Introduction

Looking Beneath the SurfaceWe use clocks to know what time it is. Between the invention of hourglasses and digital clocks, there were analog watches—watches with hands and faces—which were the main devices we used to measure time.

Along with learning the ABCs and how to ride a bike, you probably learned to tell time using an old-fashioned clock. You might not have thought much about learning to tell time since then. It’s easy to take a skill for granted once you’ve mastered it. It becomes second nature, which is good because that allows you to focus attention on other things. Instead of thinking, “I can tell time!,” you look at a clock and think, “Only fifteen minutes until I am out of this class!”

Back then, you had to learn how to interpret the clock’s two “arms”—the little arm that measures hours, the big arm that measures minutes—in relation to the numbers, from one to twelve, on the clock’s circular background. You had to learn, for example, that when the big hand was on the twelve and the little hand was on the three, it was three o’clock. Learning to tell time was all about understanding the relationship between the clock’s hands and numbers. Once you understood that, you knew how to tell time.

In your lifetime, you’ve probably seen these types of clockfaces on wall clocks and on wristwatches. You’ve also witnessed how digital technologies have made it easier to tell time. Instead of having to make sense of the hands on the clock, we just read the numbers from digital displays on our smartphones, or on our computers, or in our cars. You may even be able to call on digital assistants such as Alexa or Siri to tell you what time it is.

But what if the clock breaks and you want to fix it?

Or what if you are just curious to know more about why the clock works the way it does? Then you need to know more than how to tell time; you need to learn how to look beneath the surface of the clock’s face, to observe and understand the mechanisms that drive the motion of the clock’s hands.

Telling time is one thing; understanding how the clock works is something else.

Wait a minute here, you may be thinking, I thought this was a book about media literacy (whatever that might be…). What’s all this about clocks and learning to tell time? Put another way: What can a clock teach us about media and media literacy?

You do not need to understand how a video is produced to enjoy YouTube, or how news is reported to read the New York Times, or how algorithms work in order to post content on Facebook, Instagram, or TikTok. Each of those activities is sort of like telling time: you can do them without much background knowledge. But if you want to understand why and how YouTube, the New York Times, or your favorite social media platform highlights some people, topics, and ideas while rendering others all but invisible, you need to know more. You need to look beneath the surface to understand the hidden but real mechanisms that shape media content and influence how we interpret it.

Critical Media LiteracyWhat interests us, the authors of this book, is a concept known as critical media literacy. Critical media literacy (or CML, for short) addresses these typically concealed, but always powerful, inner workings. Critical media literacy gets into the hidden mechanics that drive our mass media of news, information, and entertainment. CML education is a way to learn about the world, especially the world of media. According to statistical research, people around your age spend more than eleven hours a day with some form of media—and usually, you are media multitasking—that is, using more than one tool or technology at once.

Given that you spend so much time with so much media, we believe you deserve to have a robust understanding of how that media works. That’s why we think this form of knowing is especially important today.

Critical media literacy is about asking questions more than it is about learning the right answers. Through CML, we not only explore what we know but also ask how we know it. We explore what we like, what we believe, and why. When practicing CML, we employ a collection of skills that help us move from being passive consumers of media to becoming engaged critics and creators.

Meaning, Access and Representation, and ValidityThroughout The Media and Me, we will develop the themes of meaning, access and representation, and validity. These ideas are so important to understanding the media that we want to introduce them here. Reflecting back on the clock metaphor that opened this chapter, meaning, access and representation, and validity represent the inner workings, or gears, of media literacy. Examining them will help us understand how and why media institutions operate the way they do.

Meaning is the most slippery of the terms because it is so fundamental to everything we do. In an influential article from 1973, the anthropologist Clifford Geertz used the examples of blinking and winking to get at the idea of meaning. Both actions involve what we might describe as “rapid movement of the eyelid over the eye,” but you do not need to be some famous social scientist to know that winks are different from blinks. If you get a speck of dust in your eye and your eye twitches, you do not necessarily attach any meaning to that action. You’re just blinking. But when you wink at your friend, that same eyelid movement could mean anything from “just kidding” to “I am flirting.” Being able to tell blinks from winks depends on making sense of what we know and how we know it. And if that wink is going to work, all of this interpretation has to happen very quickly.

We attach meaning to actions, so gestures and body language allow us to communicate without words. But this does not mean that everyone always agrees about what something means. Because meaning is subject to interpretation, and our perspectives can vary, people sometimes have different interpretations about what something means. Think of the color red. In some contexts red is associated with passion, or love; in other situations red might convey heat; and when someone says they’re seeing red, that can mean they’re angry. The basic point is that meaning depends on interpretation, and interpretations can vary from person to person and from group to group depending on context.

Asking questions about meaning is one way to begin developing a critical stance regarding media. How do you make sense of the imagery in your favorite TV show or video game or YouTube video? What is its message? Of course, meaning is conveyed through language too. So whether we’re talking about a poem or a news story, we can ask how an author’s choice of words conveys meaning, and how different readers might interpret the author’s word choice in significantly different ways. Because critical media literacy depends on interpretation, meaning is a concept we’ll come back to again and again.

Access and representation are also basic concepts for understanding media more fully. Access opens up questions about who is included and who is excluded. As we’ll discuss in later chapters, access can be as simple as whether or not you have a computer with an internet connection. Representation can have two meanings. (Hey, there’s that concept of meaning coming up again already!) First, representation can refer to the way that images and texts reconstruct, rather than reflect, the original sources that they represent.

For anyone interested in media, this type of representation is very important. A photograph—whether it’s a social media post about a tropical vacation or a news photograph of a public demonstration—is not equivalent to the sensory experience of the sun, the sand, and the breaking waves on that beach, or what it feels like to march alongside dozens of other people down the middle of a public street where police with batons block the way forward. Asking about representation reminds us, “The map is not the territory.”

Representation has a second important meaning for people interested in media. We can ask questions such as “Who is represented?” and “How are they represented?” Examining representation in this sense encourages us to think not only about individuals but also about groups and categories of people. In this usage, representation alerts us to issues of difference and, potentially, inequality. For example, how often do news stories actually include people who are poor—not just as the invisible subjects of reports about poverty, but as actual living people who have ideas, concerns, and aspirations of their own? Questions like this link representation and access: a concern for access can lead us to look beneath the surface of media content, by asking who is included and put at the center of stories, and who is excluded or marginalized. Chapter 4 will investigate representation in more detail to examine how our identities are both shaped by and shown in the media.

Validity is the quality of being legitimate or genuine. If you say that some claim is valid, that means you have reason to believe it is true. The emphasis here should be on the phrase “reason to believe.” A claim is not valid because you say it is so; instead, it is valid because you can provide evidence to justify it—and you can defend the claim even in the face of counter-evidence.

Think of validity as a kind of solid footing. When we adopt a critical stance toward media, we ask questions about meaning—and meaning, as we have seen, is open to multiple interpretations, including competing interpretations. This situation might be enough to make you throw up your hands in despair and say, “Who cares? It’s all just a matter of opinion in the end.” This is when validity, and a host of principles that can help give us confidence that a statement or story is true, come to the rescue. Some differences of interpretation are a matter of opinion. But many differences in interpretation can be resolved by considering the evidence for and against each of the competing interpretations. For example, you and a friend may disagree about how good a musician is. Your disagreement may be solved by saying it is a difference of opinion. However, you may be able to point to the singer’s musical training, or how many top hits they’ve had, to illustrate that they have a certain level of ability that deserves consideration. Asking questions about validity helps to distinguish facts from opinions. Validity is also a core idea in critical thinking, a topic that we take up in more detail in chapter 2.

How Media Literate Are You?In 2016, the Stanford History Education Group (SHEG), a group of researchers from Stanford University, released the findings of their two-year study of how well young people evaluate and interpret information found on the internet. Based on the findings of the SHEG research, young people are not media literate. The study’s participants included students from middle school through college, all of whom had trouble telling the difference between news and advertisements, recognizing point of view or bias, and identifying who owns or runs certain websites. What the SHEG researchers determined was that young people spend a great deal of time with media but do not know how it works. Young people are adept at making use of media, but not necessarily great at evaluating it. Young people make active decisions about their media of choice, but some do not know much beyond what they see on the screen. The researchers found that many young people do not know how to analyze what is “behind the scenes,” including what many scholars call the “means of production.” Drawing from our opening narrative, we might say that the SHEG researchers found that a lot of young people know how to tell time—but they do not know how the clock works.

Do not be discouraged by this! This book will help you be part of a shift away from the dilemma that this research describes! And it’s not your fault. Do adults do much better? We all have a responsibility to teach ourselves and each other CML. In the pages that follow, you will help flip the script and develop an enhanced understanding of media literacy.

Inside The Media and MeHopefully by now you are fired up and ready to dive in. We are not interested in making you turn off the media that you use, or denying you the pleasure and joy that the media can provide. We like media too! What we want is to provide you with some ways to be a critically media-literate citizen rather than merely a consumer of media. A critically media-literate citizen is a person who accesses, analyzes, evaluates, creates, and acts with media to empower themselves and others.

That term—“critically media-literate citizen”—is an important one, but it’s also a mouthful. From here on, we’ll simply say media citizen; what we mean is a person who engages their critical media literacy skills when they use media.

Media citizens reflect on how they are using media. Most importantly, media citizens think critically about the media they use. To be critical does not mean to dislike. We can be critical of something and find great joy in it simultaneously.

In fact, sometimes thinking critically about something increases our enjoyment of it! To be critical is to take a step back from the media content we consume in order to examine it more thoroughly. This book will help you begin to look beneath the surface and challenge media narratives.

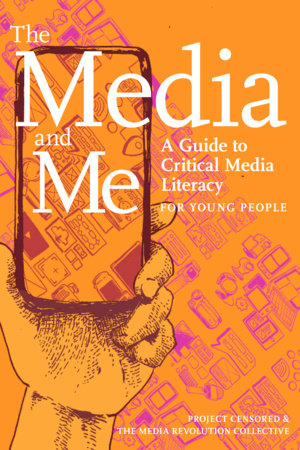

Chapters 1 and 2 examine in more detail the foundations of critical media literacy, including a close examination of how the media industries are organized and the elements of critical thinking. Chapter 3 distinguishes critical media literacy from other types of media literacy. Critical media literacy focuses on the role of power in shaping the production, distribution, and interpretation of media. Chapter 4 focuses on representation in the media, with attention to the puzzle pieces that make up our identity, including our race and ethnicity, gender, sexuality, language and accent and dialect, ability, economic class, and family structure. Chapter 5 puts the emphasis on critical media literacy. If the term “literacy” typically refers to the ability to read

and write, then what does media literacy involve? Chapter 6 focuses on the pervasive influence of advertising and the taken-for-granted culture of consumption. Chapter 7 directs attention to news and journalism. This chapter encourages a deeper look at the popular topic of news “bias” by showing how economic interests, political interests, and journalists’ reliance on official sources all impact the construction of news stories. The last chapter of The Media and Me is about putting what you’ve learned from the book’s previous chapters into action. We do not just want you to read this book; we hope that reading it will inspire you to get involved. Finally, The Media and Me ends with a glossary of key terms and concepts and suggested readings, if you want to investigate further the ideas presented in this book.

Critical thinking means asking questions that encourage us to rethink assumptions we might otherwise have, and searching for evidence to support the positions we hold. We will address how to ask purposeful questions, build sound arguments, recognize fallacies or mistakes in reasoning, determine what constitutes evidence, and raise awareness about the many biases that can invisibly but significantly shape our perception of the world.

We will examine the role of media in the lifelong process of socialization—how we learn values and a way of life from those around us. We will consider how media content, from music videos and movies to social media streams and news broadcasts, are specific forms of one fundamental human activity, storytelling. We examine how media are fundamental not only to the communication of information but also to collaboration among people and the creation of community. We also consider how economic interests shape the media you consume, by looking at the connection between media ownership and media content. We will introduce a powerful framework—known as the encoding-decoding model of communication—for examining how media messages are produced, distributed, and interpreted. If you are interested in changing the world for the better, the encoding-decoding model will likely thrill you.

Who We Are and How We Wrote This BookWe are a collection of ten authors, with distinct life stories and professional backgrounds. We include among us college students, high school and college teachers, activists, and scholars of critical media literacy. We’ve studied sociology, media studies, history, journalism, and education. We are male, female, gender nonbinary, heterosexual, and queer. We are working- to middle-class. We are white, Black, and Brown. We are all able-bodied. Three of us have children. Some of us are cat people, some of us are dog people, and some of us are learning to be dog people while still loving our cats. We are different people with at least one thing in common: we are committed to learning, practicing, and sharing our work in critical media literacy because we think it is vitally important.

In writing this book, we worked to make sure that any claim we made came with evidence. You will see that we have endnotes so that you can follow up on the sources we used in our research. Throughout the book, you will see certain words or phrases that are bolded; these are important and useful terms. You can find their definitions in the glossary at the back of the book. Throughout the text you will find “Call-Out Boxes” that give you the opportunity, if you so choose, to take some of the ideas further by doing some media analysis of your own. We envision this book as a bit of a “choose your own adventure”: you may choose to read it straight through, beginning with this first chapter, or you may choose to dip in and out of chapters whose topics particularly interest you.

Freedom of Opinion and Expression as Human Rights

In 1948, the General Assembly of the United Nations adopted and proclaimed the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, defining standards to recognize and protect the dignity of all human beings. The Declaration includes a preamble and thirty articles that specify rights that are universal and inalienable. That means people everywhere in the world are entitled to the protections they provide: You cannot voluntarily give them up, nor should anyone else take them away from you.

Article 19 of the Declaration addresses the rights to opinion and expression:

Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.

The notion that it is our universal, inalienable right to “seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers” is a remarkable, perhaps revolutionary, claim. The idea that this right extends “regardless of frontiers” might sound like something from science fiction. Indeed, back in 1948, when the original members of the United Nations established the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the technology to seek, receive, and impart information “regardless of frontiers” was pretty limited compared to the power of our contemporary means of communication.

But what inspires us about Article 19 is not how much technology has developed since 1948, although those changes are amazing. Instead we conclude this first chapter by introducing freedom of opinion and expression as fundamental human rights because this idea drives all the work that we do.

Think of the ideals expressed in Article 19 as being like the master gear in the clock that we considered at the start of this chapter. The rights to expression and opinion provide the energy and drive for all the other mechanisms that make the watch work and allow us to tell time. Freedom of expression and opinion are so fundamental that we cannot even imagine critical media literacy without them. What, after all, is the point of understanding how media work if you cannot use them to form and express opinions of your own?

Of course, just because an organization such as the United Nations asserts that freedom of opinion and expression are universal, inalienable rights does not mean this is automatically true for everyone everywhere. You probably do not need to read any further in this book to think of ways that corporations, governments, or perhaps even people you know actually interfere in ways that contradict the ideals expressed in Article 19.

The gap between the ideals expressed in Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the reality of the world we live in also inspires us to pursue critical media literacy. Critical media literacy gives us a way to assess that gulf and to figure out how to bring the actual world a little bit more in alignment with the lofty vision of a world in which everyone is free “to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.”

Copyright © 2022 by Ben Boyington. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.