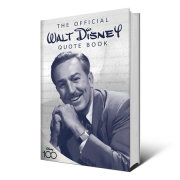

WED-Walter Elias Disney

The WED campus in Glendale, California, was hard to find. Hard to find because no one would expect the collection of nondescript old concrete tilt-up buildings to be where any self-respecting creative person would care to work. Getting there early, I scouted the neighborhood. It had to be the right address. But it was just a scattering of gray warehouses and some old aviation hangars. (Grand Central Airport had once occupied the site, explaining the lack of trees, lest Amelia Earhart scrape one on her takeoffs.) Down the street was the Batesville Casket Company, and the site was rounded out by that symbol of storytelling and cultural advancement, the Grand Central Bowl, designed by William Rudolph in the late 1950s and boasting sixty lanes. It also adopted the treeless parking lot scheme for consistency and included a coffee shop and the Gay 90s Room. I suspected the dark bar opened before10:00 a.m.

The 800 Sonora Avenue building had sounded interesting on the phone, a kind of Disney version of Los Angeles’s historic Mexican festival marketplace on Olvera Street. No such luck. It was as plain as a gray shoe box, with a strange batwing concrete rain canopy, looking like it was trying to fly out of its facade. Years later I would hear John Hench, first hired by Walt Disney to work on

Fantasia, and a true Disney legend, say, “They don’t come out of the show, humming the architecture.” They certainly didn’t in WED’s neighborhood.

In a few hours, I quickly went from a rejection letter to two possible jobs. Inside the concrete jungle, WED changed from an industrial wasteland to Santa’s Workshop without the snow. There was exciting work everywhere, models, paintings, robotic creatures, and human figures being built and animated. It was the largest assembly of creativity I could possibly have imagined. Here’s where I first heard the term coordinator. I didn’t know what a coordinator was, but they sure seemed to need a lot of them. I started to believe it might be the balloon salesman of the WED business, the job no one wanted but someone had to do. There seemed to be a lot of chiefs, seniors, and “nine old men” types (though there were more than nine, and they were certainly not all men). These seemed to be the legends entrusted with Walt’s last dream, and they knew Walt’s dream because they had worked for many years directly with him. Then there was a professional layer that seemed to be coming in, filling the space, like water filling around. The projects had become too large, too complex, and the old ways left too much to chance. And the stakes seemed to be higher than they’d ever been before.

It was at this time, I learned later, that Imagineer Orlando Ferrante had set the vision for the role of coordinator. He saw them as young, hardworking Imagineers who formed the glue—managing projects—knowing everyone, knowing the schedule, and knowing how best to expedite a complex sequence. He saw them coming from any field, and the job being a great jumping-off point to a successful career at WED.

I was offered a job on EPCOT. The future, the dream. I was going to be a part of this massive operation to build Walt’s experimental community, to impact the world and design. It would bring everything together—my theater design, my urban planning and architecture. And given the chance, I was planning on coordinating the hell out of it, whatever that meant.

Despite a long day of interviewing, my recruiter asked if I had time and energy for one more. She told me it was not as exciting as what I had seen so far. We walked outside the secure boundary of WED and down toward the Grand Central Bowl. Oh no, I thought. I prayed they weren’t recruiting for frycooks or pinsetters.

We crossed the street and entered another building. This one had none of the magic of the rest of WED. It looked a bit like a legal or accounting office,with its tan carpet, cubicles, and small offices with white walls.

But the recruiter took me into one room that had a floor-to-ceiling modelon the wall. It was obviously a Disney project, but it was surrounded on three sides by water. It was the bay side location of a top secret project called Tokyo Disneyland (TDL).

The TDL office, as it was called, didn’t have much to offer me. They made it clear there was very little design to be done; and just a small team. But lots to be figured out; Disney’s first attempt to build a project outside the comfort of the United States. On the walls of one big room was a smattering of colored index cards with work items and completion dates typed on them. Part of this new coordinating job would be to turn this wall into a vibrant center of status for the project. Maybe it was my lack of imagination, but I had trouble seeing these cards as the vibrant center of anything, no matter how many colors came in one pack.

But I ended up in the office of Frank Stanek. Frank was clearly the highest executive I had met that day. He was interesting, clear, and professional. And he read my mind immediately. “You just got out of design school, and you want to be creative. I know, I saw your portfolio. But I don’t need anyone creative, I need people to get this hard job done!” The only weird thing about Frank is he had a strange laugh, sort of like a seal gasping for oxygen. And I felt strongly that I had come here to design, and be creative, so his laugh wasn’t helping.

It was not until years later that Frank said it exactly like this, but I remember he implied it in our first meeting: “Bob, everyone is busy on EPCOT, so I’m goingto get this done with a very small team. It’s going to be done with the fired, the retired, and the recently hired!” And the laugh again. I could learn everything about Disney on TDL, he said. I could have a lot of responsibility, quickly, he said. “And if you get this done, you’ll have lots of new opportunities to design and be creative.”

Frank had a coup de grâce, and he hadn’t played it. I suspected he was waiting for the right moment. Some influences I’d not heard from my subconscious were welling up for the first time in a while: the world, urban planning, cities, international challenges. “And it will likely involve travel to Japan, an opportunity to live abroad, and travel to many places in Asia.

”Bingo! やった, or Yatta, as the Japanese might say! I started to imagine ways to turn that wall of pastel index cards into a stunning example of information architecture.

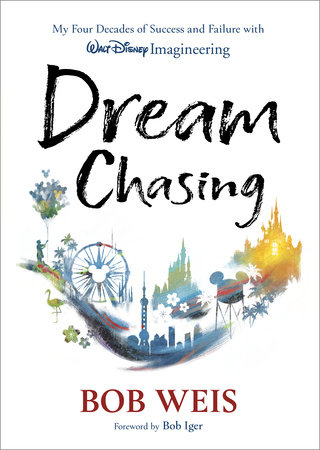

Copyright © 2024 by Bob Weis and Foreword by Bob Iger. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.