1

Black Is Beautiful

Hard times require furious dancing. Each of us is proof.-Alice Walker

Black is beautiful. Popularized in the 1960s and '70s, this phrase encompassed a broad celebration of Black culture and identity. It urged the recognition of a valuable legacy and fostered a sense of pride in contemporary accomplishments. It also focused on the Black community's emotional health by changing beauty standards and affirming natural aspects of who we are and how we show up in this world.

Today, more than half a century later, the phrase bears repeating for a new generation of children who may not have gotten the message the first time around. Black culture is indeed beautiful. The beauty shows up in more ways than can be covered here (or anywhere, really), but children can find some vibrant facets in Black literature.

Culture is the way of life for a group of people, including customs, arts, achievements, social norms, language, and values. Cultures shift over time and can be experienced differently across generations, but the most closely held or valued parts of a culture are generally preserved even amid outside influences. This is true of people everywhere, and it's especially true of African Americans, as our culture is situated within the landscape of American society.

American and African American cultures are distinct but related. We easily understand the interrelationship when we watch how quickly music originating in the Black community is embraced and emulated by the mainstream scene, with or without credit. It's also apparent when witnessing the similarities between some aspects of Southern comfort food and the narrower designation of authentic soul food. While overlap is acknowledged and expected, Black Americans proudly preserve a distinct culture that has evolved over many generations and hundreds of years.

Relationships and geography impact the degree to which a person associates with, embraces, understands, or even recognizes African American culture. This makes sense when we consider that cultural exposure is one of the greatest influencers of cultural adoption. The more time someone spends immersed in our culture, the more opportunities they gain to learn the unique aspects that make us who we are. Family relationships, close friendships, and community ties help build awareness and comfort, making belonging easier to come by.

Some children are immersed from birth. They know what it means to be surrounded by people who understand the nuanced attributes of their culture, and they recognize the pieces of their lives that are firmly tethered to the African American experience. These kids have a solid attachment to their Black families and communities, and parents often (and sometimes mistakenly) assume they don't need anything more to help them embrace who they are.

Other children aren't exposed to African American culture beyond what they may catch on television or overhear in a conversation. These children often must rely on stereotypes, assumptions, and misinformation to fill gaps in their understanding. While they may grow after leaving home and interacting with a more diverse group of people in college or through work, they're generally left to their own devices.

Most children fall between the two ends of the spectrum. They have some understanding and exposure to Black American culture but haven't had enough experience to comprehend its fullness. These kids, and often their parents (including Black parents), don't know what they don't know, making it difficult to move forward. They're open to learning more; some may even long for a deeper connection or more context. They need opportunities to learn from and connect with Black voices to help them align what they already know with new inputs.

Personal relationships are the most effective way to meet children's need to explore our culture. Whether close ties are formed through familial or significant community interactions, the more a child is immersed in authentic and varied relationships with Black people, the more they will naturally understand.

Geography can significantly influence children's opportunities to witness and experience Black American culture, but it's also generally locked in. And sometimes, even the perfect confluence of people in just the right place still isn't enough. When children need and long for more, sometimes a fantastic story is just about the only thing that will hit the spot.

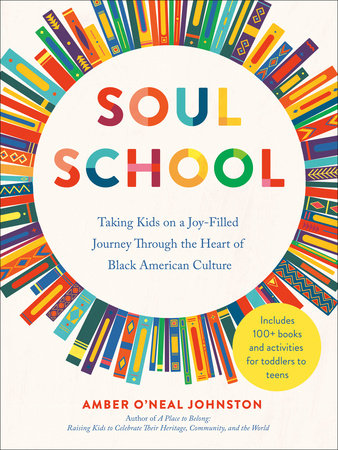

In my book

A Place to Belong, I spoke extensively about using literary mirrors and windows while curating a home library. A mirror is a book that helps build a child's identity as it reflects their own culture or personhood. Children find themselves represented along with their families and communities, and their sense of belonging grows as they recognize characters like themselves moving through the world. Books as windows, on the other hand, provide a realistic view of how others live while simultaneously situating children within the context of a wider world. Providing books that give honest and varied views of different people's lives is like pulling back the curtains of a darkened room, allowing light to pour in.

Literature can be a fun and accessible tool for kids as they grow in their understanding of and love for Black American culture. Mirrors help Black children already comfortable in their skin feel validated and valued. For kids with limited exposure to African American culture, the same stories serve as windows, providing details they don't encounter elsewhere. In either case, children recognize and learn from disparate yet harmonized Black voices delivered across time and place.

These pages celebrate the beauty of Black American culture. Through entertaining tales smothered in caramel, dipped in chocolate, and sprinkled with Black Joy, our kids will examine cultural elements intrinsic to the Black experience via words and pictures penned and drawn by Black hands.

Song and Music

Every culture has its own music. But the sounds of Black America are so recognizable, and the emotions they invoke so visceral, that it's impossible to define our culture without granting particular attention to our music. Our ancestors brought their music to America, and it survived because it was housed inside their bodies and could not be stolen. If I ever questioned how closely linked our immersive styles of Black American song and music are to that of West Africa, a trip overseas made me a believer. While visiting Accra, Ghana, with my children, I was keenly aware of the rhythms surrounding us at every turn. Though it was my first time on the continent, the music made me feel like I'd been there all along. I recognized the call and response, improvisation, and accompanying body movements. I saw a clear and undeniable connection between the music of the Motherland and the music I grew up hearing, and the correlation moved me.

Born of the music carried from Africa, combined with unfamiliar and traumatic experiences, enslaved people formed spirituals, a new genre of music. Some were work songs, while others were biblically rooted, and all were passed along orally in the folk tradition. Wisely, these songs were often used to communicate outside the bounds of the enslaver's understanding, especially when instructing freedom seekers. At other times, the spirituals helped enslaved people stand up under the heavy burdens of captivity as forms of creative resistance, self-expression, worship, or recreation.

Created by "a circumscribed community of people in bondage [spirituals] eventually came to be regarded as the first 'signature' music of the new American nation." The sacred tradition of these spirituals evolved into gospel music. Spirituals were communal, carried forth orally by unknown composers, and fostered under group ownership. In comparison, Black gospel grew out of urban Northern churches in the 1920s to 1930s with recognizable artists and styles based on hymns with improvised and "bluesy" influences. Rich solos and intervals of enthusiastic worship were often embedded in this style.

As gospel grew and developed from the sacred side of the spiritual, its protest and social traditions birthed an eclectic mix of Black musical expression. Freedom songs, blues, jazz, rock 'n' roll, soul, funk, rap, and hip-hop grew from the roots of an unparalleled cultural and musical African American heritage. When we speak of baseball and apple pie, we can proudly include African American music in the fiber of Americana. Indeed, the familiar sounds that undergird nearly all folk, religious, and popular music in this country would not exist without it.

Often imitated and appropriated, Black music in the United States is frequently seen in an adulterated state. Our children should know and appreciate authentic sounds and learn how they came to be. Given the incredible influence of our music and its infectious and "marrow-deep" (per Wesley Morris) legacy, there's no doubt that music should have a refrain in the books our children enjoy.

Cuisine

Whenever I write about our food, I get caught up in the sights, sounds, and smells. I envision a table filled to the brim with an obscene amount of delectable dishes. How can I describe soul food?

According to Sheila Ferguson, author of

Soul Food: Classic Cuisine from the Deep South, it's just what the name implies. "It is soulfully cooked food or richly flavored foods good for your ever-loving soul." But there's more to it than that. "It is a legacy clearly steeped in tradition: a way of life that has been handed down from generation to generation, from one Black family to another, by word of mouth and sleight of hand. It is both history and variety of flavor." This history, legacy, and flavor set soul food apart from the broader designation of Southern cooking.

In his book

Soul Food: The Surprising Story of an American Cuisine One Plate at a Time, culinary historian Adrian Miller describes a traditional dinner: "entrées (fried chicken, fried catfish, or chitlins); sides (black-eyed peas, greens, candied yams, and macaroni and cheese); cornbread to sop it up; hot sauce to spice it up; Kool-Aid to wash it down; and a sweet finish with a dessert plate of banana pudding, peach cobbler, pound cake, and sweet potato pie." Yep, I'd say that sums it up nicely.

But while Miller chooses not to focus on regional cuisines, I would add the many famed soul food dishes of Louisiana's celebrated Creole cuisine, the Chesapeake Bay area's seafood-centered menus, and the legendary Lowcountry cooking of South Carolina and Georgia. I'd also describe well-seasoned vegan and vegetarian dishes of Black American kitchens that long preceded current plant-based trends. And no list would be complete without grits, okra, biscuits, ham hocks, neck bones, and, of course, sweet tea. I've lived in the American South my entire adult life, and I promise you that Black folks take their sweet tea very seriously.

Black Americans feast as an outpouring of love and a means of connection. One of the quickest ways to offend an elder is to refuse her cooking. Both sets of my grandparents lived on the same street, just a few blocks apart. When visiting, we'd sleep at one house, wake up, and enjoy a breakfast of scratch-made biscuits, fried potatoes and onions, thick-cut country bacon, and savory grits with a hint of garlic.

After sitting for a sufficient amount of time, we'd make our way down to the other house, for an entirely different meal of sliced ham, smoked sausage, buttermilk waffles, and more biscuits smothered with gravy. Learning to eat just enough at both homes to avoid offending either grandmother was a sport my siblings and I trained in from our earliest years. Navigating Black kitchens (and grandmothers) is an art.

We show our care for one another and our guests through delicious food. Our cuisine is the heartbeat of gathering times, whether Sunday dinners, church picnics, family reunions, weddings, or funerals. Food laces life's valleys as we share during illness and hard times, just as it plays a starring role in our most joyous celebrations. And it fuels our playful competitive spirits as we tease and jest over who makes the best thus-and-such and argue about which cousin can best re-create so-and-so's famous dish.

Black American cultural food is well seasoned, meticulously flavored, and lovingly savored. It's as much a part of who we are as our music, and teaching children to recognize and honor it involves much more than just recipes. They have to get the feel of it, the energy and emotion behind the dishes, and the history of a people whose creativity turned scraps into delicacies. Kids can soak up this understanding from words and imagery as they hear stories from Black kitchens teeming with life.

Visual and Performing Arts

The design and style aesthetic of Black American art is expansive. To box it into a tight space is to disregard the gifts and work of generations of artists. There's no artistic style that children need to imagine as singularly representing our culture. Instead, exposure to the movement and images conceived by Black faces, hands, and bodies will give them a steadfast appreciation for the creativity pulsing through our art.

Dance, music, and theater fueled some of our most defining eras, including the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s and 1930s, during which Langston Hughes wrote, "We younger Negro artists who create now intend to express our individual dark-skinned selves without fear or shame. If white people are pleased we are glad. If they are not, it doesn't matter. We know we are beautiful. And ugly too... If colored people are pleased we are glad. If they are not, their displeasure doesn't matter either. We build our temples for tomorrow, strong as we know how, and we stand on top of the mountain, free within ourselves."

Much like oral song, other performing arts traveled across the Atlantic and made their way into drum circles, cake walks, and pattin' juba (aka hambone, the slapping of hands, legs, arms, chest, and cheeks to create complex rhythms) on slave labor camps. These forms of entertainment, along with other instrumental performances, accompanying dances, and dramatic recitations, paved the foundation for today's collection of Black American arts across our nation.

My family once visited a museum exhibition called

The Dirty South: Contemporary Art, Material Culture, and the Sonic Impulse. Unlike anything we'd previously witnessed in a traditional art museum, it captivated my children's attention, from the oldest to the youngest. The works highlighted the contributions of the American South and Black culture to the art world while showcasing how critical they are to comprehending America's past, present, and future. The curators told a story of Black genius, through sculpture, painting, drawing, photography, film, and visual imagery. It gave necessary due to African American works often relegated to the back of the room in favor of "real" art.

Afterward, my oldest daughter began to see how she could use mixed media to define art on her own terms. Within months, she'd created a large-scale collage featuring pages of literature, broken porcelain, flea market antique jewelry, floral imagery, and old photographs of Black women. One of her Black handmade cloth dolls is affixed to the center of the wood-backed piece. She entered the work in a competition, and on the tag for the judges, she wrote, "I designed this doll entirely from fabric scraps as the centerpiece to this vintage-inspired work that imagines generations of women who enjoyed tea parties with dolls just like her."

Copyright © 2025 by Amber O'Neal Johnston. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.