1 AQUINCUM

Look back over the past, with its changing empires that rose and fell, and you can foresee the future too.

—Meditations, Marcus Aurelius (121–180)

A pair of fossilized footprints of a Paleolithic woman and a child, left around 30,000 years ago, were found in the summer of 1994 beneath one of the principal thoroughfares of Buda, Fõutcá (Main Street), by the Danube. It was unearthed by a contractor digging up the road and prompted a wave of interest and debate among Hungarians about the far-distant past. For children educated under forty-five years of Communism, and to earlier generations brought up under regimes of the Nationalist Right, the history of Hungary began in the ninth century AD when the nomadic Magyar tribes, who originated from the Kazakh steppes, wandered west and began settling in the Danube basin. Before that, the narrative went, the area was almost empty, virgin territory. The stones of Budapest have always been political; each new discovery of life before the Magyar ‘conquest’ has begun a new round of culture wars about who was a Hungarian, when and where. Over the years, various archaeologists made finds nearby of a Bronze Age civilization along the Danube, locating tools, weapons and pieces of gold dating from more than 3,000 years ago. During the eighth to the fifth century BCE the nomadic Scythians, originally from central Asia, built temporary villages in present-day Budapest. One of their off shoot tribes were the Pannons.

Proof of the first semi-permanent settlement was made in the mid 1990s: a fort built around 550 BCE on what is now Gellért Hill, on the northern reaches of Buda, by a Celtic tribe known as the Eravisci. It had a commanding view of the great sweep of the river. Little is known about the Eraviscans or their language, but it is believed they called their tiny settlement, on mineral springs perfect for bathing, ‘Ak-Ik’,* meaning warm water. Budapest has always been a spa town. The land further east, present-day Pest, on the other side of the river was occupied by the Sarmatians – the Danube was a natural border, hard to cross. But they built no permanent settlements in the region.

In the early part of the fi rst century AD the legions of the first Roman Emperor, Augustus, made short work of conquering and subjugating the Eraviscans. The Roman army arrived in force from around the year 50 and began work on building a defensive line of forts along the river to patrol the empire’s newest province: Pannonia. One of the first of the camps, originally occupied by a corps of cavalry, was named Aquincum – because of the hot and cold water springs below what are now the Buda Hills. Around the year 90, the Romans reinforced the settlement and began to build a significant camp for the legions. Aquincum was the headquarters of the Legio II Adiutrix, the main army of defence against ‘barbarian’ raids from the North and East. A large civilian town grew a kilometre or so from the camp comprising a variety of traders and artisans to serve the military – along with a large number of slaves.

In 106 the Emperor Trajan made Aquincum the new capital of the province, which he renamed Pannonia Inferior – Pannonia Superior was further west, where its principal town was Vindobona (now Vienna). An enormous 120-metre square palace for the governor was built on the Danube island opposite, now Óbuda island. The fi rst of the Aquincum proconsuls to live in the new palace, governor from 106 to 108, was Publius Aelius Hadrianus, who a decade after he left Aquincum would become the Emperor Hadrian. Almost nothing, sadly, remains of the building. In the late 1940s the Soviets, during the early days of their East European empire, laid the concrete foundations of a shipyard over it, but from surviving drawings, a few mosaics, and models it must once have been an extraordinary building.

When troop numbers increased over the next decades, a second legion was stationed there. Eventually, by the third century, there were four – to quell the rising number of barbarian raids. The Emperor Marcus Aurelius stayed frequently in the military fort at Aquincum and the best evidence is that he began writing his

Meditations in 167, while in the town but not actually on battle manoeuvres at the front. He certainly wrote parts of the work at Aquincum – perhaps even the aphorism so appropriate to the history-conscious Hungarians: ‘Look back over the past, with its changing empires that rose and fell, and you can foresee the future too.’

Aquincum grew into a large settlement, with central areas designed by well-known Roman architects. It became a significant Danube port, the centre of large-scale river transport. It had an enormous amphitheatre for games that could seat around 12,000 people. It was bigger in area than the Colosseum in Rome though its seating capacity was much smaller. (The Colosseum could seat 80,000.) It had animal pens to supply lions and other beasts for sacrifice and, for the time, a state-of the-art watering system so it could be flooded for the mock sea battles with model boats that the Roman audiences loved so much.

Disaster struck Aquincum around 170 when the Antonine Plague reached the town. Hundreds of thousands of people throughout the Roman empire perished from a pandemic of an unknown disease (now thought to be a variant of smallpox) that ‘ate up the body, causing coughing fits, destroying the lungs and other organs’ according to the Greek physician Galen, who treated many victims during three waves of the plague. The pandemic hit Aquincum hard. Perhaps as many as a quarter of the fort’s legionaries died in the pandemic. But because of constant enemy incursions and its proximity to Italy, the garrison was thought to be of such strategic importance that reinforcements were sent as a priority.

Pannonia possessed significant political clout in the empire as a springboard for gifted and ambitious men. In 193 – the so-called ‘year of five emperors’, as civil war nearly ripped Rome apart – it was the Pannonian legions’ declaration for the Senator Septimus Severus as Emperor that filled a political vacuum and began a reign of eighteen years which brought renewed prosperity and a measure of stability to the empire.

Septimus Severus had been governor of Pannonia a decade or so before ascending the throne and a year later, as a reward to his supporters in the province, he upgraded Aquincum into a

colonia. This meant much more than mere status. It turned the town into a major provincial capital city and made an increasing number of its formerly Celtic population into full Roman citizens. For the following century, Aquincum boomed. A civilian area a couple of kilometres from the military base,

nestling by the banks of the Danube, grew fast. At its high point the population was around 40,000, large by Roman standards, mostly comprising army veterans and their families and Romanized Celts. This was Hungary’s first full-scale city. It would be around 1,500 years before as many people lived there again.

If one looks, there are still plenty of reminders of Roman Buda. At one of the city’s major transport hubs, Floriánter (Square), amidst a bus terminus and a spaghetti junction of roads and underpasses, are the remains of a huge thermal baths complex that must have been as impressive as anything the Ottomans or the Habsburgs built later. There is a reminder, too, of an earlier musical city. Near the baths in the 1990s archaeologists found a richly decorated tomb chest of Aelia Sabina, the wife of the military camp’s chief water organist, one of the most important musicians in the town, that bore a moving inscription: ‘Enclosed within this stone lies Sabina, dear and faithful wife. Excelling in the arts, she alone surpassed her husband. Her voice was sweet, her fingers plucked the strings. But she fell silent, suddenly snatched away. She lived three decades, five years fewer, alas . . . She herself lives on.

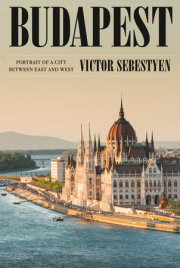

Copyright © 2023 by Victor Sebestyen. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.