Chapter One

Where these memories, dusted with gunpowder, begin

Cuba, 1979

With each shot I fired my body shuddered, the impact reverberating through every last joint, leaving an unbearable ringing in my head, sharp and disturbing. Shame kept me from admitting how much I hated firing a gun. I would squeeze my eyes shut as I pulled the trigger, praying that my arm wouldn’t tremble during that brief, blinding moment. After every shot I would feel a sudden, overwhelming urge to throw down the weapon as if it were on fire, as if my body could only be whole again once I let go of that lethal appendage gripped in my hand and pressed against my shoulder.

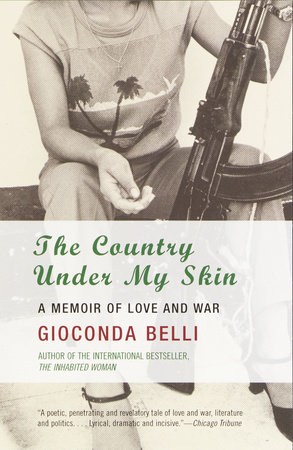

January 1979. Morning. A brisk northerly wind blew through a clear, cloudless sky. It would have been a perfect day for going to the beach, for lounging on the grass beneath a tree, gazing out at the Caribbean. Instead, I found myself at a shooting range with a group of Latin American guerrillas. In my arms, an AK-47. Behind me, observing us as he spoke with a group of people, was Fidel Castro.

Barely half an hour earlier, in an atmosphere reminiscent of a pleasant elementary school field trip, we had arrived at the modern and well-appointed shooting range of the FAR—the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias, the Cuban armed forces. Inside the munitions warehouse, where we were to select our weapons of choice, we were like children in a toy store, touching and studying the astonishing array of automatics, semiautomatics, machine guns, and pistols laid out before us. I had only shot with pistols before, and I wanted to know what it felt like to fire a rifle. After choosing our weapons, we went out to the field, and lined up to aim and fire at our targets, which were located directly across a ravine. For the first time in my life I felt the pounding in my shoulders, the power of the machine gun blasts, and the way the body loses balance if the feet are not planted firmly in the ground for support. The others began firing away enthusiastically, but I felt dazed and bewildered, floundering through a world of muffled sounds, as if underwater. These weapons gave me no thrill at all. In fact, they had precisely the opposite effect, for I emerged from the experience with a feeling of profound, visceral revulsion. Was I the only one who felt absolutely no fascination for these instruments of war? What would I do when it was my turn to enter combat? I continued firing, furious with myself. By the time I was finished, I was face down on a mound of earth clutching a .50 caliber machine gun, its long barrel rotating on its axis. I remained there, using my thumbs to pull the lever that activated the trigger. It was the most lethal weapon there. As I fired, I heard a dry, sharp boom and this time it didn’t pound through me and I was undeterred.

“I see you liked the .50, didn’t you?” Fidel mused with a malicious grin when I saw him a few days later. He had come to the hotel to visit the Sandinista delegation and we had’ been summoned to the presidential suite. I said nothing. I smiled at him. He turned back and continued talking to Tito and the other compañeros who had been invited to Havana for the Cuban Revolution’s twentieth-anniversary celebration.

I sat back and watched him. It was inevitable that the sight of Fidel would stir a collage of memories in my mind. Fidel was the first revolutionary I had ever heard of. When I was a child I had followed his rebellious feats as if they were episodes in an adventure novel. Sprawled out on our parents’ bed, my elder brother, Humberto, and I devoured the Life magazine issue with the story on Fidel in the Sierra Maestra. In our house, among the adults, passions always ran high when it came to Fidel.

Around this time, Humberto had perfected his a cappella imitation of Al Hirt’s trumpet. His greatest pride, however, was his masterful rendering of Daniel Santos’s singing. Santos, a Puerto Rican, had been catapulted into fame thanks to his nasal rendition of the anthem of the Cuban rebel movement. Humberto’s voice boomed through the house as he broke into song either in the shower or during other moments of sudden inspiration: “Adelante cubanos, que Cuba premiará vuestro heroismo, pues somos soldados que vamos a la Patria liberar” (“Onward, Cubans; Cuba will reward your heroism, for we are the soldiers who will free the Motherland”). It was listening to that song that I first experienced the call of patriotism. I would repeat it to myself, secretly thinking of Nicaragua’s tyrant, Somoza. To me, Fidel was a romantic hero. In Cuba, he and his bearded, fearless, daring young men were accomplishing things that nobody had been able to achieve in Nicaragua—neither my cousins, who were involved in the struggle, nor Pedro Joaquín Chamorro (the opposition leader), nor the Conservative Party. I was only ten years old when Fidel achieved his victory, but I remember how thrilled I felt. I applauded the Cuban Revolution as if it had been a victory for us as well.

Soon after, of course, all that enthusiasm vanished, as if spirited away by a magic spell. I don’t know exactly what happened, but between the nuns at school, my parents’ friends, the newspaper reports, and the conversations in my house, it began to appear that Fidel and his cronies had fooled the entire world, making themselves out to be good Christians when they were actually dangerous communists.

“Can you believe it?” my mother said. “Fidel appeared in Life with an enormous crucifix hanging from his neck, and now he calls himself an atheist. It’s an outrage!” The nuns told us horror stories about Cuba: about young children torn from their parents’ arms and sent to institutions where the state would reeducate them as communists who would know nothing of God. To be a communist was a terrible stigma—it was a capital sin, the surest path to hell. I remember feeling awful for all those poor Cuban children—that is, until I overheard something my maternal grandfather, Francisco Pereira, said to a Chinese friend of his who came to visit every day. Together they would sit back and enjoy afternoon drinks in their rocking chairs in front of my grandfather’s house in León. “It’s all lies. They’re inventing it all to sabotage Fidel,” my grandfather said. He would draw upon his encyclopedic memory and recite, word for word, excerpts of Castro’s speeches broadcast on Radio Havana that to me sounded like the homilies I’d heard in church offering solace to the poor. But with so many different perspectives before me, I didn’t know quite what to make of him. I was further confused when President Kennedy—my mother’s idol—turned to Luis Somoza Debayle, who ruled the country after his father’s death, to launch the Bay of Pigs invasion from Nicaragua. I couldn’t fathom how or why a president like Kennedy could maintain friendly relations with a government like ours.

Who would have ever guessed, then, that one day I would find myself seated on a fluffy sofa in Havana, talking to Fidel? But we come into the world with a ball of yarn to weave the fabric of our lives. One cannot know exactly what the tapestry will look like, but at a certain moment one can look back and say: Of course! It couldn’t have been any other way! That shiny thread, that stitching couldn’t have led anywhere else!

Copyright © 2002 by Gioconda Belli. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.