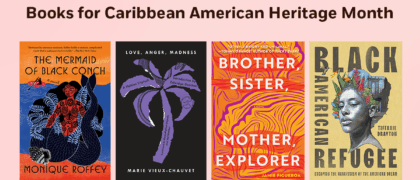

Love

Quietly, like a shadow, I watch this drama unfold scene by scene. I am the lucid one here, the dangerous one, and nobody suspects. An old maid! No husband. Doesn’t know love. Hasn’t even lived, really. They’re wrong. In any case, I’m savoring my revenge in silence. Silence is mine, vengeance is mine. I know into whose arms Annette will throw herself, and under no circumstances do I plan to open the eyes of our sister Félicia. She is too enraptured and carries the three-month-old fetus in her womb with too much pride. If she was smart enough to find herself a husband, I want her to be smart enough to keep him. She has too much confidence—in herself, in everyone. Her serenity exasperates me. She smiles while sewing shirts for the son she’s expecting, because of course it must be a son! And Annette will be the godmother, I bet . . .

I rest my elbows on the bedroom windowsill, and watch: standing in broad daylight, Annette offers Jean Luze the freshness of her twenty-two years. Their backs to Félicia, they claim each other without the slightest gesture. Desire bursting in their eyes. Jean Luze struggles, but there is no way out.

I am thirty-nine years old and still a virgin. The unenviable fate of most women in small Haitian towns. Is it like that everywhere? Are there towns in the world like this one, half mired in ancestral habits, people spying on each other? My town! My land! as they proudly call this dreary graveyard, where you see few men besides the doctor, the pharmacist, the priest, the district commandant, the mayor, the prefect, all of them newly appointed to their posts, all of them such typical “coast people” that it’s nauseating. Suitors are exotic birds, since parents here always dream of sending their sons away to Port-au-Prince or abroad to make learned men of them. One of them came back to us in the person of Dr. Audier, who studied in Paris and in whom I still search in vain for something superhuman . . .

I was born in 1900, a time when prejudice was at its height in this little region. Three groups emerged, isolated from each other like enemies: the “aristocrats” to whom we belonged, the petty bourgeois, and the common people. Tugged at by the delicate ambiguity of my situation, I suffered from an early age because of the dark color of my skin. The mahogany color I had inherited from some great-great-grandmother went off like a small bomb in the tight circle of whites and white-mulattoes with whom my parents socialized. But that is the past, and I don’t care to return to what is no more, at least not for now . . .

Father Paul says I have poisoned my mind with education. The truth is that my wits were asleep and I have stirred them—with this journal. I have discovered in myself unsuspected talents. I believe I can write. I believe I can think. I have become arrogant. I have become self-conscious. To reduce my inner life to what the eye can see, that’s my goal. A noble task! Will I succeed? To speak of myself is easy. All I have to do is lie a lot while convincing myself that I’m really putting my finger on it. I will attempt sincerity: solitude has made me bitter; I am like a fruit fallen before ripening, rotting under the tree unnoticed. Hurrah for Annette! After Justin Rollier, the poet who died of tuberculosis, there was Bob the Syrian; after Bob now Jean, brother-in-law to us both—and she is not yet twenty-three. Our little town of X is emancipating itself. It would seem we have been contaminated by what they call civilization.

I am the oldest of the three Clamont sisters. There are about eight years in age between each of us. We live together in this house, an undivided inheritance from our late parents. As usual, I have been entrusted with the more vexing tasks. You have nothing to do, so keep busy, they seem to say. And they have handed the keys to both house and strongbox over to me. I am at once servant and mistress of the house, a kind of housekeeper on whose shoulders rests the daily round of their lives. As recompense, each gives me something to live on. Annette works. A nice bourgeois girl ruined, cornered by circumstances, floundering shamelessly in compromise and promiscuity, and where else but as a salesgirl with Bob Charivi, a Syrian of the worst sort with a store on Grand-rue. Jean Luze, Félicia’s husband, a handsome Frenchman, beached on our welcoming shores by who knows what miracle, is in the employ of Mr. Long, an American executive who has been here for ten years. I need very little, and thanks to them I am gathering a fortune. I have developed a sordid miserliness in my old age. You should see me patiently counting my nest egg each month. “It’s dreadful,” Annette likes to say, “how Claire neglects herself!”

Félicia shrugs.

Since she got married, only Jean Luze exists. Gorgeous Jean Luze! Brilliant Jean Luze! The exotic and mysterious foreigner, who has set up his library and record collection in our house, and makes fun of our backward way of living and thinking. A flawless man, an ideal husband. Félicia’s cup overfloweth with love and admiration. I won’t be the one to open her eyes. From my window, I spy on their every move. This is how I came to find Annette in the arms of her Syrian boss one night. She was in the back of the car they had parked halfway in the garage. I saw everything, heard everything, despite all the precautions they were taking in order not to wake Félicia. They hadn’t thought of me. How could the old maid, uninterested in anything having to do with love, suspect them for one moment? That affair lasted until Félicia’s engagement. After that, everything fell apart for Annette again . . .

Félicia is of average height and on the voluptuous side, light-skinned with bland blond hair and the delicate features of a white woman. Although Annette is white too, there is gold under her skin. And her hair is black, blue-black like her eyes. Except for the skin color, she is a touched-up copy of me sixteen years ago. These two white-mulatto girls are my sisters. I am the surprise that mixed blood had in store for my parents, no doubt an unpleasant surprise in their day, given how they made me suffer . . . Times have changed, and I have learned with age to appreciate what has been given me. History is on the move and so is fashion, fortunately . . .

Jean Luze stares at Annette. He is struggling. And yet he knows very well that he will give in. When she has a man on the brain—and I have paid dearly for this bit of knowledge—she doesn’t give him up easily. And this one is among the most glamorous I have ever seen. The broad strides he takes in the yard! The way he climbs the stairs! His voice so young, so cheerful, and yet somewhat subdued and unaware of the cheer it spreads. His perfect speech! The way his gaze caresses everything so casually. Even me.

“Claire, how are you doing?”

He passes me by and goes up to his room, their room. But he doesn’t desire Félicia anymore, that much I know. Annette is the one on his mind. Besides, Félicia is ill served by her pregnancy. She is in no shape to defend herself. Her smile is more and more trusting, more and more mawkish, as Annette’s glances become more aggressive, more tormenting. How will this end? I keep vigil. I stand in the wings, I don’t exist for them. I push them onstage skillfully, without ever seeming to intervene, and yet I am directing. If only by the way I encourage Félicia to rest on the chaise longue on the balcony, all the while knowing that Annette and Jean Luze will be alone together downstairs in the dining room . . .

I close the doors, seemingly indifferent, and I wait. They stand there silent, devouring each other with their eyes, senses melting as they move in for the kill. This is not the right time yet. Annette cannot forget that Jean Luze is her brother-in-law, nor he that she is his wife’s sister.

For a while now we’ve been hanging our heads like snarling dogs, harassed as we are by fear, by the summer, the sun, by hunger and all that comes of it. The hurricanes are responsible, unleashed by God to punish us for what Father Paul calls our lack of faith and our weaknesses.

We stick out our tongues in this terrible sun in the throes of a Hai-tian summer. A thick, enormous, slavering tongue, licking at our skin, cutting off our breath. We are being cooked alive. Our sweat flows without pause. There is no moisture in the air, and the coffee, the only source of wealth around here, is drying up. Any day now, Eugénie Duclan, a friend of Father Paul the parish priest, will organize processions to persuade the clouds.

“Rain is a blessing from heaven,” Father Paul asserts in a very Hai-tian way during the course of his sermons.

So then we are cursed! Hurricanes, earthquakes and drought, nothing spares us. The beggars outnumber us. The survivors of the last hurricane, crippled and half-naked, haunt our gates. Everyone pretends not to see them. Hasn’t the poverty of others always been with us? After growing for the last ten years, it has the frozen face of habit. There have always been those who eat and those who fall asleep with an empty stomach. My father, a planter as well as a speculator, with over six hundred acres of land planted with coffee, accused the hungry of laziness.

“What is it that you do for a living?” he would say to those imploring him for a handout. And then he would answer his own question: “You beg.”

“Heartless!” Tonton Mathurin1 would cry out, “heartless!” Ah, the brave Tonton Mathurin we had learned to fear as if he were the very devil! He’s been dead twenty years now, and all these twenty years I always think I see him standing there when I pass his front door, draped in his old houpland2 and spitting at my father . . .

Misery, social injustice, all the injustices in the world, and they are countless, will disappear only with the human species. One remedies hundreds of miseries only to discover millions of others . . . It’s a lost cause. And of course there is the hunger of the body and that of the soul. And the hunger of the mind and the hunger of the senses. All sufferings are equal. To defend himself, man refines the meanness of his heart. By what miracle has this poor nation managed to stay so good, so welcoming, so joyful for so long, despite its poverty, despite injustice, prejudice, and our many civil wars? We have been practicing at cutting each other’s throats since Independence. The claws of our people have been growing and getting sharper. Hatred has hatched among us, and torturers have crawled out of the nest. They torture you before cutting your throat. It’s a colonial legacy to which we cling, just as we cling to French. We excel at the former but struggle with the latter. I often hear the prisoners’ screams. The prison is not far from my house. I see it from my window. The gray of its walls saddens the landscape. The police force has become vigilant. It monitors our every move. Its representative is Commandant Calédu, a ferocious black man who has been terrorizing us for about eight years now. He wields the right of life and death over us, and he abuses it.

Two days after his arrival, he searched almost every house in town. Anything that could pass for a weapon was confiscated, including Dr. Audier’s hunting rifle. Accompanied by policemen to secure the premises, he rifled through our closets and drawers, lips stiff with hatred. How many people has he murdered? How many have disappeared without a trace? How many have died under unspeakable conditions? And cruelty is contagious: kneeling on coarse salt, forcing a victim to count the blows tearing at his skin, his mouth stuffed with hot potatoes, these are a few of the minor punishments some of us inflict upon our child-servants. Upon those turned slaves by hunger, who must suffer our spite and rage in all its voluptuousness. My blood boils at the sound of their cries and those of the prisoners—rebellion grumbles in me. This goes back to the days when I hated my father for whipping the sons of our farmers for next to nothing.

Despite the ruins, despite the poverty, our little town remains beautiful. I realize this once in a while, in jolts of awareness. Habit destroys pleasure. I often walk past the sea and the mountains that frame the horizon in complete indifference. And yet, devastated as they are by erosion, the mountains are heartbreakingly beautiful. From a distance, the dried-up branches of the coffee bushes take on soothing pastel tones, and the shore is embroidered with foam. A smell of kelp seems to rise from the depths of the water. Small boats are tied to stakes on the shore. Their white sails stain the sea as the sky dives in and blends into the water. Once a week, we hear the American ship blow its horn. The only one moored in our port now, it leaves loaded with fish, coffee and precious wood. Our colonial-style house, part of its roof carried away by the wind in the last storm, is sixty years old. Each side leans on another house, Dora Soubiran’s on one side and Jane Bavière’s on the other—two childhood friends with whom we no longer associate for separate but equally valid reasons. Other houses, twins to ours, line the Grand-rue on both sides and are at odds with the modern villa of the new prefect, M. Trudor, a figure of authority whom everyone greets with a bow. We have lost our smugness and will greet anyone with a bow. Many a spine has been bent by all this scraping. M. Trudor hosts receptions to which all the former mulatto-bourgeois-aristocrats are invited. And the latter, taking thick skins out of their closets along with their silk dresses, respond promptly even as they grouse. One has to howl with the wolves, after all. And since the times have changed everything, we are making an effort to adapt. A few of us get our ears boxed, but Annette, bon vivant of the day that she is, takes care to represent us without overlooking a single invitation.

The rocky main street, just about demolished since the hurricanes, has been hollowed out by greenish ditches where mosquitoes nest. The mayor, a plump griffe3 with a taste for women and liquor, has other fish to fry. The decaying street is not among his preoccupations. He whiles away his time at the corner grocer’s, Mme Potiron, a grimelle4 who sells clairin5 infused with herbal aphrodisiacs. Beggars shivering with fever squat beside the ditches and cup their hands in the stinking water to drink it. In the narrow streets, some dilapidated shacks, holding on as well as they can atop their nearly ruined foundations, shelter suspect-looking families with hollow cheeks. A few poets hunted by the cops—who don’t trust what they call “the intellectuals”—also live there. The police are worried for nothing, since we have become as gentle as lambs and more cautious than turtles. Our endless civil wars have ages ago become the stuff of epic legend, regarded with a smile by our youth.

In the midst of this squalor, the prefect lives in style in his villa. He does not earn much, but he is rich.

“The good Lord has punished you,” he sighs when beggars hold out their hands.

“The good Lord is unhappy with you,” Father Paul echoes from his pulpit. “You are giving in to superstition. You practice voodoo. God has punished you.”

In the thirty years he has lived in this country and fought this religion, he hasn’t yet understood that nothing will ever uproot it. In order not to believe in it, in order not to seek the protection of the gods, one has to free oneself once and for all of everything, one has to shake the yoke of any divinity and count only on one’s own strength. Which I have done. But how can you stop this ignorant people from clinging to something they see as a life raft, when even its representatives, when even my own father, the Parisian mulatto, served his loas6 regularly.

Copyright © 2009 by Marie Vieux-Chauvet. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.