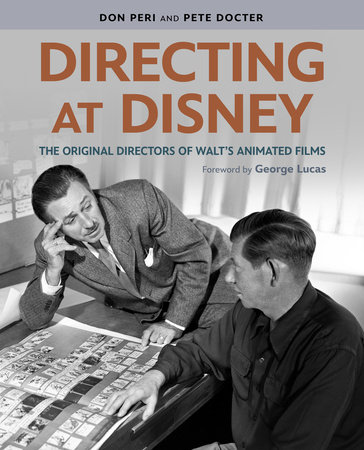

INTRODUCTION PETE: Some years ago, I was watching Peter Pan with my kids. As Peter, Wendy, Michael, and John leapt off Big Ben and flew over the clouds of London, I thought, Wow, what a great shot! I wonder who came up with that. Was it the director? Come to think of it, who was the director? As a huge fan of Disney films and history, I was embarrassed to admit I didn’t know.

At the time, I was directing Up at Pixar Animation Studios. As with all my directorial efforts, I had come up with the core idea and worked with a small group to craft the story and characters. I worked with writers, guided designers, directed actors, and steered and approved every shot in the film through camera, editorial, animation, effects, lighting, and final sound. Was this true of directors who had worked with Walt Disney?

My embarrassingly large shelf of Disney books revealed precious few facts—and even scant mention—of directors or their job. Why was this key position so unsung? I knew one person who might know more: my friend and Disney historian Don Peri.

DON: I have always been a “who” person, meaning that my interest in Disney has always centered on Walt Disney and the people who worked with and for him. Sure, I have loved the movies, the theme parks, some of the television shows, but I am not an artistic person, so the “how” of making films has been less a focus for me than who made them and their working relationships.

My odyssey through Disney history really took flight fifty years ago when the cover art for a college magazine led to a meeting with Ben Sharpsteen, a retired Disney animator, director, and producer. Ben and I both lived in Northern California, so we easily developed a working relationship: I helped him record his memoirs and he helped me expand my knowledge of Disney history in general and particularly his history and the history of those in his orbit. We worked together for three years, and then I ventured out to conduct many more interviews and to teach courses on Disney history, all the while honing my skills and knowledge. One of my interviews, with director Wilfred Jackson, led to a meeting with director Pete Docter. We shared a love of Disney history, and Pete not only knew the “how” of animation, but also yearned to know more about the “who.” This was the beginning of a beautiful friendship.

PETE: As Don and I researched and interviewed, we found Disney directors to be a bundle of contradictions. All artists they worked with saw directors as a central and powerful figure in the making of Disney films. But many directors were hated. Several were seen as having “failed up” into their position.

Even the job description was confusing. Some spoke of the role as glorified assistant to Walt, the real director; others spoke of directors being completely in charge, coming up with the concepts and dictating creative choices. We eventually found both to be true; the role changed over time and from project to project.

Ultimately we discovered the directors to be a fascinating insight into Walt himself. As he expanded from personally drawing a handful of short films and advertisements in the early twenties to overseeing shorts, features, television shows, and theme parks in the fifties, Walt developed people and processes that still allowed him to achieve his vision. In many ways, the evolution of the role of the director reflected Disney’s own growth as a creative leader.

DON: Walt Disney has always fascinated us, inspiring childhood wonder at the stories and worlds he introduced and then the more mature appreciation of the challenges he faced and the innovations in storytelling, animation, filmmaking, and technology he created with his dedicated team. It all came full circle when we watched Disney films or enjoyed his theme parks with our young families and relived his world through their lives.

The dilemma we faced with this book is that while we have the greatest respect and admiration for Walt, he was a taskmaster, and he would be the first to admit it. So in telling the stories of his band of animation directors, we see how his drive and ambition both inspired them and stressed them.

PETE: One quote that stuck with me was from a February 10, 1941, speech that Walt gave to his animation staff: “Those men who have worked closely with me in trying to organize and keep the studio rolling, and keep its chin above the water, should not be envied. Frankly, those fellows catch plenty of hell, and a lot of you can feel lucky that you don’t have too much contact with me.”

DON: But I think they would all say—were they still alive—that they would gladly do it again, because they believed strongly in his vision, were in awe of him personally, and readily attached themselves to his star for as long as they could hang on. His hold on their hearts and minds stayed long after his passing. I can remember interviewing many of them at the studio years later, and as we talked, they gradually shifted from the past tense to the present tense when speaking of him, and Walt was still alive for them. Swept up in their memories, I almost expected to hear his cough and see him come around the corner to join us.

Walt was a different person to each of his directors, depending on his needs at the time and their skills at delivering what he needed. Over the years, as his world expanded beyond animated films, his attention divided, and he expected his directors to take up the slack.

He often had an uneasy relationship with the role of director, which he virtually created within animation, and the men who filled that role. He was constantly changing the organization and studio process to fit his vision, and woe to the director who could not go with the flow.

For this book, we have simplified the evolution of the director into six periods or stages. These designations were certainly not anything discussed during their time, but they seemed the best way to explain the changes in this complex and sometimes technical role. Each section begins with a simple explanation of the job at that time and place.

But most of this book is devoted to the careers of the often unknown, unsung directors. Rising from the animation ranks, these men were a wide and varied group of characters. Capable of incredibly demanding precision, some delegated willingly, while others demanded meticulous control. They were boisterous, quiet, exacting, and creative. Some smoked and drank heavily. Some were hated, others revered. They all worked long hours. It was a highly stressful position, likely contributing to declining health for some in their later years.

As generals of the small armies it took to make these animated films, directors had an unequalled view of the art, craft, and organization it took to make them. And as Walt’s closest creative partners, they saw a side of Walt seen by very few.

We’re excited to introduce you to the talented but unknown people who directed some of the world’s favorite films.

—Don Peri and Pete Docter

February 2023

P.S. Within these pages, you will not see a lot of diversity. While today this is slowly changing, the films and the processes discussed in this book are products of their time. With hope of a more diverse group of directors in the future, we feel these stories have plenty of lessons to offer all filmmakers and historians today. —D.P. & P.D. PART 1 “THERE WERE NO DIRECTORS AT FIRST” 1920–1931 Throughout time, the job of the director changed. In an attempt to show this, we have created a series of simplified flowcharts, based largely on graphs prepared in the late 1970s by Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston for use in their book

The Illusion of Life. Ultimately unused, they still provided a firsthand account of the evolving system. Please note these charts are simplified, especially as time goes on, and are focused on the director’s duties and jurisdiction rather than on details of the production process.

1920s NEW YORK STUDIOS: No directors; animators do everything in making the film.

•

STUDIO OWNER: The boss owns the studio, makes distribution deals with theater owners, and runs the business, largely leaving the making of cartoons up to the animator.

•

ANIMATOR: Each short is divided among two to four animators. Each thinks up gags for their own section, stages them, makes the animation drawings, inks them, and inks a background on a cel to lay over the paper drawings of the character. With luck, the cameraman can draw, in case something doesn’t work or has been left out.

- GAGS

- LAYOUT

- ANIMATION

- INKING

- BACKGROUNDS

•

CAMERA •

FINAL FILM Output: one short a week 1920–1928 THE EARLY DAYS AT DISNEY’S: No directors; Walt determines what will end up on the screen, as well as the timing.

•

WALT: Walt oversees everything: the subject matter, the jokes, and the pacing of animation.

• GAGS & STORY • LAYOUT: Illustrators are hired to draw layouts, design the compositions, and paint backgrounds.

• ANIMATION: Animators are now free to focus 100 percent on entertainment and character performances.

• ANIMATION ASSISTANTS: Animation assistants do over half the drawings, allowing animators to handle twice as many scenes.

• INK & PAINT: Characters are traced onto clear sheets of plastic, called cels, by “inkers” and filled in with opaque paint by “painters.”

• BACKGROUND: Background is now a painting instead of a line drawing, requiring extra artists. (The animator is freed of this assignment.)

•

CAMERA •

FINAL FILM Output: one short every two weeks 1929–1931 THE PROTO-DIRECTOR: The role of the Director (called the “Story Man” at this point) is created to make sure the gags come off as discussed in prior meetings, and alleviate Walt’s time spent on details.

• WALT: Walt oversees everything: the subject matter, the jokes, and the pacing of animation.

• GAGS & STORY: Someone better at gags than animation gets a full-time job thinking up funny business.

• STORY MAN (aka Director): The Story Man oversees the largely organizational issues complicated by sound while Walt makes most creative decisions.

- ANIMATION

- INK & PAINT

- ASSISTANT

- ANIMATION

The Story Man’s job:

• Hand out shots to animators with spoken description of what is expected

• Review rough and cleaned-up animation

• Time out drawings, often removing or revising instructions to camera how many frames each should be seen on-screen

- LAYOUT

- ART DIRECTION

- BACKGROUNDS

Layout and background artists have the added responsibility of selecting colors.

- MUSIC

- SOUND EFFECTS

- CUTTER

The Director’s job includes the planning and recording of sound, usually done at the end of the picture. The inclusion of sound calls for a cutter (editor) to keep everything in sync.

•

CAMERA •

ANSWER PRINT: An answer print is now needed to check color corrections.

•

FINAL FILM Output: one short every four weeks CHAPTER 1 THE BIRTH OF THE DISNEY DIRECTOR “There were no directors at first. Disney produced directors—or rather, created them.”1 —Animator/Director Dick Huemer LIGHTS! CAMERA! ACTION! SOUND! When Al Jolson tells a cabaret crowd in

The Jazz Singer, “You ain’t heard nothin’ yet,” he meant more than he could possibly know. The movie studios were initially dismissive of this film from the upstart Warner Bros. Studio, but the public enthusiastically embraced it. And what the industry hoped was a fad in fact changed movies forever.

Sound meant big things for Walt Disney as well, establishing both him and Mickey Mouse as household names. It also ushered in a new position in the production of animated films: that of director.

BEFORE DIRECTORS When the very first animated films appeared around the turn of the twentieth century, there were no directors. The position would have been superfluous; with no actors, sets, costumes, or sound, what appeared on-screen was simply decided and drawn by the animator. Since early films were usually made by one or two artists, there was very little need for planning.

Even as small studios grew to churn out a more regular diet of cartoons, organization was loose. As then-animator Clyde “Gerry” Geronimi said of his work in New York around 1920, “There were no storyboards [visual scripts] in those days. We had just a typewritten sheet, with an outline of what we were going to do.” Animator Dick Huemer’s reference to his work at the Mintz Studio (Screen Gems) reflected a similar improvisational approach: “Sid [Marcus], Art [Davis], and myself each took a third of the picture, animated and amplified it on our own, with hardly any consultation with each other. We each considered our section our own private affair—gags, interpretation, and all.”

When he started in Kansas City, Walt Disney followed the same process. Along with fellow artist and friend Ub Iwerks, he animated on shorts and advertising products.

The failure of Walt’s first two studios precipitated a move to California, where he and brother Roy again hired Iwerks, recognizing his amazing ability to animate fast and with high quality. At the same time, Walt found that his strength was in story and character. “I am in no sense of the word a great artist, not even a great animator; I have always had men working for me whose skills were greater than my own. I am an idea man. “It wasn’t that Walt couldn’t do it [animate], he could,” recalled Ub years later. “But since I had joined him in 1924, he found he could do more for his pictures with gags and doing writing than by sitting over a drawing board. I don’t think Walt made any drawings after 1924.”

Walt wanted stories that were cohesive, unlike the loose themes pieced together at other studios. He began writing outlines, describing what would appear scene by scene. Soon the text was accompanied by a sketch previsualizing the layout, giving all animators working on the film a clear vision of how their parts fit into the whole.

Instead of just letting animators draw whatever they wanted, Walt and Ub now had a plan for their films, much like architectural blueprints for a building. While this planning took more time, it added immeasurably to the quality of the films, which seemed to be Walt’s single-minded goal.

Walt shepherded the stories from their inception through every revision and gag. He approved every camera angle. He dictated what happened in every shot, sometimes every frame, obsessing over every detail. While not credited as such onscreen, Walt was the first Disney director.

But it was sound that would really bring the position into focus.

Copyright © 2024 by Disney. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.