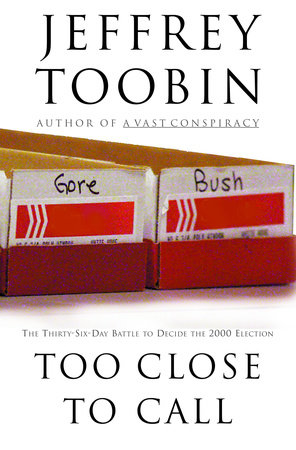

Prologue

Florida SunriseThe sun rising over the Atlantic casts a peach glow on the Lake Ida Shopping Plaza. Its architectural motif is typical of the lesser strip malls in Florida’s Palm Beach County-ersatz stucco, with a roof of battered tiles. The first rays of dawn land on Good Stuff Furniture, where factory-closeout sofas and love seats are sold on layaway. One storefront over, engineers and hard hats arrive early at the construction office for the job of widening I-95, the truck-choked superhighway whose low rumble and smoggy haze never entirely leave this commercial square. The medical office of Dr. Jean-Claude Tabuteau is open only at night, to serve his working-class Haitian clientele, men and women who spend their days changing sheets and watering lawns at the resorts on the other side of the highway.

On the morning of November 7, 2000-Election Day-the mall had none of its usual subtropical torpor. One of the storefronts was home to the Democratic Party of Palm Beach County, and its offices served as the base for the biggest get-out-the-vote operation that anyone could remember. The plan called for one group of volunteers to work the phones in the party offices and another to disperse to the precincts. The poll workers were to be given their assignments, as well as their leaflets and signs, at a long folding table just outside the front door. A woman named Liz Hyman was in charge of the table.

Hyman had spent a few years as a junior lawyer in the Clinton administration and was now a young associate at a prominent law firm in Washington. She had taken a few days off to help the Democrats try to retain the White House. The plan in Palm Beach County called for the volunteers to vote in their own precincts as soon as the polls opened at seven and then to report to party headquarters for instruction and deployment. It was only a few minutes after the hour when the first of them pulled into the parking lot.

Several-many-were distraught. There was something confusing about the ballot, they said. They weren’t sure if they had actually voted for Al Gore and Joe Lieberman. In keeping with the demographics of Delray Beach, the town where the mall was located, virtually all of the volunteers were elderly and many were Jewish. They had been especially motivated to support Lieberman, who was the first Jew to be nominated by a major party for vice president. What made the problem especially upsetting was that some of the volunteers thought they had voted for Pat Buchanan, a man they regarded as an anti-Semite. What, they wondered, could they do?

Liz Hyman had no idea. Indeed, she didn’t really understand what these people were talking about, and neither did anyone else at campaign headquarters. The local staff of the party had all voted by absentee ballot, so they had not seen the same voting machines as the volunteers who were arriving this morning. Like most politically attuned people, Hyman had a vague sense that voters were sometimes confused at the polls, but this seemed . . . different. These were experienced voters, indeed political veterans. Shouldn’t they have understood what they were doing? It was puzzling.

So Liz Hyman called her dad.

Lester Hyman had been a successful, if not famous, Washington lawyer for several decades. He had a bustling commercial practice, but he also offered discreet volunteer assistance to Democrats in the White House. He helped vet potential nominees for high-profile positions, reviewing their disclosure statements and personal histories for possible areas of embarrassment. Hyman had helped screen candidates for Bill Clinton’s first appointment to the Supreme Court of the United States-the seat that ultimately went to Ruth Bader Ginsburg. During that assignment, Hyman had met a young lawyer on the White House staff who was shepherding the nominee through the process. Now, when Hyman heard the peculiar report from his daughter in Palm Beach County, he remembered that the White

House lawyer had gone on to work for Al Gore. “I’ll give him a call,” Lester Hyman said.

Ron Klain’s cell phone rang just as he was pulling into the parking lot of Gore headquarters in Nashville. It was 8 a.m.

Eleven hours later (twelve in parts of the Panhandle), the polls closed in Florida and the presidential election came to its scheduled conclusion in that state. As it turned out, however, the race for president was so exquisitely close in Florida that no winner could be determined with assurance on election night. Because the electoral-vote margin between the candidates was so narrow across the nation, it quickly became apparent that the victor in

the Sunshine State would win the presidency. The battle raged in and over Florida for thirty-six more days, until Vice President Gore conceded the race to his Republican opponent, Governor George W. Bush, of Texas.

It is impossible to discuss the presidential election of 2000 without superlatives. The race between Bush and Gore was the closest presidential election in the modern history of the Electoral College. It prompted the greatest and fastest mobilization of legal and political talent that the nation had ever seen. It featured the most dramatic and numerous swings of fortune-not only during the post-Election Day period, but often over the course of single days. It included the most unlikely cast of characters for a major national drama-from once-obscure judges who held the fates of the candidates in their hands to the governor of Florida, who happened to be the younger brother of the Republican candidate for president. Even considering the infamous 1876 contest between Rutherford B. Hayes and Samuel J. Tilden, the race of 2000 was the most extended period of true uncertainty about the winner of a presidential election. And, of course, the battle between Bush and Gore was fought for the highest political stakes.

\The election of 2000 also produced the most sprawling and complex political and legal drama. In Florida, the cynosure was the state capital of Tallahassee, where the chief strategists for both sides plotted their appeals to the governor and secretary of state as well as to trial judges and the state supreme court. At the same time that the candidates were making their cases in the capital, there were equally tortuous and significant skirmishes being fought at the county level. Three of them were so dramatic that the counties themselves seemed almost to take on human qualities-the bumbling and childish Palm Beach, the efficient and mature Broward, the mysterious and sinister Miami-Dade. And yet this contest stretched far beyond the borders of Florida, consuming the entire country and concluding behind the closed doors of the United States Supreme Court.

The election of 2000 also produced the greatest controversy about the “true” result and the “real” winner-in Florida and thus in the election as a whole. This dispute gave rise to still another superlative. The ballots in Florida received more extensive scrutiny from outside-non-governmental-organizations than in any other American election. Alas, even those elaborate inquiries did not produce definite answers; indeed, the recounts conducted by the news media only deepened the confusion about who “really won.” Moreover, the news-media recounts, while understandable and worthwhile enterprises, at some level misconceived and misportrayed the way this election was really decided. Those recounts were based on the notion that the goal of the thirty-six-day battle was to identify an objective truth locked within the state’s ballot boxes. Under this approach, the election was over on November 7, and the candidates’ subsequent efforts were devoted to counting the votes that had already been cast.

A more useful way of thinking about this election, and understanding the final result, is to recognize that the campaign simply continued for more than a month after Election Day. The thirty-six-day battle was fought using many familiar tools, including speech making, image management, crowd building, and lobbying. The Bush campaign not only recognized this reality; its leaders did a great deal to create it. The Democrats treated the recount in a different way-as a discrete event, separate from the race for the White House. It was this fundamental difference in orientation that contributed most to George W. Bush’s victory. The Republicans were more organized and motivated, and also more ruthless, in their determination to win. From the very beginning, the Democratic effort was characterized by a hesitancy, almost a diffidence, that marked a clear contrast to the approach of their adversaries. In a situation like this, where the result was long in doubt, the distinctive attitudes made an important difference.

The reasons for these contrasts start with the candidates themselves. Al Gore had lived in Washington for most of his life, and he had absorbed, as if by osmosis, many of the attitudes of the establishment. He agonized about the views of the columnists, newspaper editorialists, and other elite opinion makers among whom he had lived for so long. Gore cared as much about their approval as he did about winning, and he ran his recount effort accordingly. Ironically, and poignantly, Gore’s solicitude toward the Washington establishment was never reciprocated. To a great extent, the vice president lacked passionate supporters among journalists and politicians, and even ordinary citizens. In the intense conditions of the Florida recount, this absence was notable. The recount required sacrifice, devotion, even a measure of fanaticism from those on the ground. At best, Gore inspired only a distant admiration from his supporters, and he paid the price in Florida.

In almost every respect, Bush was Gore’s opposite. The Texas governor was blithely disengaged from the details of the recount and, instead, trusted his subordinates, chief among them James A. Baker III, to deliver the correct result. Elite opinion mattered little to him; Bush was steeled by a sense of entitlement that protected him from criticism. He was shielded, too, by the devotion of those around him. His campaign and legal staff included a great number of people who were willing to do almost anything to see George W. Bush elected president of the United States. His supporters were willing to take risks, bet their careers, and bear almost any burden for a Republican victory. One candidate had supporters in the streets of Florida, and it wasn’t Al Gore.

This passion gap was the product of forces broader than the different personalities of the candidates. It had been eight years since Republicans controlled the White House, and their hunger for restoration was stronger than the Democrats’ desire to hang on. The presidency of Bill Clinton also gave Bush supporters an extra measure of intensity in this fight. The Republican Party had not just disagreed with Clinton’s policies during his administration; it had regarded him with an almost feral loathing. From the day Clinton was elected, Republicans described him as morally unfit and politically illegitimate, though they met a singular lack of success in persuading the greater American public that they were right. Republicans vented much of their anger against Clinton in legal settings-in lawsuits, investigations, and, ultimately, an impeachment. For Republicans, the Florida struggle against Gore, much of which also took place in courtrooms, served as a useful proxy for the failed onslaughts against Clinton.

Still, inasmuch as the post-election battle reflected the character of the candidates, the nature of their parties, and the state of contemporary politics, there was something else, too: random chance. The vote in Florida was bizarrely, freakishly close, and all the other states fell into place in such a way that the presidency turned on the result in that state alone. Florida itself is an anomalous, singular state, and the place where the electoral crisis of 2000 began-Palm Beach County-is a strange locale even by the standards of the Sunshine State. Error piled upon error, oddity upon oddity, surprise upon surprise. The trigger-the first trigger, anyway-was pulled in a strip mall.

Copyright © 2001 by Jeffrey Toobin. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.