1

DENIAL

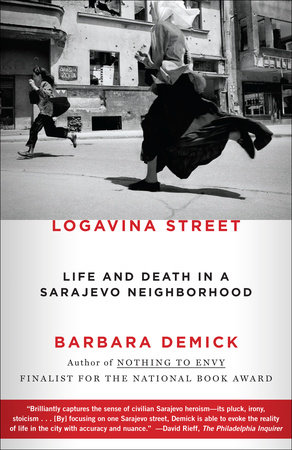

A plaque identifies a mustard-yellow house on Loga-vina Street as the residence and office of Esad Taljanović, stomatolog—dentist. You enter into a formal dining room dominated by a well-polished mahogany table, which is invariably spread with a lace cloth and, in summer, dressed with fresh-cut flowers in a crystal vase. It looks as though the Taljanovićs are expecting guests for tea and scones.

At almost any hour, Šaćira Taljanović, Esad’s wife, answers the door with a fresh coating of pink lipstick, her blond hair brushed back behind a velvet headband.

Esad is a tall, fit man with a confident, white grin, as befits his profession. Whether speaking to a gape-mouthed patient or sitting around the dining room table, he is happy to expound his many theories of politics and culture. But Esad is also willing to admit when he is wrong, and he was dead wrong during the winter of 1991–92, when he declared to anyone who would listen: There will be no war in Sarajevo.

As far as Esad and many of his friends were concerned, war was something you watched on television. Something the old folks reminisced about. Well past the point when they should have known better, Sarajevans found it simply inconceivable that their country would succumb to the lunacy of war.

Throughout the last half of 1991, large swaths of Croatia were in flames. Esad and Šaćira followed developments in the Croatian war from the comfort of their living room, watching the nightly news and reading the papers every morning. As educated people, they naturally were concerned, especially when the architectural jewel of Dubrovnik was attacked. Like so many other Sarajevo families, the Taljanovićs spent summer weekends on the sun-baked beaches of the Adriatic around Dubrovnik. What would become of their summer home? Would they need to cancel their vacations?

The Taljanovićs were not indifferent to human suffering. They were among the first to donate canned goods when a humanitarian organization started a collection for the children of besieged Dubrovnik.

“I can understand how it is that you Americans don’t care anything about Bosnia,” Esad told me gently, as we sat around his still-glossy dining room table in the summer of 1995, three years after war had come to Bosnia. “Here all this shelling was going on a couple of hundred kilometers from here and we were watching like it was happening in the Congo. We were so naïve.”

Most Sarajevans had come of age in a united Yugoslavia, and their naïveté was bred from a lifestyle of creature comforts. Yugoslavia was way off the charts of the Eastern bloc nations, with a living standard approximating that in Western Europe. In ten years of practicing dentistry, Esad and his family had acquired just about every home appliance, from his fax machine to the Cuisinart that Šaćira used to whip up gourmet meals. Although his brother, who was living in Michigan, would regularly send videotapes to show off the American swimming pools and supermarkets, Esad was not envious. He grimaced when he watched the videos. To his eye, Americans looked overweight, unhappy, and alienated from each other and their families.

In Sarajevo, he had everything he could possibly want, with his parents living right downstairs. Practically in his backyard, he had powdery ski slopes that were among the best in Europe and that had made Sarajevo the site of the 1984 Winter Olympics. The clear, turquoise waters of the Adriatic were less than a three-hour drive away. Sarajevo, a city of almost 500,000, had a fine university and medical school for his children when the time came.

As Esad Taljanović appraised things, Sarajevo represented the apotheosis of late-twentieth-century civilization, and civilized people did not murder one another. War was out of the question.

Across Logavina Street, behind a red gate, Zijo and Jela Džino could usually be found in their garden. A spry man of nearly sixty, Zijo was filled with kinetic energy. Jela was broad, but also quick, prone to fits of tears or laughter.

Jela was a worrier, and she had plenty of fodder: the tight pensions she and her husband received as recently retired factory workers; her daughter, who was in the process of moving her family to South Africa; her son, who was working for pocket money in a café and couldn’t decide on a career.

Still, the possibility of an ethnic war in Bosnia seemed preposterous to Jela, even though post-Communist Yugoslavia was disintegrating along bloodlines: Serbs and Croats had been locked in battle since mid-1991 over Croatia’s declaration of independence from Yugoslavia. Her own family typified something that Bosnian president Alija Izetbegović liked to say—that any attempt to divide the ethnic groups of Bosnia would be “like trying to separate cornmeal and flour after they were stirred in the same bowl.”1

Zijo was a Muslim from an old Sarajevo family that had lived in the same house for two centuries. Jela was a Catholic from Šibenik, on the Croatian coast. They had met in 1956 when Zijo was vacationing at a seaside motel. Jela was working there as a waitress. He thought she looked like an actress. She thought he was too skinny, and brought him extra portions of dinner.

When they married, nobody in their respective families raised objections about religious differences between the two, who were so madly in love. A quarter century later, when their daughter, Alma, fell for a nice Sarajevo boy from an Orthodox Serb family, it was no different. Zijo says with a laugh that he thought fleetingly about objecting before realizing “I didn’t have much ground for complaint, since I had married a Catholic.”

About one-third of the marriages in Sarajevo were similarly mixed. Mostly, it meant families had more holidays to celebrate: the Catholic and Orthodox Christmases, the Muslim holiday of Bajram in the spring. For all the blather about ethnicity, everyone traced their roots to the same Slavic stock, and they were virtually indistinguishable in appearance.

Zijo and Jela believed in God but were not concerned with specifics. Zijo disregarded the Islamic prohibitions on pork and alcohol and Jela only attended Christmas Eve mass—which, for that matter, many of her Muslim and Orthodox neighbors also attended. Pre-war tourist brochures boasted of Sarajevo’s historic mosques, Roman Catholic cathedrals, and Serbian Orthodox churches with the same multicultural pride that New Yorkers apply to their ethnic restaurants. Sarajevans’ tradition of religious tolerance dated back to the late fifteenth century, when Sarajevo had welcomed Sephardic Jews who were fleeing the Spanish Inquisition. Zijo’s own father had hidden Jews in a tucked-away room of their Logavina Street house during World War II, even though they lived directly across the street from the Nazi headquarters.

People like the Džinos scoffed when they listened to speeches by Radovan Karadžić, who led the militant faction of Serbs in the Bosnian parliament. Karadžić was making menacing threats about what would happen if Bosnia, still a Yugoslav republic, should follow Croatia and secede. He claimed that it would put Bosnia on a “highway of hell and suffering” that might lead the “Muslim nation to extinguishment,” in his October 1991 speech before parliament.2

Karadžić, a psychiatrist at Sarajevo’s main medical center, Koševo Hospital, was known around town as a goofball. He was an amateur poet and grafter—always obliging if you needed a medical excuse from work or the army if you slipped him some cash. He had served jail time in 1985 for misusing public funds. Nobody could take him seriously.

Moreover, Izetbegović seemed to be bending over backward to accommodate the increasingly militant Serbs. “It takes two sides to have a war and we will not fight,” Izetbegović declared in early 1992.3

Jela was reassured by Izetbegović’s speech. She and Zijo went on drinking coffee in their garden. They weren’t worried. But the truth was that Bosnia was being boxed into a smaller and smaller space, with fewer ways to dodge the impending war.

On June 25, 1991, Croatia and Slovenia declared their full independence from Yugoslavia. Macedonia, another Yugoslav republic, was also stumbling toward independence. That left Bosnia isolated in a stripped-down Yugoslavia—dominated by the biggest republic, Serbia. If Bosnia remained part of Yugoslavia, it would be subjugated under the stridently nationalist Serb president, Slobodan Milošević.

Some Croat politicians suggested that Bosnia form a federation with Croatia. The Bosnians were sure that joining Croatia would trigger a revolt by the Bosnian Serbs, who feared being cut off from Serbia, and outside intervention by the Serb-dominated Yugoslav National Army. Those who had watched coverage of the bombardment of Dubrovnik were terrified of the possible outcome. Other European diplomats suggested carving up Bosnia, but that posed a logistical nightmare since Bosnia was the most ethnically diverse of the six Yugoslav republics. A 1990 census showed that 44 percent of the Bosnian population was Muslim, 31 percent Orthodox, and 17 percent Catholic. With the bloodlines slicing through towns and families like the Džinos, there was no way to split Bosnia into ethnic enclaves without displacing hundreds of thousands of people.

It seemed that the best—if not the only—plausible course of action was for Bosnians to opt for independence. If Marshal Tito’s ethnically diverse Yugoslavia could no longer exist, Bosnia would be the one republic to live out the vision of all religions living together peacefully.

So Bosnia toddled ahead with halting baby steps toward nationhood, unaware of the forces assembling to shoot it down. Over the weekend of February 29–March 1, 1992, voters answered a referendum question: “Are you in favor of a sovereign and independent Bosnia-Herzegovina, a state of equal citizens . . . of Muslims, Serbs, Croats and others who live in it?”

The response to the referendum was a nearly unanimous “yes,” although only 64 percent of eligible voters participated. Karadžić had declared a boycott of the election, and in many Serb-controlled districts voting was not permitted to take place.

Ekrem and Minka Kaljanac were decidedly apathetic about politics. They lived on the second floor of a small, nondescript apartment house on Logavina Street and had their hands full, raising two rambunctious boys. Ekrem moonlighted at various jobs to make ends meet.

Ekrem and Minka, having come of age under Communism, were deeply distrustful of politicians and hadn’t bothered to vote in 1990 when Bosnia held its first free parliamentary elections. But on the day of the referendum, they were among the first to vote. “I voted because I didn’t want war. I thought by voting for an independent Bosnia we would be showing that we all wanted to live together,” Minka explained.

A few days after the referendum, Serb militants blocked the roads in and out of Sarajevo. Five student demonstrators were killed removing the barricades. But that would be the last of the violence, Ekrem was convinced. “I was positive about the cohesion of Sarajevo. Positive. I was certain it couldn’t happen here,” he said.

Ekrem and Minka are not easily fooled. Although neither is a university graduate, they are acute observers of their environment. They are street-smart. Minka is a thin, shy redhead. Her good looks are only marred by the ravages that war has taken on her teeth. Ekrem has a taut carriage and darting blue eyes, always challenging you with a measure of suspicion. He later became a cop.

Ekrem’s unwavering confidence in Bosnia’s future suffered its first blow on a business trip to Belgrade, where he was installing a heating system. Ekrem was driving home at 5 a.m., in heavy rain, when he found himself rerouted onto a back road by an unexpected police checkpoint. The road led him into the mountains, and he was surprised to see cadres of soldiers conducting some sort of training in the hills. They seemed to be part of the Yugoslav National Army, but many of the soldiers had longish hair and beards, not the usual close-cropped military cuts.

A commander ordered Ekrem to speed up and get the hell out of there. Ekrem pressed the gas pedal of his Renault to the floor in his hurry to get back to Sarajevo and tell Minka what he had seen. “We were both frightened. My skin was crawling. I knew there was something evil in the air,” Minka recalled.

What Ekrem had observed, without quite comprehending its implications, was the vast military buildup in the mountains that would choke off Sarajevo from the outside world.

Karadžić’s followers had declared large chunks of Bosnia “Serb Autonomous Regions” in 1991. The Serb regions had set up their own parliament and on March 27, 1992, declared a “Serb Republic.” They were training “Chetniks,” Serb irregular fighters. The Chetniks wore beards and patches on their jackets with a skull, eagle, and crossed swords.

At the same time, Yugoslav National Army troops were advancing from Serbia into Bosnia. Their officers claimed they were there to keep the peace if the situation got out of hand.

As March dragged on, Ekrem witnessed several other disturbing events. At Koševo Hospital, where he was doing a utility installation, he noticed that a number of his Serb colleagues were unexpectedly leaving town. One man, Grujić, said he had bought a new car in Serbia and was going to pick it up. Another coworker, Dragan, said he was going to do some work at his vacation house. Milutin announced he was off to take hunting classes for a month. He was later caught as a sniper.

Meanwhile, the foreign ministers of the European Community were planning to convene in Luxembourg, to recognize Bosnia as an independent state. They hoped it would stall the momentum that was building toward war. The meeting was scheduled for Monday, April 6.

Back in Sarajevo, it promised to be a lively weekend. Delila Lačević, seventeen, and Lana Lačević, eighteen, were off for their usual Friday night excursion to the Baščaršija, the downtown Turkish quarter laced with narrow alleys of cafés and souvenir shops. Delila, curly-haired with a mischievous grin, and Lana, tall and husky with short-cropped blond hair, were cousins and best friends. The two families—their fathers were brothers—shared a rambling old house on Logavina at the uppermost end of the street. Lana and Delila spent the evening at their favorite hangout, Alo, Alo, where they stayed out late, gossiping about boys and the latest hits on MTV.

When they arrived home they were greeted by their angry, anxious parents. There had been a shooting in Baščaršija, and someone had been killed. They were taken aback to be chastised; both were responsible girls, both planning to be doctors like Lana’s mother, Šaćira. They were shocked to learn of the murder. Such incidents were rare in Sarajevo, even though the city had been the scene of one of the most famous murders of all time: the 1914 assassination of the Austro-Hungarian archduke Franz Ferdinand, which sparked World War I. The Lačević families nervously locked their front gate and went to bed.

Saturday, April 4, a policeman stopped by the Lačević house with more unsettling news. He said that Chetnik irregulars were stirring up trouble, erecting barricades around Sarajevo. Despite the palpable tension, relatives came over to the house for coffee and cakes. As Lana went to close the gate after them, at about 8 p.m., she saw beautifully eerie streaks of red light dancing in the distant hills.

“Mother, come look at what’s going on!” Lana called out. She thought she was watching a fireworks display for Bajram, a Muslim holiday that began that weekend.

Šaćira Lačević yelled at her to come back inside. The lights in the hills were tracer bullets.

Copyright © 2012 by Barbara Demick. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.