Praise for The Good Food Revolution

Featured on CBS Evening News, CNN, Fox News, The Colbert Report, Tavis Smiley, and NPR’s To the Best of Our Knowledgeand The Splendid Table

Goodreads Choice finalist for best food book of the year

2013 NAACP Image Awards nominee for autobiography / biography

“[Allen’s] book could have been another look at the problems of the industrial food system, the lack of healthful food in many poor communities, and ideas to reverse course. And it is that, but it’s also told through the painful but important lens of the African-American experience.

“Allen gives readers the personal, moving account of a man whose family became part of the last century’s great migration of African-Americans out of the South. Of a man who traded a successful—and not too difficult—life in the corporate world for the economic uncertainties and the nonstop labor of a small farmer.”

—Los Angeles Times

“Will Allen, the CEO of Growing Power, is teaching us how to feed a nation—naturally…. His story is not only compelling but a treatise on how our country supplies food and how the absence of a grocery store in your ’hood is no excuse for not finding a way to feed your family good food.”

—Ebony

“[A] well-written, fascinating, and truly inspiring memoir about hope and resilience through agriculture.”

—Serious Eats

“Will Allen’s life proves that success often grows from failure.”

—The Bay State Banner

“Mr. Allen has written both a touching autobiography and a compelling history of this country’s dynamic food landscape.”

—Handpicked Nation

“What [Will] Allen does with a small plot of land and a lot of determination is nothing short of inspiring….A moving story of one man’s success in producing healthy food for those who need it the most.”

—Kirkus Reviews

“From the plots of his Milwaukee urban farm to low-income communities across America, Will Allen has shown us a new type of heroism. Through The Good Food Revolution, Allen recounts his effort to reclaim his family’s heritage and, in doing so, confronts lingering disparities in racial and economic justice. As the champion of a new and promising movement, Allen is skillfully leading Americans to face one of our greatest domestic issues—our health.”

—President William Jefferson Clinton

“Far more than a book about food, The Good Food Revolution captivates your heart and mind with the sheer passion of compelling and righteous innovation. Wow!”

—Joel Salatin, author and farmer at Polyface, Inc.

“Will Allen is a hero and an inspiration to urban farmers everywhere. Now, with The Good Food Revolution, we learn how Allen rediscovered the power of agriculture and, in doing so, transformed a city, its community, and eventually the world—with the help of millions of red wiggler worms. Told with grace and utter honesty, I found myself cheering for Allen and his organization, Growing Power.”

—Novella Carpenter, author of Farm City and The Essential Urban Farmer

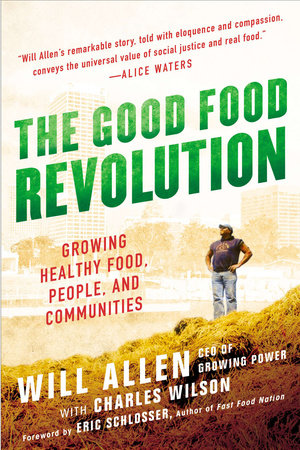

“Will Allen’s remarkable story, told with eloquence and compassion, conveys the universal value of social justice and real food.”

—Alice Waters

After retiring from professional basketball and executive positions at KFC and Procter&Gamble, Will Allen became CEO of Growing Power. He lives in Oak Creek, Wisconsin.

Charles Wilson is a journalist as well as the coauthor with Eric Schlosser of the #1 New York Times bestselling children’s book Chew On This: Everything You Don’t Want to Know About Fast Food.

THE

GOOD FOOD

REVOLUTION

Growing Healthy Food,

People, and Communities

WILL ALLEN

with Charles Wilson

To Cyndy, Erika, Jason, and Adrianna, who braved this journey with me, and to my parents, Willie Mae and O.W., whose wisdom helped guide the way.

In dirt is life.

GEORGE WASHINGTON CARVER

FOREWORD BY ERIC SCHLOSSER

ESCAPE

RETURN

PROMISES

TRIAL BY FIRE

PART 1 * ROOTS

BLACK FLIGHT

BEGINNING

A SNORTING TERROR OF

RIPPLING MUSCLE

GUESS WHO’S COMING TO DINNER

BACK TO EARTH

PART 2 * SWEAT EQUITY

BLACK GOLD

A LITTLE HOPE, A LOT OF WILL

HOMECOMINGS

PART 3 * THE REVOLUTION

OVERNIGHT SUCCESS

NEW FRONTIERS

THE DREAM

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

CREDITS

NOTES

BOOK CLUB / STUDY GUIDE

FOREWORD

By Eric Schlosser

Any discussion of race in American society seems, increasingly, to be taboo. The election of an African American president has led many to argue that the color of a person’s skin has become irrelevant, discrimination is a thing of the past, and we now live amid a post-racial culture. In my view, that’s wishful thinking. A long list of contrary arguments can be made—but the most useful, in this foreword, would be to mention how this country has, since its inception, produced its food. The history of agriculture in the United States is largely a history of racial exploitation. From the slavery that formed the rural economy of the South to the mistreatment of migrant farm workers that continues to this day, our food has too often been made possible by someone else’s suffering. And that someone else tends not to be white.

Will Allen knows this history all too well. His family lived it. His parents escaped sharecropping, the form of servitude that replaced the plantation system after the Civil War, and like millions of other African Americans, they fled north. Their Great Migration was often an attempt not only to seek a better life in the city, but also to leave behind the rural customs and trappings and mindset associated with centuries of hardship and pain. The great tragedy for many African Americans, as Allen explains in this book, is that in losing touch with the land and with traditions handed down for generations, they also lost an important set of skills: how to grow and prepare healthy food. By heading north they frequently traded one set of problems for another.

It’s no coincidence that the epidemic of diet-related illnesses now sweeping the country—obesity, diabetes, high blood pressure, heart disease, strokes—are harming blacks the most. They are more likely to be poor, to live in communities without supermarkets, farmers markets, or produce stores. But their neighborhoods are crammed with fast food restaurants, liquor stores, and convenience stores selling junk food. These are toxic environments when it comes to finding healthy food. Industry apologists like to argue that our decisions about what to eat are the result of “personal responsibility” and “freedom of choice.” A recent study in Southern California contradicts that sort of argument. It found that a person’s life expectancy can be predicted on the basis of his or her zip code. The wealthy in Beverly Hills are likely to live ten years longer than the poor in South Central Los Angeles. It’s hard to place the blame solely on your personal choices, when life expectancy can be determined in large part by something that none of us can control: the neighborhood in which we were born.

Today the two leading causes of preventable death in the United States are smoking and eating too much unhealthy food. When both of those habits became unpopular among the white, well-educated, upper-middle class, the companies that sell cigarettes and junk food focused their marketing efforts on African Americans, people of color, and the urban poor. Long after smoking was linked to cancer and heart disease, the tobacco companies aggressively sought new customers in minority communities. An internal marketing memo by an executive at Brown&Williamson, the company that once sold Kool cigarettes, explained the industry’s thinking. “Clearly the sole reason for B&W’s interest in the black and Hispanic communities is the actual and potential sales of B&W products,” he wrote. “This relatively small and tightly knit minority community can work to B&W’s marketing advantage, if exploited properly.” Thanks to that sort of thinking, and the cigarette advertising that has flooded African American communities, the lung cancer rates among blacks are much higher than among whites. As the fast food chains pursue a similar strategy, disproportionately marketing their products to African Americans and fueling the obesity rate in low-income communities, the health disparity between blacks and whites continues to grow.

At Growing Power, the organization led by Will Allen, you will find a completely different sort of mentality. Instead of trying to earn profits by harming the poor, it hopes to create an alternative to the nation’s centralized industrial food system. It’s working to teach people how to grow food, cook food, and embrace a way of living that’s sustainable. Allen has transformed a dilapidated set of greenhouses in downtown Milwaukee into the headquarters of an urban farming network that now operates in seven states. He has developed innovative methods of growing fruits and vegetables, of producing fish through aquaculture, and of using earthworms to transform waste products into fertilizer—all in the heart of a major city. To say that Allen’s thinking is unconventional would be an understatement. But that’s what has made him a pioneer of urban agriculture and a leader in today’s food movement. He understood, long before most, that America’s food system is profoundly broken—and that a new one, locally based and committed to social justice, must replace it.

The new farming techniques being perfected at Growing Power are not yet reliably profitable. This fact does not diminish their importance and must be viewed in a larger perspective. America’s current agricultural system was hardly created by free market forces. Between 1995 and 2011, American farmers received about $277 billion in federal subsidies. And the wealthiest 10 percent of farmers received 75 percent of those subsidies. Almost two-thirds of American farmers didn’t receive any subsidies at all. In addition to getting massive support from taxpayers, the current system is imposing enormous costs on society—costs that aren’t included on the balance sheets of the major fast food and agribusiness companies. Last year the revenues of the fast food industry were about $168 billion, an impressive sum. But estimates of the cost of foodborne illnesses in the United States and of the nation’s obesity epidemic, as calculated by researchers at Georgetown and Cornell universities, are even higher. Those two costs alone add up to about $320 billion. By any rational measure, this industrial food system isn’t profitable or self-sufficient. Although Growing Power receives foundation grants, it’s creating a system that will be sustainable. And the good that Growing Power’s doing in the communities it serves—the heart attacks and strokes and hospital visits it helps people to avoid, the sense of empowerment it gives, the families it brings together—represent a form of social profit that’s impossible to quantify.

This book tells Will Allen’s story and lays out his farming philosophy. Instead of running from the past or trying to deny it, Allen has confronted the dark legacy of slavery and sharecropping. He has tried to reconcile the rural and urban experiences of African Americans, imagining a future that can combine the best elements of the two. He has spent years working among the poor, preaching a message of compassion and self-reliance. I admire what Will Allen has achieved. And I hope others, many others, will soon follow in his path.

Willie Mae Kenner

ESCAPE

She held a one-way ticket.

In December of 1934, my mother, Willie Mae Kenner, stood in the waiting room for colored people at the train station in Batesburg, South Carolina. She was twenty-five years old. Her two young boys, my older brothers, were at her side. She was heading to Union Station in Washington, D.C. She was trying to escape our family’s long history in agriculture.

I imagine her on this day. Willie Mae was known to be beautiful and headstrong. Many local men had called her “fine”—she had strong legs, smooth skin, a round and lovely face, and thoughtful eyes. She also had dreams that were too big for her circumstances. She and her husband, and seven of her nine siblings, were sharecroppers: tenant farmers who gave up half of the crop they planted and harvested each season in exchange for the right to pick it. It was the only life that she had known.

My mother held different hopes in her heart, both for herself and her children. She had fought to obtain a teaching degree from Schofield Normal and Industrial School, a two-year college initially set up after the Civil War by Quakers, to educate free slaves. She wanted to be a teacher. Her family noticed that when she was required to pick cotton or asparagus, she did the work without complaint. Yet she wore a long, flowing dress on top of her work shirt and pants while in the fields. It was as if she wanted to find a way to give grace and dignity to work that often provided neither.

From the train station in Batesburg, Willie Mae was trying to escape asparagus and cotton. At the time, the South was still in the thrall of “Jim Crow”: the rigid set of laws set up after the Civil War to separate whites and blacks in almost every part of public life. The 1896 Supreme Court decision in Plessy v. Ferguson—allowing “separate but equal” facilities for black people—meant that my mother could not share the same train car with white passengers. She and her children could not even wait in the same area for the train to come. Her train car sat directly behind the coal car, where men shoveled the rocks into the roaring engine. The smoke of the engine blew through the car’s windows and seeped into her clothes. She and her two boys would need to use a bathroom marked not “Men” or “Women” but “C,” for “Colored.”

Her journey was to take her to the nation’s capital, where Willie Mae planned to reunite with her husband, James Kenner. His friends called him “Major,” for reasons I never understood. He had left South Carolina after falling into debt. During the Great Depression, the price for cotton had dropped to only 5 cents a pound—down from 35 cents only a decade earlier. Major had found himself owing more to his landowner at the end of the planting season than when he began it. Sharecropping had begun to feel like slavery under another name.

“There’s no money here,” he told my mother shortly before leaving.

Major found a small place to live in Ken Gar, an all-black neighborhood on the edge of Kensington, Maryland, ten miles from the White House. He sent word to my mother to come. Major was now building houses instead of planting crops. Willie Mae had never seen the place she was going to call home.

My mother left the South before I was born. I know from relatives that she decided against boarding her departing train at the nearest station, in Ridge Spring, likely out of concern that local people would talk about her. When I was growing up, she rarely spoke of her Southern past, as if it were a secret that was best not talked about in polite company. She told my brothers and me that she liked the taste of every vegetable except asparagus—she simply had picked too much of it.

I have wondered what passed through her mind when the train pulled out of Batesburg. As the locomotive edged north out of South Carolina, she would have seen from the windows the life she had known. She would have seen the long-leaf pine trees, the sandy soil, and the fields that yielded cotton and parsnips and cabbage and watermelon. She would have seen other sharecroppers at work, their clothing heavy with sweat.

Willie Mae knew how to sustain her family in South Carolina. She had learned from her mother how to bed sweet potatoes and garden peas and cabbage and onions in the early spring. When the full heat of summer came, she had learned how to plant turnips and eggplants and cucumbers and hot peppers and okra and cantaloupes. She had learned how to take all the parts of a hog that the men slaughtered and turn it into souse (a pickled hog’s head cheese), scrapple (a hog meatloaf), liver pudding, or a dish called “chitlin’ strut”—fried pig intestines. She had learned in the late autumn how to can peaches and sauerkraut and pecans and yams for the cold season.

She was leaving for a city where it was uncertain if any of the skills she had—or any of the dreams she harbored—would matter.

All across the South, other sharecroppers were making the decision to uproot and go. My mother was only one of six million African Americans in “The Great Migration,” an exodus from the rural South to Northern cities. Of my mother’s nine brothers and sisters who were born in Ridge Spring, South Carolina, seven left from the 1930s to 1950 for a new life in New York, New Jersey, or Maryland. Her family left farming in search of dignity. They left crop rows for sidewalks. Dirt roads for pavement. Woodstoves for gas ranges.

Half a century after Willie Mae left Ridge Spring, in an unlikely development, I returned to a profession that she and her family had tried so hard to leave behind.

Will Allen

RETURN

I am an urban farmer.

The poet Maya Angelou has said that you can never leave home.

It’s in your hair follicles, she said. It’s in the bend of your knees. The arch of your foot. You can’t leave home. You can take it, and you can rearrange it.

This was true for my mother. It is true for me. My family left the South, but it never entirely left us. In a matter of three decades in the twentieth century, the Great Migration transformed the African American experience from a rural to an urban one. The generation of African Americans born in the wake of that migration—my generation—would live in a world very different from that of our ancestors. In that transition, we lost the agricultural skills that had once been our birthright.

In 1920, there were more than 900,000 farms operated by African Americans in the United States. Today, there are only 18,000 black people who name farming as their primary occupation. Black farmers cultivate less than half a percent of the country’s farmland. The question is whether this should be called progress. Most black people who left agriculture in the twentieth century did so out of economic self-interest. My mother and Major Kenner were among tens of thousands of sharecroppers who saw no future in the rural South and who often talked about their past there with shame. They wished for a better life for their children.

Some black leaders encouraged my parents’ generation to leave the land as a way of self-improvement. At the turn of the twentieth century, the great black intellectual W. E. B. DuBois had urged African Americans to find success through a liberal education.

“The Negro race,” DuBois wrote, “is going to be saved by its exceptional men.”

With this position, DuBois found himself in a long-standing argument with the educator and writer Booker T. Washington, who argued that black people would be better served by the development of practical abilities. He thought that African Americans should make an effort to improve their own position from within—by developing skills for self-sufficiency and by helping one another.

“Agriculture is, or has been, the basic industry of nearly every race or nation that has succeeded,” Washington wrote. “Dignify and glorify common labor,” he said elsewhere. “It is at the bottom that we must begin, not the top.”

DuBois’s ideas won. His vision helped give us a world where it was possible to have Martin Luther King, Jr., Jackie Robinson, Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Colin Powell, Ben Carson, John Lewis, and Barack Obama. African Americans proved their worth in corporate boardrooms, in Ivy League universities, on sports fields, in operating rooms, in the halls of Congress, and in the White House. This “Talented Tenth,” as DuBois called top-performing African Americans, provided blacks with role models and reasons for pride.

Yet there never was a place among DuBois’s Talented Tenth for farmers. And for all of the progress in civil rights in the past several decades, there is one area in which we have stepped backward. Great disparities have grown in the physical health of our people. This change has come directly in the wake of the departure of black farmers from their land.

Nearly half of African Americans born in the year 2000 are expected to develop type II diabetes. Four out of every ten African American men and women over the age of twenty have high blood pressure. Blacks are 30 percent more likely to die young from heart disease than whites. And while some suffer from the effects of too much unhealthy food, others go hungry. Almost one out of every six households in the United States will find themselves fearful sometime this year of not having enough food to eat.

These problems are not limited to one race, and they are not owing simply to faults of willpower or personal discipline. They are the symptoms of a broken food system. In inner-city communities throughout the United States, it is easier—and often less expensive—to buy a Twinkie or frosted cupcakes or a box of fried chicken than fresh vegetables or fruits. Our current generation of young people rarely eat fresh foods, don’t know how to grow or prepare them, and in many cases, can’t even identify them. They have become entirely dependent on a food system that is harming them.

I believe that equal access to healthy, affordable food should be a civil right—every bit as important as access to clean air, clean water, or the right to vote. While there are many reasons for the decline in number of black farmers, one of the most important is that they are almost always small farmers. They have suffered the same fate as other small farmers. Over the past fifty years, a new food system has helped push them off their land.

This system came to value quantity over quality, uniformity over diversity, and profit over stewardship. Farmers were encouraged to plant commodity crops like soybeans or corn from fencerow to fencerow, and to get big or get out. There was a relentless pursuit of cheapness over other values, and food came to be made by automated machines and chemical processes. Men in laboratories dreamed up foodstuffs that were calibrated with precise amounts of sugar and fat, and that were delivered to customers by airplanes and trucks in cardboard and plastic and cellophane. The farmer became less important than the food scientist, the distributor, the marketer, and the corporation. In 1974, farmers took home 36 cents of every dollar spent on food in the United States. Today, they get only 14 cents.

This is not the right path. It is endangering the health of our young people. It has brought us fewer jobs in agriculture, unhealthier diets, and a centralized control structure that has made people feel powerless over their food choices. It has stripped people of the dignity of knowing how to provide for themselves on the most basic level. It has given us two very different food systems—one for the rich and another for the poor. A large gap has opened between those who have access to nutritional education and cage-free eggs and organic mesclun greens and those whose easy options are fried chicken joints and tubs of ice cream and shrink-wrapped packages of cheap ground beef.

Food should be a cause for celebration, something that should bring people together. The work of my adult life has been to heal the rift in our food system and to create alternative ways of growing and distributing fresh food. My return to farming was a kind of homecoming. As a young man, I felt ashamed of my parents’ sharecropping past. I didn’t like the work of planting and harvesting that I was made to do as a child. I thought it was hard and offered little reward. I fought my family’s history. Yet the desire to farm hid inside me.

It hid in my feet. They wanted the moist earth beneath them. It hid in my hands. They wanted to be callused and rough and caked with soil. It hid in my heart. I missed the rhythms of agriculture. I felt a desire for the quiet of the predawn and the feeling of physical self-worth and productivity that I only felt after a day when I had harvested a field or had sown one. For a long time, I had put my faith in different values. I had sought a life in professional basketball and then in the corporate world.

In my forties, I left that life behind. I opened my own city vegetable stand, five blocks from Milwaukee’s largest public housing project. I recognized the potential I had to do much more, even as I struggled financially to keep my operation open. I wanted to try to heal the broken food system in the inner-city community where my market operated.

So I began to teach young people from the projects and the inner city how to grow food. I conveyed the life lessons that agriculture teaches. Through trial and error, my staff and I developed new models for growing food intensively and vertically in cities. We found ways to make fresh fruits and vegetables available to people with little income. We created full-time agricultural jobs for inner-city youth. We began to teach people—young and old, black and white—how to grow vegetables in small spaces and reclaim some small control over their food choices. We found ways to redirect organic waste from city landfills, and to use it instead to create fertile soil. We connected small farmers in Wisconsin to underserved markets in inner-city communities. We provided a space where corporate volunteers could work alongside black inner-city youth, hauling dirt, planting seeds, and harvesting together.

I did not anticipate how my work would grow, or how eager others would be to participate in it. Today, my urban farm produces forty tons of vegetables a year on three city acres. We provide fresh sprouts to thousands of students in the Milwaukee public school system, we distribute inexpensive market baskets of fresh fruits and vegetables to urban communities without grocery stores, and we raise one hundred thousand fish in indoor systems that resemble freshwater streams. We keep over five hundred egg-laying hens, and we have an apiary with fourteen beehives that provide urban honey. We maintain a retail store to sell fresh food to a community with few healthy options.

Our operation is far from perfect. But my staff and volunteers have become part of a hopeful revolution that is changing America’s food system. This book is my story, and the story of our movement.

The back greenhouses of 5500 West Silver Spring Drive, 1993

PROMISES

In mid-life, I had arrived at that comfortable middle-class existence that so many in the Great Migration had wished for their children.

I was forty-three years old in January of 1993. I was driving in northwest Milwaukee in a company car on a frigid Wisconsin morning. I was on a sales run for the Procter&Gamble paper division. My job was to sell paper products: cases of Charmin toilet paper and Bounty paper towels and Puffs tissues. I wore a suit and tie. My long legs—I am six-foot-seven—were crammed up against the dashboard of a Chevrolet Malibu. The car seats were flecked with stray bits of fried chicken and donut residue. I had a good salary, a nice title, a generous retirement package.

I can’t say, though, that I was happy. My adult working life had required several internal compromises. Before this job, I had worked a decade for the Marcus Corporation, managing half a dozen Kentucky Fried Chicken stores. Though I felt confident about my skills in business, my work had long felt like a project of my wallet rather than a project of my heart.

My chief competitors at Procter&Gamble were Kimberly-Clark and Scott Paper. My job required me to build good relationships with the managers of several dozen grocery stores in Milwaukee and Chicago. One of the expectations of my job was that I would maximize the “hip-to-eye” ratio of our products as compared to that of our competitors. Procter&Gamble wanted their products to sit on grocery shelves at the customers’ hip-to-eye level, where they would be seen and most easily grabbed.

I needed Luvs to beat Huggies. I needed Puffs to beat Kleenex. Procter&Gamble’s paper division kept track of how our products scored against our competition in each of my stores, and the company had several strategies to increase its market share. They asked me to try to obtain “movement numbers” from each grocery store manager. When analyzed, those numbers would allow us to see where products sold most briskly. Once I had those statistics in hand, young people in my corporate offices could go to their computers and craft a visual “planogram.” This suggested where each product in a store could be stocked to increase sales. I presented our planograms to the grocery managers, and I offered Procter&Gamble’s help resetting every item on their shelves—free of charge. I made the case in the manager’s self-interest.

“You’ve got these products here that aren’t selling,” I’d say. “You’re losing money. We’ll restock them and get this thing fixed.”

One of the essential things about the Procter&Gamble planogram was that it maximized the hip-to-eye ratio of Procter&Gamble’s own products. So while I presented the planogram as being in the store’s best interest, it was also always in my company’s best interest. Kimberly-Clark and Scott sold their own planograms, so it was a very competitive business. My rivals often didn’t like me because our company was powerful and I was often successful. One day, I heard a representative from Kimberly-Clark whisper under his breath as I passed by.

“There goes Procter&God,” he said.

He thought that I was arrogant. I didn’t care. I am a competitive man. I had stuffed myself into the shape of this job, and I was going to be true to my nature within its confines. I took some pride in the fact that I had won several sales awards. I had been responsible for one of the largest Pampers sales in the company’s history—a single purchase to a grocery wholesaler of twenty-five thousand cases of diapers. I liked my colleagues and the man who hired me. Yet there was part of me that felt empty.

On this January day, as I was driving, I had a chance sighting that would allow me to consider the possibility of another life. I was traveling west on Silver Spring Drive in Milwaukee, on my way to speak to a manager at a grocery store. The avenue was an artery that connected the tony Milwaukee neighborhood of Whitefish Bay—sometimes called “White Folks’ Bay”—with neighborhoods to its west, like Lincoln Park and Hampton Heights, that were poorer and black. The white and black communities were divided by the Milwaukee River.

I had never driven down this road before. I passed gas stations, an auto repair shop, churches, and a windowless convenience store offering cheap fried chicken. I drove past a gray Army Reserve training center. When I reached the intersection of West Silver Spring and Fifty-fourth Street, I saw a “For Sale” sign ahead of me on the right. It was painted on a four-by-four piece of plywood. The telephone number listed was a “286” number, which usually indicated a number for city government. The sign stood next to a row of greenhouses set back from the road. Those greenhouses really seemed out of place in this neighborhood. Attached to the one closest to the road was a small building—a shop?—with a concrete porch and an awning.

I tapped my brakes. I had only glimpsed the buildings for a few seconds as I passed. The sign intrigued me, though, because of an idea I had held quietly in my heart. I kept driving, slowly, and I didn’t want to be late. Yet when I saw an opportunity ahead of me to make a U-turn, I returned quickly to the facility.

As I stepped out of the car, I saw five connected greenhouses stretched back away from the street. The glass in the front greenhouse was cracked in several places. I made out the shape of flowers through the humid windows. Outside hung a faded sign that read OLDE ENGLISH GREENHOUSE. At the back of a parking lot adjacent to the greenhouses there was a small red barn that looked like it belonged in the countryside. There was also vacant land in the rear of the property and a narrow yellow duplex on the other side of a parking lot.

I could not tell if anyone was inside the greenhouses or the shop, and I decided not to check. I took down the phone number on the sign. Later that afternoon, I called and got an answering machine on the Milwaukee city government’s zoning and development committee. Through a friend who worked in real estate, I found out that the current tenants of the greenhouses and the shop were florists. They had fallen too far behind on their payments, and they were being evicted. When I finally reached someone with the city government, he asked me why I was calling.

“I am a farmer,” I said. “I’m interested in the place as a market to sell my food.”

I was leading two lives. For several years, I had crammed a one-hundred-acre farm into the gaps of my corporate job. My farm had started small, as a hobby, but it had become outsized for a man whose salaried work was elsewhere. I grew on fifty acres owned by my wife’s mother and on fifty acres that I leased in Oak Creek, Wisconsin, the town where I lived.

According to the 1990 census, I was one of only twenty-five black people in the entire state of Wisconsin to operate or manage a farm. From spring to fall, I often rose at 4 A.M. on weekdays to plant and harvest before changing clothes and heading to work. I returned home from work, changed clothes again, and watered or harvested late into the night. I was growing collard greens, curly-leaf mustard greens, slick-leaf mustard greens, turnip greens, corn, kale, Swiss chard, and tomatoes. I employed a few young people and some local Hmong farmers part-time as help.

The farm was kept alive by my own passion. I had learned the skills of planting and harvesting as a boy, from my parents. I was now growing more food than I knew how to sell. I gave much of it away to friends and family. I sold what I could out of the back of my pickup truck at weekend farmers markets. There was no significant money to be made from it. It was all I wanted to do.

When I saw the facility on West Silver Spring Drive, the place spoke to a dream I had. For the past year, I had been looking for a roadside stand to call my own.

A couple weeks after my telephone call to the Milwaukee zoning committee, a real-estate agent met me at the greenhouses. We parked our vehicles in a lot outside the red barn—the last remnant of an old farm that had once stood on that site. The agent began the tour by explaining that this two-acre plot sat in the middle of what used to be known as “Greenhouse Alley,” a flower-growing district. The road directly north of West Silver Spring Drive was still called “Florist Avenue,” though there were no longer any florists there.

As Milwaukee grew in the twentieth century, both north and west, the city absorbed the countryside. At one time, local farms had helped feed the residents of Milwaukee. Four blocks away, Wisconsin’s largest public housing complex, called Westlawn, occupied seventy-five acres and contained more than three hundred housing units. That land had once been a single family farm. When the farmers were pushed out of the area, the agent explained, the floral industry had taken its place. Eventually, that industry was impacted by the growth of a global economy. Flowers began to be imported from South America, and local flower shops most often sold roses that had been flown in from Ecuador or Colombia. The florist who owned these greenhouses was the last to survive in Greenhouse Alley.

As I walked through the facility, I saw that the roofs of his greenhouses were linked together, forming one large structure that stretched back from the road. Rusting pin nails held in the glass panes. A ragged collection of flowers, cactuses, and bedding plants filled the greenhouses. There were holes in the glass and broken shards on the floor; many of the panes were slipping. Water from melted snow had dripped inside.

I was told that children across the street occasionally threw rocks at the glass roof and walls. The current tenant had tried without success to chase them away. The real estate agent said the city hoped that the new owner might cultivate a better relationship with the community.

We walked to the back of the property, behind the old red barn. Beside the barn was a slim yellow duplex that was included in the asking price. The shingled roof looked in need of repair. The lot outside included an acre of unused land bound by a chain-link fence. The land was overgrown with weeds and tall grass.

The whole place was a mess. But I could feel its potential. I knew from my drive through the neighborhood that I would not have any competition if I were to try to sell fresh fruits and vegetables there. The only other places I saw to buy food within a mile were a McDonald’s, a Popeyes, and several convenience stores. I could provide parking on the street, and Silver Spring Drive seemed busy to me.

“I’m interested,” I said.

The agent told me I had competition. A local congregation wanted to demolish the greenhouses and build a church on the site. If they were successful, the city would lose its last parcel of land zoned for agricultural use. I needed to convince the city’s zoning and development committee that a produce stand would be better for the community than a church.

A week later, I walked into city hall. I stood up before six committee members in a white conference room.

“My name is Will Allen,” I began. “I am a farmer from Oak Creek.”

I told the zoning and development committee that I wanted to create a farm stand. I said that a Kohl’s grocery store had recently closed down the street from the greenhouses, and there was little access to healthy food in the area—despite the presence of the largest public housing project in Milwaukee. I said that it was my intention to hire local youth, as I had done in Oak Creek, where young people worked for me in the fields during the summer. I said that my three children had grown up on a farm with me and that it had taught them useful skills like hard work and self-discipline.

I continued, offering a vision of the role I hoped to play in a community I did not yet know. It was a hopeful presentation; it was also terribly naive. One of the aldermen listening on the committee was Don Richards. He had grown up on a farm in Sheboygan, a lakeside community north of Milwaukee. Don was rail thin with gray hair, and he sat silently as I gave my speech. After I finished, each committee member was allowed to ask questions. Don Richards spoke up.

“We have enough churches in our community,” he said. “What you’re planning to do is religion in itself.”

Later that week, I received a call from the real estate agent who had given me my first tour of the greenhouses. He said that the board had approved my plan if I could come up with the financing. When I heard the news, I thought of Don Richards’s faith in me. I thought his comment helped win the board’s approval. He later told me what he was thinking.

“You made all of these outrageous promises,” Don said. “I was taking a chance on you. But I didn’t want you to make any more promises you couldn’t keep.”

In 1993, my wife, Cyndy, and I had only a few savings from our nearly quarter of a century of marriage. We had paid for our son and two daughters to attend a private high school, and we were still paying for their college educations. Our daughter Adrianna, the youngest child, had recently left to attend New York University. To finance the purchase of the greenhouses, I would have to cash in my retirement savings and take out a mortgage. I knew it was a risk to abandon a secure income for something that had no guarantee of success. I felt confident, though, that I could make my business model work.

I left Procter&Gamble. From tapping out my 401(k) I obtained about $20,000 that I planned to use to cover some of my early operating costs. I would need an additional $70,000 to purchase the facility. The city recommended I turn to Firstar Bank, one of the few local banks that operated in low-income neighborhoods and communities of color. They had a branch not far from the greenhouses, at the corner of Fond du Lac and North Avenues. I had good credit at the time, and despite the novelty of the business I was proposing, I was approved without much difficulty.

Not long after I received the bank loan, I walked through the greenhouses again. The florists had trashed the place as they left—ripping out lighting fixtures and taking a generator that was supposed to have remained. There were holes in the glass that I had not seen before, and orange rust on the heating pipes.

I couldn’t fix everything. My first priority was just to get the market open quickly to generate some revenue. Over the next few weeks, I made modest repairs. I swept and washed the concrete floors, which were cracked in places. I hired the last man in the Milwaukee area who knew how to repair greenhouses to fix the glass panes that were in most danger of falling. In the greenhouse nearest the road, I decided to paint the glass white to prevent the interior from getting too hot in the summer. I wanted this greenhouse to serve as my market. I didn’t have the resources then to fix the other greenhouses, and I needed to focus on what was possible. To provide extra income, I also decided to lease out the facility’s small shop to a florist friend for $1,000 a month. She wanted to service the funeral business and to work with FTD, the flowers-by-phone retailer. She hoped that with a low overhead, she could avoid the fate of the florist who preceded her.

I set my opening day for April 3, 1993. A friend painted me a sign on a piece of plywood: WILL’S ROADSIDE FARM MARKET. My brother-in-law had some T-shirts made up. They read: BIG WILL: THE GUCCI OF GREENS. He called me the Gucci of Greens because he thought the spinach from my farm looked so luxurious, he said.

On the Saturday morning that I opened, I arrived with my son, Jason, and some friends before the sun came up. I had slept only a few hours that entire week, and I spent the night before we opened harvesting greens in the dark. I wanted my greens to be as fresh as possible. To supplement what I had grown, I ordered fruits and vegetables from other farmers. Many of those crops were Southern specialties: okra, butter beans, black-eyed peas (or “cowpeas,” as I knew them as a boy, because they were colored like a Holstein). I barked directions to my son and friends who were helping me assemble the produce on tables.

“Stack ’em high and watch ’em fly!” I said.

I’d learned about the importance of good presentation in my years with Procter&Gamble. If you provided an image that evoked a bountiful harvest—a product spilling out of wicker baskets, for instance—people assumed it had to be good.

When my friends and I finished readying the market, the sun was coming up. We prepared to open. Farming had taught me to have trust in the unseen. You plant for a harvest that you hope will arrive but that is never guaranteed. The opening of Will’s Roadside Farm Market required a similar kind of faith. I hoped it would be rewarded.

At Will’s Roadside Farm Market, soon after it opened in 1993

Yet farming had also taught me to expect the unexpected. Two days of heavy rains could wash away a crop that you had worked on for weeks. A cruel drought could choke your plants, and they would come up stunted or withered. I didn’t know yet what would become of my dream.

The back lot of Will’s Roadside Farm Market, c. 1995

TRIAL BY FIRE

I started Will’s Roadside Farm Market in 1993 for selfish reasons. In making the case for my business to the city’s zoning committee, I said that I wanted to hire youth from the community. This was true. Yet if I were to be honest to myself, my greater desire was to be my own boss.

The experience of my first two years at the greenhouses, however, began to complicate these selfish wishes. I suffered financially in ways that I had not anticipated, and I was pushed to the brink of default on my loan. At the same time, I started to see a role I could play in the community where I had opened my shop.

. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.