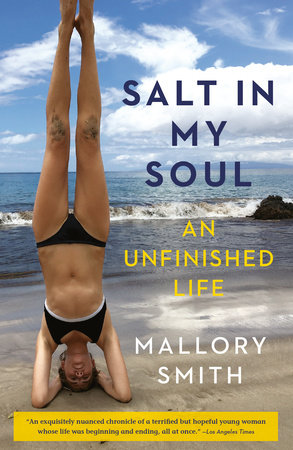

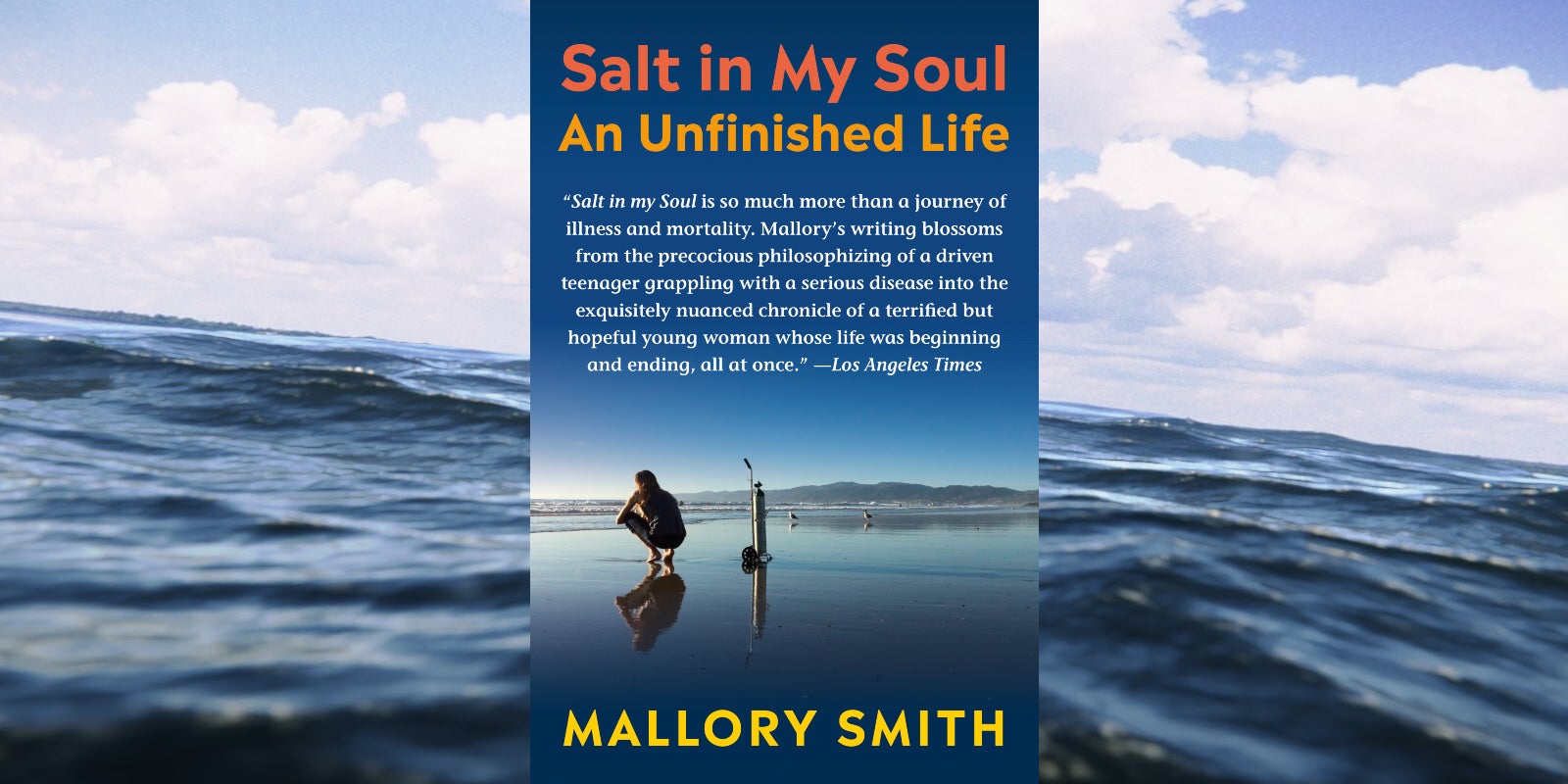

I could title my memoir Ode to Salt since salt is part and parcel of the cystic fibrosis experience. Broken proteins lead to an imbalance of salt inside and out of the cells. If you kiss or lick the skin of a CF-er, you’ll get a firsthand taste, literally, of how fundamental salt is to the disease. CF patients lose so much salt in our sweat that we can get water intoxication from drinking normal water unless we add salt to our water and our food. And salty water helps counteract some of the worst symptoms of the disease. I’ve noticed the healing effects of salt water since I was a little girl, swimming in the ocean in Southern California and on the many, many family trips we took to Hawaii for my health. I feel as if there’s salt in my soul. —Mallory Smith

I have big dreams and big goals. But also big limitations, which means I’ll never reach the big goals unless I have the wisdom to recognize the chains that bind me. Only then will I be able to figure out a way to work within them instead of ignoring them or naively wishing they’ll cease to exist. I’m on a perennial quest to find balance. Writing helps me do that.

To quote Neruda:

Tengo que acordarme de todos, recoger las briznas, los hilos del acontecer harapiento (I have to remember everything, collect the wisps, the threads of untidy happenings). That line is ME. But my memory is slipping and that’s one of the scariest aspects about all this. How can I tell my story, how can I create a narrative around my life, if I can’t even remember the details?

But I do want to tell my story, and so I write.

I write because I want my parents to understand me. I write to leave something behind for them, for my brother Micah, for my boyfriend Jack, and for my extended family and friends, so I won’t just end up as ashes scattered in the ocean and nothing else.

Curiously, the things I write in my journal are almost all bad: the letdowns, the uncertainties, the anxieties, the loneliness. The good stuff I keep in my head and heart, but that proves an unreliable way of holding on because time eventually steals all memories—and if it doesn’t completely steal them, it distorts them, sometimes beyond recognition, or the emotional quality accompanying the moment just dissipates.

Many of the feelings I write about are too difficult to share while I’m alive, so I am keeping everything in my journal password-protected until the end. When I die I want my mom to edit these pages to ensure they are acceptable for publication— culling through years of writing, pulling together what will resonate, cutting references that might be hurtful. My hope is that my writing will offer insight for people living with, or loving someone with, chronic illness.

Cystic fibrosis is a chronic genetic illness that affects many parts of the body. It operates like this: A defective protein caused by the cystic fibrosis mutation interrupts the flow of salt in and out of cells, causing the mucus that’s naturally present in healthy people to become dehydrated, thick, and viscous. This sticky mucus builds up in the lungs, pancreas, and other organs, causing problems with the respiratory, digestive, reproductive, endocrine, and other systems. In the lungs, the mucus creates a warm and welcoming environment for deadly bacteria like Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia cepacia. The vicious cycle of infection, inflammation, and scarring that comes from the combination of viscous mucus and ineradicable bacteria leads to respiratory failure, the most common cause of death in cystic fibrosis patients.

It’s progressive, with no cure, which means it gets worse over time. The rate of progression varies from patient to patient, and is often out of our control

•••

Cystic fibrosis is a disease that does a lot of taking—of dreams, of time, of travel, of friendships, of freedom, of potential, of plans, of lives.

Sitting in a hospital bed, I’m tempted to think about all the things that have been taken from me. More than that, it’s easy to think about all the things I want for my future that might no longer be possible, the will-be-takens.

I was diagnosed at the age of three. As a kid, I made plans; I loved getting in bed at night because I had the opportunity to fantasize uninterrupted about whatever I was excited about. Some of what I thought about had to do with the future: where I would choose to live later in life, places I wanted to travel to, what I might be like as a teenager and then as an adult. Mostly, I envisioned other parts of the world—back then, anywhere was better than Los Angeles. The foreign always transcended the familiar. The unknown was brimming with possibility, while the known was full in a less satisfying way; like a big glass of a clumpy protein shake, you know it’s good for you but it doesn’t rock your world: daily routines, school days spent reading textbooks, long medical treatments I didn’t want to do. As Dr. Seuss says, “You’re off to great places! Today is your day! Your mountain is waiting, so . . . get on your way!” I believed wholeheartedly in those great places to come.

Copyright © 2019 by Mallory Smith. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.