***This excerpt is from an advance uncorrected copy proof***

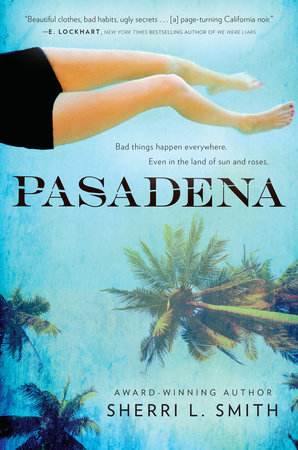

Copyright © 2016 Sherri L. Smith

Maggie always was a fucking train wreck. Leave it to her to end up facedown in a swimming pool on the hottest day of summer.

Caller ID shows Joey called five times. The sixth time, he left a message. I played it once, the phone close to my ear, then listened to the echo of my own breathing over the open line, waiting for his words to sink in. When they did, I hung up.

“I have to go home.”

“What?” Danielle says. We’re at a diner in Cape May on the Jersey Shore. My cousin shovels a handful of fried clam strips into her face. “We just got here,” she says, her mouth stuffed. It’s disgusting.

I turn and look out the window. Summer rain dots the plate glass, turning the trees along the side of the road into watercolor. Across the street, well-tended Victorian houses staunchly ignore the shower as tourists run by in flip-flops and canopied bicycle surreys.

It’s my first time back to see family since my mother and I moved out west. I thought I’d been missing the East Coast, but there’s a sour feeling in my stomach, one I haven’t felt since the last time I was here.

We’d gone to California to be new people, to have a fresh start. But bad things happen everywhere. Even in the land of sun and roses.

That’s why I left for the summer. And that’s why I’m going back again.

I shake my head, annoyed at Dani after the thunderclap of bad news. “Not your home. Mine.”

Dani’s dark lashes flutter and her eyes go wide. “Back to LA?”

My cousin loves the thought of it—Hollywood, Los Angeles. She resents me for being here when we could have both been back there for the summer. But I don’t live in LA, her fabled City of Angels. I live on the outskirts, in Pasadena.

I shut the phone in my hand, pressing it to my cheek like an ice pack that can stop the pounding in my head. “Maggie’s dead.”

Dani’s mouth forms a perfect O of stupidity. “Your BFF?” “That’s the one.”

Dani’s face turns a shade of gray. “Oh, Jude, that’s awful. What happened?”

I don’t answer because I don’t know.

Dani waits, clears her throat. Then she starts in on her French fries.

I unlock my phone and call the airline, avoiding the text messages in the open window, the ones that Maggie would never respond to now.

I turn back to the scene out the window, pressing but- tons in the voice mail tree to book my flight. The rain, the incessant greenery feels flamboyant next to my memory of California. Water streams down the window, tracing shadows on my skin like the promise of tears. Three hundred fifty dollars is the cost of changing my summer plans. The cover charge for the suicide of my best friend. I stifle a laugh, and feel a hole opening up inside me. Maggie’s gone.

But why?

There must be a reason.

That’s what I tell myself the entire ride to the airport.

Strung out on too much adult sympathy and not enough sleep, I try to drum logic into my head.

My aunt and cousin drop me at the terminal with its forced air and forced smiles. They don’t give gifts or linger. No cash in the palm, or saltwater taffy. I’ve tainted their perfect summer.

When I hand the airline rep my bereavement-rate ticket, he realizes I’m a minor traveling alone and I get special treatment. At seventeen, they don’t give me any cheap plastic wings. Just a seat against the bulkhead, where the flight attendants can keep an eye on me, and a Diet Coke before takeoff.

I tell myself that I haven’t had time to call Joey. Not between packing and travel. He would know what really happened. Joey’s good at that. Knowing. Except for when it comes to him and me. Besides, I don’t want to know just yet. Details are pedestrian when it comes to suicide— overdose, razor blade, gunshot, asphyxiation. There are only so many ways to off yourself. It’s not really the how that matters anyway, just the who, the what, and the why.

The who is Maggie. Drop-dead gorgeous Maggie Kim. The last time I saw her out by the pool, she was dressed like a movie star—black one-piece suit, strapless, the same thick ebony as her glossy bob of hair. Big round sunglasses that would have made me look like a bug, but looked elegant on her. She’d worn a sheer black robe over it all, and candy-apple-red patent leather mules that clacked loudly on the pebbled surface of the deck but matched the polish on her manicure and toes.

She’d held a cigarette between perfectly painted lips, one of those nasty little filterless things that she loved so much she’d order them online by the boxful. You’d have thought it was a brick of heroin, the way she clung to the box when the UPS delivery came.

I tried one once, when she wasn’t looking. Me, the Goody Two-shoes, the Sandra Dee. I didn’t even light it. The taste of tobacco on my lips was enough to make me puke.

She caught me hunched over the toilet and smiled with those professionally pearly whites, so striking against her red lips and almond-brown skin. “Don’t mess with Mommy’s candy,” she’d told me. Then she’d laughed and held my hair, even though it was already in a ponytail.

Poor Maggie. I failed her.

Between the complimentary drink service and the meal cart, I finally break down and cry.

Chapter 2

California rises up to meet me. The jet wheels hit the tarmac with a 2.5 Richter rumble.

Home. It’s so bright out here, so the opposite of my green summer getaway.

I dig into my bag for sunglasses and come up empty. In a flash, I can see them, three thousand miles away, lying on my borrowed bed. Figures. I squint and make my way to the cabstand.

When the 101 Freeway gives way to the 134, my pulse quickens. We speed through Glendale and Eagle Rock, the smudgy soup bowl of Downtown LA spread out to my right. The hillside on my left is blasted, the golden-brown grass singed to a blackened streak of a cigarette-caused wildfire that probably shut down traffic for most of rush hour. I lower my window and try to smell the smoke, but it’s long gone, eradicated by LA’s finest. I close the window. It’s almost good to be home.

Almost.

And then we’re at Orange Grove, peeling off the free- way to the south, and a lump the size of a lemon hits my throat. “Stop here,” I say as we reach Colorado Boulevard and the stretch of stores crowding the street with tourists and locals alike. I pay the man and find a store with a sunglass stand for the unprepared. Sunblock and hats fill the back of the rack. In February, it’ll be ponchos and umbrellas.

I buy two pairs of cheap glasses. Not fashionable, but at least they hide my red eyes.

Big girls don’t cry, Maggie used to say. They get even.

Joey answers his phone before the first ring ends. “Joe, I’m back. I’m at the Coffee Bean on Fair Oaks. Come get me?”

I didn’t even have to ask. I heard his car keys the minute he said hello. He’s got a special ringtone for me. Everyone used to tease me about it. A song from an old movie. Supposed to be romantic, but I’ve never seen it.

“Welcome back,” Joey says, bumping into an empty chair in his rush to greet me.

I’m in the back of the coffeehouse, away from the picture windows and the summer crowds, at a small wooden table for two. I take my feet off the extra chair, put down my iced coffee, and let him pull me into a hug. It’s awkward and lasts too long for my comfort, but I figure he needs it. He deserves it. Joey’s the one who found Maggie’s body.

He wraps his arms around my bare shoulders and clings to me, smelling of fabric softener and boy sweat.

“Jude, it was awful. I—”

That lump in my throat is getting bigger. “Not here, Joey. Not yet.” My eyes ache. It would be a mistake to cry in front of him. A cliché, one he’d be quick to embrace. I shake my head, my voice barely a whisper. “In the car, okay?”

“Sorry,” he says, pulling away. His fingers leave my skin reluctantly. I shrug and take in his gangly figure, shredded jeans, and the ever-present unbuttoned shirt over a plain white tee. This is Joey’s uniform. Only the state of the jeans and the color of the shirt changes. It’s reliable, like him.

“Thanks for coming to get me.”

“Sure, no problem.” Suddenly, he’s all elbows and shy glances, no longer looking at me directly. He’s gotten taller since school ended. Not a great development for a kid who already looked like a young giraffe.

“This your bag?” he asks, reaching for my pink-and- purple duffel. I don’t answer, just grab my matching back- pack and follow him out the door.

“Did you want a drink or something?” I ask belatedly. “My treat.”

“Not now, thanks. I just hit Jamba Juice before you called.” He pats his nonexistent stomach and swings my bag over his shoulder.

“Sorry I’m parked so far away,” he says as we head south, away from the shopping area. “The lot was full and parking is a bitch around here on a Sunday.”

“Yeah.” I suck the last of my drink dry and roll the sweating plastic cup against my cheek. It’s oven-hot today, and the city smells like a dozen little grass fires waiting to happen.

“Here we are,” Joey says, tweaking the unlock button on his car key. A silver ZX convertible bleats in response. The top is down to protect it from being sliced by stereo thieves. Radios are cheap. Soft tops are not. Joey tosses my bag in the back and we climb in.

I kick off my clogs and put my feet on the dashboard. Joey pulls an old paperback out of my way and drops it in the backseat.

Maggie used to do this—take her shoes off in the car. Even in winter. She drove barefoot too. Said she could feel the road better that way.

I feel five hours of airplane cramps and a knot in my stomach.

There are reasons I went away for the summer. But now I’m back. Still, there’s no need to head home. Not just yet.

“Can we go to Maggie’s?” I ask. “I should see her parents.”

“Sure,” Joey says. And like the good boy he is, he drives in silence, radio off, and lets me gather my thoughts.

We drive down along the arroyo, big houses looking confused at the passing of the century. Craftsman mansions and stone monoliths that look like scattered university buildings rather than private homes. Oaks and magnolias shade the curving boulevards with names like characters from Fitzgerald novels. I read them as they go by.

The magnolia trees are in bloom and the air is alive with the thick scent of flowers and pollen. Joey’s car is dusted in yellow granules that blow past us as we drive. I take a deep breath, drawing summer into my lungs. “Okay,” I say. “Tell me.”

Joey wipes his nose, clears his throat, and sniffs. He keeps one hand on the wheel and his eyes on the road. “I don’t know. I just. I hadn’t seen her in a couple of days, but we were supposed to catch a matinee. We had talked about it at Dane’s birthday party. I took the side gate, came around the corner of the house, and there she was. Floating. But not facedown like in the movies. She was looking up, with the sun on her face. I thought she was swimming, but she didn’t move, she didn’t answer when I said her name. I jumped in, pulled her out, tried to get her breathing, but it didn’t help. I screamed until her father came to the back door. He called 9-1-1.”

I listen to Joey recount the details of my best friend’s death, how she looked, how the pool was cold. How her lips were tinged with blue.

I revise the image in my mind: Maggie, faceup, staring at the sky. Estimated time of death: 11:00 p.m. He tells me the paramedics called the coroner’s office. How there was an autopsy, rushed because the coroner knew the family. Mr. Kim is a somebody in Pasadena.

It’s likely the Kims panicked out of concern for their son, Parker. He “isn’t well,” as the understatement goes. The slightest hint of danger to his health, and he gets whisked away to a roomful of doctors. If Maggie had died of anything contagious, they’d want to know. Their little boy has been dying slowly for so long, heaven forbid something like swine flu come along and kill him overnight.

But it wasn’t swine flu.

We reach Maggie’s street, a wide treeless avenue except for a few ridiculously tall palms, the kind that are deadly in high winds with their razor-blade sheaves flying like weighted boomerangs. No fruit, no flowers, and not a lick of shade. They’re wealthy trees, arrogant and useless. They remind me of Maggie’s parents.

“It was an accident,” I say as we make the turn. The block is silent except for the ticking heat-click of air con- ditioners and the hum of the car. Maggie had called me before, threatening to kill herself. That’s how I know she would never follow through. She loved the drama, and drama needs an audience. “It was an accident,” I say again.

Joey doesn’t look at me. “The coroner said suicide.” I take a deep breath. “Why? What did he find?”

He stays silent a moment. “They’re still running tests.” I lean forward, as if I can intimidate him into answering me. “Tests. On what?”

Joey shakes his head, as if he still can’t believe it. “A bellyful of drugs.”

“Violetta,” I say by way of greeting when the home health aide answers the door. Parker must be back home from wheelchair camp if Violetta’s here. Maggie’s inoperable- tumor-filled brother is smart as a whip. He bites like one too. I used to think he was cute, when I was young enough to mistake sarcasm for flirting. I outgrew it.

“Mrs. Kim is in the garden,” Violetta says. She holds the door open for me and Joey, then runs back upstairs. There’s an elevator in the kitchen, but I guess that’s for private use only. They treat Violetta like a butler, but she draws some of her own lines.

The house is hot. The Kims are rich enough to be stingy about things like climate control. Mr. Kim drives a ten-year-old imported sedan. The house is as formal on the inside as it is out front, if a little better preserved. Where the shutters are fading on the facade, the interior reads like a page from Architectural Digest circa 1992. Pale peach walls and pooled drapery abound.

Joey and I make our way through the sunken living room, not bothering to take off our shoes. French doors off a stiff, plastic-covered chintz family room lead to the upper terrace of the backyard. I pause with one hand on the door.

Mrs. Kim is kneeling in front of an explosion of Da- vid Austin roses like a nun at the altar. A giant hat that matches the floral living room drapes protects her pale perfect skin from the sun. For a moment, she looks like Maggie and I can almost pretend.

But then she rocks back on her heels and I see the expression on her face. Peaceful, in a way Maggie never was.

In a way that’s out of place for a woman whose only daughter died yesterday.

“Mrs. Kim?”

She jumps, a gardening glove flung to her throat.

“Oh, you startled me,” she says in her softly accented English. I think Mrs. Kim wanted to be an actress—she has the feel of a starlet playing at being a Korean-American housewife. Old-world gentility and Western wiles. At least I know where Maggie got the idea.

“Sorry to scare you,” I say.

Joey clears his throat, shifts nervously behind me. “Hi, Mrs. Kim.”

He seems to fade more than step back into the house. This is the boy who found their daughter’s body. If the police had considered foul play, Joey would be the prime suspect. As it is, he acts guilty. He’s the one who opened Schrödinger’s box. If he hadn’t come over, hadn’t found the body, as far as any of us would know, Maggie’d still be alive.

To us, anyway. At least until the pool guy came.

Joey makes his excuses and exits, shutting the French doors behind him. Mrs. Kim and I regard each other blankly until the latch clicks shut, like a starting pistol. She immediately assumes the stoic expression of a woman suffering another loss in a long, painful life. You would almost believe she had weathered a war, lost people a life- time ago. Maybe she had. She sighs and climbs to her feet.

I step toward her, close enough to see that the perfect skin is turning to crepe. Her lipstick bleeds just outside the edge of her sad smile, into the lines of age.

She pulls off her gloves and drops them to the slate patio. I reach out and take both her hands in my own. It’s as close to a hug as Mrs. Kim and I have ever managed.

“I’m glad you’re back,” she says, her voice suddenly thick with emotion.

“I don’t know what to say,” I admit. “I . . .” Words skitter away and I squeeze Mrs. Kim’s hands instead.

She seems to recall herself and pulls away, exclaiming like a schoolgirl from another century, “Oh, goodness! My hands are so dirty. Let me wash them. Come inside. Violetta made iced tea this morning. I’m sure Parker hasn’t finished it all.”

I follow her back in through the dim cave of the house, thick white carpets and double-high ceilings fighting for the right to swallow every sound.

Joey is nowhere in sight. Through the windowpane set into the front door, I can see his escape route. He’s waiting on the curb, leaning against his car. Crying.

“So, obviously, Maggie didn’t have a will, but I’m sure she’d be happy for you to have anything that you want of hers,” Mrs. Kim says, scrubbing her hands furiously at the kitchen sink.

I stand across from her at the large granite-topped is- land and lean in to smell a vase of red roses. Mrs. Kim only grows pinks and whites. Pulling back from the vase, I see the card from the florist, tucked into a small envelope. Sympathy flowers, then. Red. An odd choice. Unless they were from someone who knew Maggie well. Pink and white might suit Mrs. Kim, but her daughter’s tastes ran darker. Flowers were just the start.

“You know where the glasses are,” Mrs. Kim continues, pointing the way with her chin. I go to the cupboard and take down two tumblers, filling them from a half-empty pitcher of iced green tea off the door of the double-wide commercial-grade fridge.

“We’re thinking Thursday for the funeral. Enough time for my brother and parents to fly out from Korea,” Mrs. Kim says. “I’ll let you know . . . send an e-mail or some- thing, when the plans are finalized. If you wouldn’t mind telling her friends. I don’t know them all, but they are welcome to come.” She dries her hands on a waffle-weave towel and takes a long drink of the tea I pass to her.

“I needed that. It’s so hot today,” she says conversation- ally, taking off her hat. She fans her face with the brim before dropping it to the counter, her eyes fixed on some point over my shoulder. “Oh, Jude.” She says my name softly, like a curse word, like a prayer.

“I always knew Maggie would go to Hell,” she says. “It’s hard for a mother to know that about her own child.” Her eyes drift to mine. “You understand?”

A spike of anger goes through me. But I nod, to keep her talking, to keep from saying anything I can’t take back.

Mrs. Kim looks down at the water rings our glasses have left on the countertop. She picks up her hat, drops it, does it again. “It wasn’t too late for redemption. But she’s made sure of it now. You see, I knew about the

nights she’d sneak out, or have her friends over. The boys, the smoking, the running around. A mother knows. But suici . . .” She can’t say it and swallows the word. “My baby died, and I didn’t even feel her go.”

Finally, this eggshell of a woman cracks, sudden tears aging her face a thousand years. She grips the counter with both hands as if it’s a dial that can reverse death. But the counter remains unmoved. A moment later, her crying jag done, she wipes her face with a napkin I pull from the rooster-shaped holder on the counter and dashes the tears from her eyes.

“I’m tired,” she tells me. “I think I’ll lie down. Go on out to the pool house. Take whatever you’d like. Violetta can see you out.”

I nod and watch Mrs. Kim glide away into the foyer and up the curving stairs. She looks nothing like her daughter now. She looks defeated.

Even beaten and battered, Maggie never did. Then again, the only beatings Maggie took were by choice.

Once Mrs. Kim is gone, I text Joey to meet me out back. I’m ready now. I want him to tell me the rest of what he saw, how he found her. I don’t stop to think that it might bother him to return to the scene of her death.

It’s funny. I always thought I’d be the one to find

Maggie’s body. I was the one on speed dial for every cri- sis. But she didn’t call me that night. Who did she call instead? If not me and not Joey, then maybe no one. But something just doesn’t feel right.

“I’m going to do it,” she said. “It’s the only way.” “What?” I was in my room, under the covers, cell phone pressed to my ear. I could barely understand her through her sobs.

“I’m better off dead,” Maggie said. “I already know a way. And then I’ll be fine. Okay? I just wanted you to know. I love you.”

“Maggie, don’t be stupid,” I said, already out of bed, stealing my mother’s car keys, trying not to scream. If I screamed, I’d wake the house, wasting time. “I’m coming.” “Don’t.” Maggie had stopped crying. She sounded resigned.

I moved faster, starting the car, still in my pajamas. “Maggie, wait.”

“If only you knew,” she said, and hung up.

I dropped the phone and ran a stop sign to reach her in time. Raced through the side yard, clanging the gate loud enough to set the neighbor’s Pekingese yapping. I slipped, skidding alongside the swimming pool, and landed at the front step of the pool house, a one-room stucco cottage at the back of the yard that had been her room since she was fifteen.

I slammed into the front door, throwing it open. “Well, you took your time,” Maggie said.

No blood on the floor, no bottle of pills, no pile of tis- sues or tear streaks or broken glass. Just Maggie on the sofa—a graying hand-me-down from the eighties—her cordless phone in one hand. “She’s here, gotta go.”

She hung up with whoever and grinned at me. “Want a G and T? I smuggled a bottle from the big house yesterday.” She rose and rummaged through the mini fridge in the tiny kitchenette, emerging with a large bottle of Bombay Sapphire. Resting it on the coffee table with a heavy thunk, she dropped back onto the sofa, arranged her pink cat-print pajamas, and took a drag from one of those damned filterless cigarettes.

“Well?” she said, looking at me—shaking, queasy with fear and anger, collapsed against the front door.

“Well, what?” I managed to say. “I thought you’d be dead.”

“I am dying. Of boredom. I call it a surprise slumber party. You like? Starts with a bang.” She stubbed out her

cigarette and stretched like a cat. “Oh, don’t pout. Take off your coat and have a drink. We’ll watch a movie. That Touch of Mink just ended.” She pointed to the TV with her glass. Doris Day’s credit was rolling by. “But another one’s about to begin.”

The pool house is empty now. The little building seems to sag, the stucco faded, the windows dark. No stench of burning cigarettes, no glasses of gin and tonic. The bed is unmade and there’s a half-eaten bowl of popcorn on the counter. The thrift store décor is no longer ironic, just tattered and worn without the glamour girl for a foil.

I pace the room. She didn’t leave a note. Then again, most suicides don’t. I sit on the sofa, staring at the un- made bed on the opposite wall, the TV stand that swivels to face either one, depending on where she lay. The TV is facing me. I wonder if the dent in the mattress matches her hips.

Maggie, what did you do? Joey knocks outside. “Come in.”

“You all right?” he asks. I should be the one asking him. “Yeah,” I say. “Just thinking.”

“About what?”

“Pajama parties.” I brush my hair from my face. “Her mom said I could take anything I wanted.”

“Yeah,” Joey says. “She told me that too.” I look up at him. “What did you take?”

Joey blushes and I’m afraid he’s going to say underwear or something equally perverted. Instead he points to the low bookshelf at the foot of the bed, the one holding up the TV on its swivel stand.

“I lent her my copy of Cyrano de Bergerac in ninth grade. I just took it back.”

I nod, relieved. Maggie has a lot of things that are mine. Things that come with being the same dress size and in the same classes—borrowed clothes, forgotten books. But I don’t want them back. She should go into the afterlife with some possessions.

All I really want are answers.

I move over to the bed and lie down on it. Joey watches me self-consciously. The dent in the mattress is too big for my hips. I sit up suddenly. Maggie wasn’t alone here last night. I jump up from the bed, wondering if the cops bothered to check it for blood, hair, or other things. I go into the top drawer of her tiny dresser, pulling out her underwear and lingerie.

“Oh, Christ,” Joey says, his mind going to where mine had been a few minutes before.

“Shut up. I’m looking for her pink slip.” She’d bought it as a joke in the old-lady section of Macy’s where they still sold the girdles and undergarments our grandmothers wore. A pale pink slip with tea-colored lace around the edges. She said it made her feel glamorous, like an old- time Hollywood movie star. It was her favorite outfit for seducing new boys. It made her confident, and the thin fabric outlined her “assets.”

“It’s not here.” I check the hamper. Empty. “You said you found her in the pool?”

Joey clears his throat, sounding oddly strangled when he speaks. “Yes.”

“In a swimsuit?” I ask.

“Um, no. In a nightgown or something. I thought she was naked at first. It clung to her.”

I hang my head. “Pink. With tan lace.”

Joey nods. “And a tiny pink rose. Right here.” He presses his finger to the middle of his chest. “I kept staring at it when I did CPR, thinking if the rose rises, she’s breathing, she’s alive.”

“Huh,” I say. It comes out as a sob.

“What? Does that mean something?” he asks.

I nod, trying to force back my tears. “Yeah. It means she was sleeping with someone new.” I rub my eyes. “What kind of drugs?”

Joey blinks. “What?”

“What. Kind. Of. Drugs. The coroner?”

Joey shakes his head. “I don’t know. The EMTs mentioned it. Mr. Kim says they’ll know in a few days.”

I sit up and look at him. “What if somebody drugged her?”

His eyes flick across the unmade bed. “Like date rape?” “Maybe. She didn’t do pills.”

Joey shrugs. “Well, even if someone had drugged her for sex, why toss her in the pool?”

I fish around in my bag for sunglasses and put them back on. “Chlorine? Maybe it washes away the evidence. They should at least look into it.”

Joey is silent for a moment. “Yeah,” he finally says. “I guess we’ll know when the results come in.” But I can see he’s thinking now, no longer trying to avoid what I already know.

Maggie didn’t kill herself. She was murdered.

. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.