Prologue

By the time the police entered our houses uninvited throughout the fall of 1991, our mothers had already commanded each of us to tell the truth about Howard Lotte, and we’d already decided to lie. It was too impossible for anyone to conceive, even those of us who had sat with Mr. Lotte and his feckless hands through seasons of weeknight piano lessons, that such a man could commit something so unholy, even if he was a little bit fat. Everyone in Mercury knew which girls had already snitched. We saw what it had cost them. The best hope for the rest of us, we thought then, was to remain anonymous until winter arrived and all the talk turned to idle chatter before it disappeared altogether.

But the gossip about Mr. Lotte would not be squelched, and so the police launched a formal investigation to put the rumors to rest. Making a uniform circuit around town, the squad stopped at the homes of each of Mr. Lotte’s peach-faced, preteen protégés. Some of the homes were split level and some were Victorian, but none of them were trailers. Mr. Lotte didn’t seem to take on

those kinds of girls. Anyone who was anyone took lessons from Mr. Lotte—if you were female, of course.

When each of our turns came to be questioned, the lies spilled out so easily we suspected they’d been planted long ago. There were few girls—seven, to be exact—bold enough to tell the truth, but their soft voiced protests were almost drowned out by those of us unable to defy a town rallying behind one of its own. Though we were just ten, eleven, twelve years old, it became quite clear that men like Mr. Lotte secured a kind of protection that girls like us never could.

The police supplied the questions, and we offered the answers we thought they wanted to hear. Like a swooping she-owl, our voices raised into an echoing chorus as mothers drew the shades for the night and the distant five o’clock bell signaled a shift change at the mill.

Did he put his hands on you? No, Officer. No, he didn’t. No no no no no. The sound found its way to the woods by the edge of the school yard where an old basketball hoop had been torn from the ground and laid prone some time ago, the same spot where lovesick boys dared to press their burning palms against a girl’s. Then the sound moved toward the courthouse at the center of town where Mr. Lotte wouldn’t get the opportunity to appear before a jury of his peers. Our voices only weakened once they reached Mercury’s city limits, where the

highway cut us off from the rest of the world.

Now the town itself haunts us more than Mr. Lotte, even more than our own lies. It seems a story like this couldn’t happen anywhere but Mercury, a place that had become its own needy planet, a town we loved for its empty houses, abandoned buildings, and vacant lots. The people of Mercury liked their trucks, their Iron City beer, and the stench of burning leaves. They knew how to work with their hands—how to sew a quilt, how to fix a carburetor, how to patch a roof. They knew how to wait out a tough winter.

Together we all lived in the afterlife of a city that was once a titan. A very long time ago, Andrew Carnegie evangelized the steel gospel. He followed a simple formula: Contain the coal. Set it on fire. Strip away the impurities. Dispose of the slag.

This was how a legion of unstoppable steel rods was sired. But then came the Steel Apocalypse, and Pittsburgh’s satellite cities didn’t all become ghost towns only because many people had no choice but to stay. Instead, the loss of our lifeblood slowed everything to a pace that was barely detectable, and the era of waking sleep began.

Workers who used to pull twelve-hour shifts in the mill at Cooper Bessemer Steel in the next town over now had nowhere to go. The roads once clogged with commuters became open highways. Mostly, people just sat. And the children, of whom we were some, watched. We remember now how people around town used to float through the amniotic air. Pumping gas. Ordering pizza. Waiting in line at the drive-through ATM. Pushing the shopping cart through the dog food aisle at Rip’s Sunrise Market. Taking long pauses in the middle of sentences. Not bothering to finish them. They used to think nothing could surprise them any more until Mr. Lotte proved them wrong. He proved us

all wrong.

Who are we? We are the girls who lied about Mr. Lotte when others told the truth and most of Mercury hated them for it. We performed for a fickle crowd and lost ourselves in the charade. From the moment we chose to protect a criminal, we also chose to forget everything that had happened. It was our best chance for survival. Even so, our lives were never the same. Our town was never the same.

Our memories threaten to make a scandal of us, so we keep them to ourselves. We still remain in disguise (even from each other), but there’s one thing we know. Our Sunday school teachers had always taught us that an honest answer was like a kiss on the lips, and we were not the kissing kind.

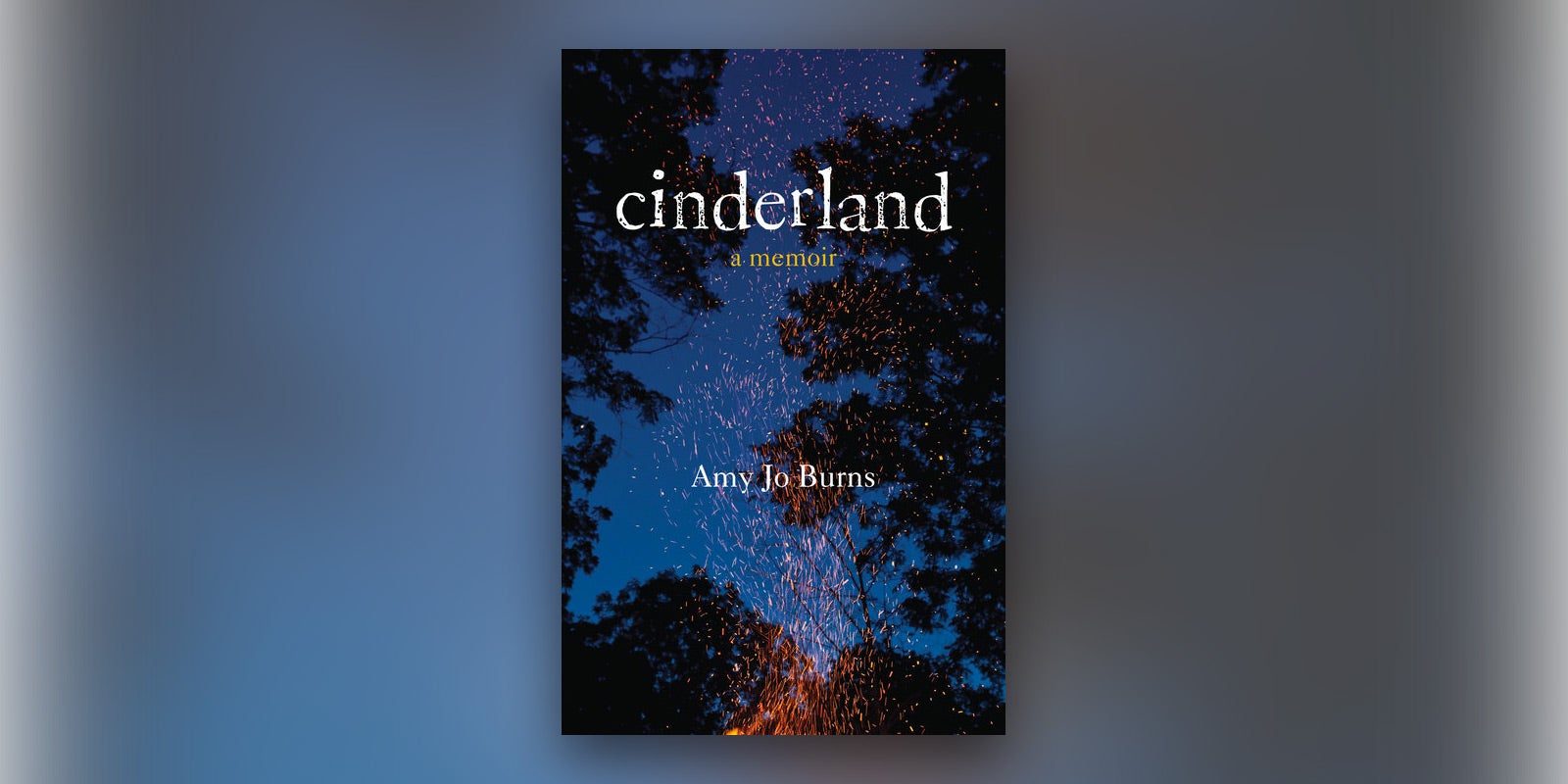

Copyright © 2014 by Amy Jo Burns. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.