade of a sagebrush, or when he lifted a rock that harbored a scorpion. He was no more afraid of a rattlesnake than a mouse, and his quick hands could catch anything.

He told me that even with his feet on the ground, he saw the earth from far above. I believed, in some shamanistic way, that he could. I believed that from his place in the sky, the stories of the land were apparent to him: those of rock formations, springs, volcanoes, and landslides. And within these large stories were smaller ones, each as complex and complete as a miniature solar system. He could make me see these things, and so was a kind of god to me.

I could not have guessed then how close we would one day be nor, indeed, that it was even possible to be close to such a boy.

I knew in a childlike way that Guido wasn’t wired like most people. Nor was I. Since infancy, I had experienced brain tremors when for intense moments I trembled and shook and was unable to communicate. The episodes were both frightening and mysterious, for no doctor could explain why they happened. The tremors temporarily severed my connection to the world around me, and were terribly isolating. Guido was also isolated, but his was a strong isolation, and it was happy. Our slight maladaptations marked us as black sheep, the children the adults worried about most, the ones discussed in the hushed hours after dinner. But in those lonely, afflicted childhood years, Guido’s contrariety was a gift to me. When I was with him, I lost track of time. His simple, focused world delivered me from the painful vicissitudes of my own. I didn’t grasp then what an impossible child he was for his parents to raise—or how hurtful he was to the family he more or less ignored. My aunt Laurie later told me how she and Guido Sr. had struggled with a son who had no interest in learning what they had to teach him, or indeed in what the wider world considered a conventional education.

What Guido wanted, from infancy, was the freedom to pursue his own learning, unimpeded by the many adults who oversaw his life. Another world beckoned to him, and the wilder the better. When his parents denied him access to it, he ran away. By the age of four, Guido had run away multiple times to roam the fields and streams around their home in Oregon; the local police became familiar with the boy who vanished into Lake Oswego’s undeveloped swaths of suburbia, where he captured anything that moved and befriended it long enough to study it. Back in his room, he filled notebook upon notebook with renderings of insects, reptiles, and fish.

His mother was struck by the accuracy of his drawings. In preschool his precocity was noted by his teacher when she asked the class to draw what they thought their insides looked like. Most of the children drew circles filled with scribbles. Guido’s drawing had intestines and bones and organs. His teacher was so astonished she called his parents to inform them that their four-year-old had a rudimentary understanding of human biology. Laurie was mystified. The only way Guido could have known such things was by studying the family World Book Encyclopedia, and what four-year-old did that?

His first-grade teacher, Helga Peters, told Laurie that she’d never had a student like Guido; that in her experience most children were like sausages—you could stuff them full of knowledge. But Guido wasn’t like that; he knew exactly what he wanted to learn—and it wasn’t what she was teaching.

She wrote,

Guido has been the most original student during his first year in our primary grades. The academic tools, i.e. learning to read, learning to write and coping with mathematical concepts are to Guido an evil to be suffered. . . . He wants to read and write about the mysteries of nature, the creatures and the glorious wonders of creation. Although he can express himself magnificently in all art forms he is trying hard to read and to write, not easy when he has to match his excellent vocabulary. Since his speech is fast and slurred it is very hard for him to sound and spell words.

Up until this point, his parents had no idea anything was unusual about their firstborn other than that he was spirited and independent. “We didn’t know he was different,” Laurie said. “It was other people who told us he wasn’t normal.” As Guido grew older, the Rahrs began to struggle with their expectations of him. “That he simply wouldn’t cooperate came as a terrible shock to us,” Laurie remembered. Guido Sr. was bewildered by his son’s obstinacy and a character so unlike his own. The product of a genteel aristocratic German family, Guido Sr. was a pipe smoker and reader of poetry, and his love of nature ran to the romantic. He preferred fields of wildflowers to the high desert, the Alps to Oregon’s rivers, a vintage rifle to a fishing rod. The rest of the Rahr children pleased Guido Sr. greatly; they were well behaved and seemed to understand the order of things. His firstborn continued to thwart his expectations.

One time the family set off for a posh tennis camp in Arizona to polish both their children’s games and their etiquette. On their first day there, Guido failed to show up for a single tennis class. Somehow he managed to escape the compound and slink into the wilderness to see what lived in the bushes and under the rocks of the John Gardiner Tennis Ranch. He knew there were collared lizards and banded geckos. Of particular interest were the chuckwalla lizards, native to the region. These lizards did not live in Oregon, and Guido was eager to get his hands on one. When the family returned after their day of tennis, Guido was nowhere to be found. A scream issued from his mother in the bathroom when she found the bathtub filled with foot-long chuckwalla lizards.

“We couldn’t keep track of him,” his mother said. “He always had his own agenda—and we were not party to it. It was only afterwards, when it was a fait accompli, that we learned what he was up to.”

While he showed an aptitude for natural science, it was clear that something else was going on with Guido. He had an aversion to reading, and to any book that didn’t involve pictures of reptiles. Unlike his educated and literary parents, he did not enjoy school, nor did he excel in classes other than art. Midway through elementary school, Guido was diagnosed with dyslexia. Special tutors were called in and he was forcibly held to the studies he loathed. When he was released, he disappeared, melting into the woods like a spirit. In fourth grade, Guido showed a glimmer of a deeper capacity. On a hunch, his mother gave him Raymond Ditmars’s The Reptiles of North America. It was a thick, academic tome, filled with Latinate terms, scientific descriptions, and beautiful black-and-white plates and illustrations. “His eyes grew big,” she remembered. “He sat down with it right away. I think it was the first book he had ever wanted to read.” His parents watched as Guido bored into the pages of Ditmars’s guide. “It took him weeks to get through it, but he memorized it cover to cover.” Laurie Rahr was fascinated by Guido’s determination. It seemed that by sheer will, her nine-year-old son overcame his dyslexia.

Copyright © 2019 by Tucker Malarkey. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.