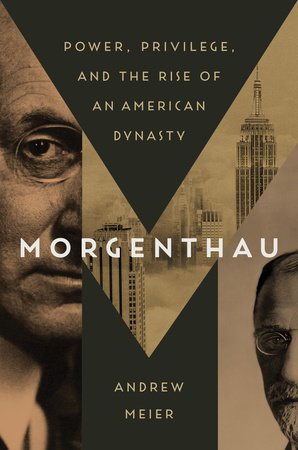

Between Profit and Disaster

1815–1866America in the first days of June 1866 was still rent by blood. On the morning that the iron ship edged into New York Harbor, the Civil War lived on. In Virginia, Jefferson Davis awaited trial for treason. Elsewhere in the South, the warnings mounted: In Alabama, the cotton forecasts turned apocalyptic and they spoke of famine; in Arkansas, the Freedmen’s Bureau reported ramifying destitution and a resurgent violence. Yet in the island-city that lay at the voyage’s end, the ebbing of the war had brought an uncertain limbo: Everyone, it seemed, both those who had witnessed the horror and those who had not, wished only to forget the fields of dead.

The SS Hermann, the 318-foot steamship, twin masts shimmering and black hull streaked salt-white, had left the port of Bremen in May. Not all of its 734 passengers would complete the crossing. Eleven children perished en route, the youngest an infant girl who died hours before landfall. For the 64 people in first class, though, the crossing had been most pleasant. A distinguished crowd had filled the heated suites of luxury. Most were German gentlemen, men of trade and industry, who had come to America in search of commerce and brought their families in hopes of starting anew.

On the final day at sea they rose early, huddling at the great glass windows to catch sight of a city cloaked in gray. Amid the predawn murk, an unlikely traveler who had sported a white silk tie on each day of the crossing, no matter the weather, stood apart. At fifty, he had already revealed a gift for self-invention—turning from tailor to tradesman to entrepreneur. Married for more than two decades, he had fathered thirteen children. He had left Mannheim with his family, but forfeited all else: a string of factories, a thousand employees, a mansion on the town square.

In short, he had left behind all that he had ever built, owned, or known.

Lazarus Morgenthau was not an imposing man. He was of average height and slight of build. Yet whenever he entered a room, no matter how crowded, people took note. It was a talent that he had discovered as a boy: He commanded attention. Although the bright blond hair and beard of his youth had turned a silvery gray, it remained rakishly long, and his eyes, set deep beneath a broad forehead, still flashed electric blue. He took pains to lavish care on his appearance. The daily toilette was an orchestration: a concerto of minerals and elixirs, lotions and oils. Each morning, he trimmed his walrus mustache with precision. He wore the stiff wool suits of a Baden aristocrat (his Prince Albert, a knee-length, double-breasted frock coat, was his signature) and, no matter the season, a cravat. The necktie, always silk and pearl white, served as a talisman of his preposterous ascent.

Lazarus Morgenthau was a child of the narrow world of Bavaria’s Jews, an unyielding realm of walls and boundaries, rules and ritual. It, too, was a world apart. In his father’s native Gleusdorf, a hamlet of some three hundred residents, only a few dozen were Jews. Their arrival dated to 1660: six families who settled in a remote corner of Europe. In the two centuries since, their number had scarcely grown. The Jews of Gleusdorf lived crammed together, along a dead-end street on the edge of the village. Lazarus, though, was a born gambler, and intent on escape. He came of age in a world where change was a threat and games of chance a sacrilege, and he had risen by dint of a rare combination of ego, defiance, and ingenuity.

Lazarus’s wife of twenty-three years, Babette, had made the voyage as well. Neither particularly pretty nor, as even the family chroniclers recorded, charming, Babette possessed a singular virtue noted by her descendants: an essential “stoic” bearing. At forty-one, she had not only suffered the mercurial ways of her husband, but borne children for nearly two decades. Eight were onboard: four boys, aged six to thirteen (Mengo, Julius, Heinrich, and Gustave), and four girls, aged eleven to twenty-one (Regine, Ida, Pauline, and Bertha).

Months earlier, Lazarus had dispatched the three he deemed most able, the two eldest sons, Max and Siegfried, aged eighteen and fourteen, and a daughter, Minna, fifteen. He sent them off in midwinter, a teenaged advance party instructed to secure a foothold across the sea. On November 29, 1865, Lazarus bid farewell to Max with characteristic flourish.

“My dear son!” he wrote in a poetic farewell,

You are parting from us today, just for a short timeMay you be the first to bring us hope and joy.Through diligence and righteousness you will succeedTo bring your parents and siblings a bright future.Travel now with God and my blessings and arriveIn health in New York—this is the wish of your loving father.Now, as the Hermann neared land, Lazarus and Babette waited among the arrivals, eager for a glimpse of the city. The clouds were dark and low, threatening to draw a curtain across the sky. Lazarus kept his leather cases close. They were filled with ornate scrolls, the promise of elaborate schemes: patents from Germany and England for hygienic devices and household remedies. Since his youth, Lazarus had been a tinkerer. In recent months, though, even before he had been forced, as he saw things, to quit the very business that had made him rich and abandon Germany, the drive to invent had overtaken his life.

Behind every scheme lay two forces: a love of modernity and a fixation on health. The first in Mannheim to install a bathroom in his house, Lazarus pursued one hygienic invention after another. Just months before leaving Bremen, he’d launched the latest venture: In London, Lazarus and his son Max opened a “branch office” at No. 10 Basinghall Street, securing an English patent for a favorite invention: Fichtennadel-Cigarren (“Pine-Balsam Cigars”), as well as Fichtennadel-Brustzucker (“Pine-Balsam Pectoral Sugar”)—bonbons, wrapped in foil and “containing a very little opium,” to alleviate “irritable cough, hoarseness, tightness of the chest, asthma, stubborn lung affections, chronic catarrh, etc.” To market the “wholesome cigars” among the Americans, he published a booklet filled with testimonials. Inside the embossed cover (crowded with the seals of fourteen European states), doctors and clergymen, opera singers and actresses, extolled Lazarus’s wonders. “These cigars are not only enjoyable to smoke,” a priest wrote, “they have truly earned their name, Gesundheits-Cigarren—Cigars for your Health.”

And yet a third force now ruled Lazarus: He was desperate to start over. Years later, his grandchildren would forgive what his own children could not. The patriarch could never have imagined, they understood, all that he did not live long enough to see. Lazarus would never revisit the world he had left, nor regain the fortune that he had lost. And he would never adapt to his new land. Yet the feats of his descendants would surpass even the gambler’s most fantastic dreams. His American-born heirs could forgive him. As Castle Garden came into view, its stone walls looming above the Battery, it would have been as hard to forecast the turns of the century to come as to envision the birth of a dynasty.

Copyright © 2022 by Andrew Meier. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.