“It is worth noting,” Nadya said, lecturing at a conference, “that punk feminist art is being produced in Russia today. Here is an example,” she continued, improvising. “The Pisya Riot collective works in a great variety of genres, including both visual and musical compositions.”

Pisya is a kid’s word for genitals of either sex; it is most like “wee-wee” or “pee-pee.”

Being a fictional group, Pisya Riot could not write its own music. Neither of the real-life members of the phantom group could; Nadya had taken music lessons as a child and had not done well, and Kat had no musical background. So they borrowed a track from the British punk group Cockney Rejects and used a handheld Dictaphone to record their lyrics over the sampling:

You are sick and tired of stinky socks,Your daddy’s stinky socks.

Your entire life will be stinky socks.

Your mother is all in dirty dishes,

Stinky food remains in dirty dishes.

Using refried chicken to wash the floor,

Your mother lives in a prison.

In prison she’s washing pots like a sucker.

No freedom to be had in prison.

Life from hell where man is the master.

Come out in the street and free the women!

Suck on your own stinky socks,

Don’t forget to scratch your ass while you’re at it,

Burp, spit, drink, shit,

While we happily become lesbians!

Envy your own stupid penis

Or your drinking buddy’s huge dick,

Or the guy on TV’s huge dick,

While shit piles up and rises to the ceiling.

Become a feminist, become a feminist

Peace to the world and death to the men.

Become a feminist, kill the sexist!

Kill the sexist and wash off his blood.

Become a feminist, kill the sexist!

Kill the sexist and wash off his blood.

They found they liked being Pisya Riot. Maybe they even really wanted to be Pisya Riot. To become a punk rock group, though, they would need musicians. They thought of N, a woman Nadya’s age who had come to Voina, an art group to which Nadya and her husband, Petya, had belonged. Nadya sought her out. N found Nadya changed: “In Voina, she had been this chubby-cheeked child, and now her cheeks had thinned and her voice took on a certainty. She had chosen her issues, and she may even have chosen them at random, but now she was serious and her topics were LGBT and feminism. And the choice had changed her: she no longer saw herself as an appendage to Petya and [fellow Voina member] Vorotnikov, even if she had once been a willing appendage. It had still limited her. When you are with someone, you are not flying through the cosmos, because your soul always has its home in another person—you may need it sometimes, but it is limiting and it keeps you from taking flight. Nadya got this at some point and took flight.” Pisya Riot, on the other hand, seemed to N almost pure silliness, but she envied whatever it was Nadya felt. She took on the music.

They would need other participants too, but that did not seem like a big issue; what they had in mind could be done by three or five or seven or eleven people, and there were friends and students to be recruited. They also needed a stage. At first, playgrounds, with their platforms and slides, looked pretty good. They had recorded “Kill the Sexist” at a playground. It was raining. It was also night time, which meant there were no children at the playground, but there were beer-drinking and cigarette-smoking young people, who grew concerned when they heard young women screaming their heads off about stinky socks.

They said, “What happened? Did someone hurt you? Do you need help? ”

Nadya and Kat had said, “Don’t worry, we are just making a record.” But now that they were planning on making videos, they needed a different stage, something more spectacular. One day, as they got off the Metro, they spotted it: some stations had towers made of scaffolding, with platforms at the very top, for changing light bulbs or painting ceilings, or performing punk rock, perhaps. Moscow Metro stations are, for the most part, grand architectural affairs, all marble and granite and ostentatiously spanning arches and dramatic lighting; they look like classical concert halls, and the crude scaffolding towers, viewed from the right angle, look very much like a punk affront of a stage.

They performed a number of reconnaissance missions and identified several stations where the towers were particularly tall and well placed, which is to say, placed close to the center of the hall. Then they began rehearsing. If they were going to be a feminist punk rock group, they were going to have to have instruments—Kat picked up a bass—and they were going to have to climb up the tower and unpack their instruments and mics and amplifier and take up positions fast, faster than the Metro police knew what was happening.

They practiced at playgrounds.

As they rehearsed, it became clear they needed staging and visuals and costumes. “Because if we just got up there and started screaming, everyone would think we were stupid,” Kat explained to me. “Stupid chicks just standing there screaming.”

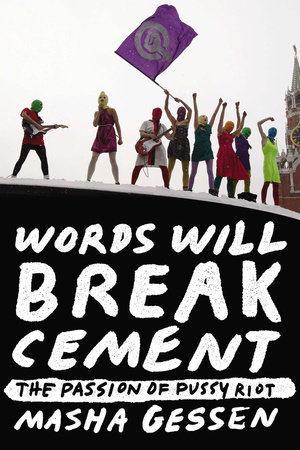

First they came up with wearing balaclavas, which would make them anonymous—but not like Russian special forces, who kept their identities hidden behind black knit face masks with slits for the eyes and mouth, but like the opposite of that: their balaclavas would be neon-colored. Then they would need dresses and multicolored stockings, to show that the whole getup was intentional. Bright, exaggerated makeup showed surprisingly well through the slits in the balaclavas. And the pillow—the pillow appeared because parliament members had begun talking about banning abortion and Putin kept talking about Russia’s so-called demographic problem, by which he meant that Russian women were not getting pregnant often enough, and so Nadya stuck a pillow under her green dress. And then she tried taking it out during the screaming, or the singing, and ripping it open. The feathers created a sort of snow effect, in addition to the birth effect and the abortion effect. That worked.

They spent a month filming their first clip. There was one time they climbed atop a Moscow electric bus and performed—it turned out the feather-letting worked outdoors as well—but mostly they filmed at Metro stations, as many as fifteen of them in all. A couple of times, they got detained. Once, Tasya, who was filming, got beaten up by police. This was before many Russians came to think of being beaten up by police as a regular part of their existence. There was the time when the police tried to beat up Petya, and Nadya wedged herself between him and them and literally shielded him with her body, and there was probably no one, not even Nadya, who appreciated the beauty of her doing this after screaming about stinky socks and penis envy.

And there was the time when the police called Kat’s father, Stanislav Samutsevich. “They would not let me see them,” he recalled. “They were in a holding pen. I had a conversation with two interesting young men. They talked to me about contemporary art and activism. I asked them who they were, and they said, ‘We are art critics in civilian clothing.’ “ It was an unfunny joke that Stanislav Samutsevich did not get: “art critic in civilian clothing” was a term used to denote KGB agents whose job it was to inform on dissidents in the Soviet Union; just like their predecessors in the 1970s, Pisya Riot had developed a following among these “art critics” before the broader public ever heard of them. That is, the secret police had literally started following them around—there were more of them with each consecutive taping.

Stanislav Samutsevich would not have known, or wanted to know, anything about dissidents in the Soviet Union, or about those whose job it had been to spy on them or jail them. “So I shared with them my views on contemporary art.” What were they? “Well, I am an old man.” The ones in civilian clothing were more knowledgeable about contemporary art. “The girls had really wreaked havoc there and the police didn’t know what to do with them. Then a big police vehicle came for them and Yekaterina told me to go home. She came home later, on the last train. I had a talk with her after that, but I am a dinosaur and I don’t understand anything about anything, so that was the last time she ever told me anything.” From that point on, Stanislav Samutsevich learned about performances from the media—or from police. He did try to protect the girls from themselves. “One time they were in the hallway, painting posters of some sort, and I came out and said to them, ‘Look, you’ve already been to the police station once, and no one knows how things could end.’ Nadya stopped coming over to the house after that.”

After that particular detention, the media got wind of the tower climbing and the screaming and the feathers flying in the Metro. They assumed Voina was back in action. Petya and Nadya were invited to the studios of the lone independent cable television channel. They denied it had been a Voina action. They said they had been detained while attending a performance of a new, different art group. They said it was called Pussy Riot.

Copyright © 2014 by Masha Gessen. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.