1

The night Ralph’s mother flayed her forearms, a woman in a red dress handed him a business card. I know how woman in a red dress sounds because I thought the same thing at first. When I got back to the ICU waiting room with our sodas, I said, what do you mean woman in a red dress, a Jessica Rabbit type came va-va-vooming down the hall, pendulum hips pounding sound waves into the souls of dicks?

Christ, said Ralph. No. He cracked his soda and took half of it down. The dress was floor-length, thick cotton, a chaste cream turtleneck underneath. She would bring ambrosia salad to a church potluck, you know what I mean? Secretly hates her nephews, never swims in public. Would definitely take in and gaslight a feeble sister.

I frowned. What do you know about ambrosia salad?

I know it’s got marshmallows. Isn’t that enough? Then he paused, still hitched to the red-dressed woman’s memory: nice hair, he said, more to himself than to me. Very—he searched for the right word—muscly braid, hanging in front of her shoulder all the way down to her waist. White-blond, but not fine. Fuzzy around her face. And those eyes.

What about her eyes?

He started with how the woman had glided up to him, gently, as though he might spook. And he might have, absorbed the way he was: elbows on his knees, fingertips together, mesmerized by the slow jellyfish motion he made with his hands. The card appeared in front of his face, and with a whispered spell, Thank you, sir, it was in his hand. He looked up, seized so completely by her bottomless brown eyes that the waiting room’s relentless torments—flickering fluorescents, tacky surfaces, cast of swollen-eyed kin—evaporated completely.

Then I arrived with the sodas.

Soda because if either of us has more coffee, our colons are going to disintegrate. But we need caffeine, have to stay awake. Poor Ralph isn’t leaving this hospital until he knows for sure whether his mother is going to make it. There would be no go home and get some rest for Ralph; no we’ll call you when we have more information. Ralph just wasn’t that kind of son.

“Bottomless brown eyes,” I repeat, wincing as I open my can, a mysterious habit with an origin I’ve buried for good reason I’m sure.

“They were strange. Almost frothing.” I sip my soda, slurp the rim. “Brown hot tubs.”

He frowns. “You’re thinking about diarrhea.”

“Well, obviously, Ralph. You’re thinking about diarrhea too.”

“Only because I know that you are.”

“Perfect body temperature, thick enough to hold you. Might actually be better than water.” He admits with a shrug that it would be nice to sag nearly suspended, perfectly warm, in a pool of slack shit. “It would have to be ethically sourced, of course.”

“Of course. Completely voluntary.”

“Naturally. Oh, except . . . well, I don’t know.” He sinks in his seat, starts to bring his hand to his chin, then thinks better of it, reminded by the conversation, perhaps, of all the bodily fluids that’ve passed through these rooms. A sensible instinct that I’ll now try to keep in mind for myself.

“What?”

“I mean, do we want to lounge in the feces of someone who’s old enough to consent to it?”

I shift into the soothing articulation of mutinous AI: “Ethically extracted from exclusively breastfed infants, ORGANICA baths are available in three therapeutic densities, and—” I stop, struck with the realization that hot tubs are essentially artificial wombs: our bootleg attempt to revisit that safest, most perfect, capital-H Home, and therefore the worst imaginable thing to be describing to someone whose mother is currently dying. I set my soda down on the side table, drag my hands down my face.

“You really shouldn’t do that in here,” Ralph warns.

And of course he’s right, I’ve forgotten already. I rub my hands on my thighs instead, cleansing them against the exfoliating grain of the denim.

“Maybe we should get a hot tub,” I suggest, a gently used surrogate with deep, jetted seats and a marbled liner.

“I don’t know. Seems like a whole culture.” He whispers the word culture.

“Culture,” I mimic him. “Pervert culture.”

“Plus they’re expensive. And where would we find all that human shit?”

He smiles, blows a little laugh from his nose, then glances warily at the mechanized double doors, which would, sooner or later, wheeze open with information about his mother. His genuine love for her is evident in his expression right now, the muscles of his mouth and forehead clenched, anticipating the loss already, all the luster leeched from his skin.

Her depression had become, it sounds awful to say, just so grating in the days leading up to this: cloying and relentless, with no end in sight as far as she was concerned, having refused all forms of medication and therapy, but now that she was quiet, now that she might be gone, Ralph was being pummeled by the full typhoon of his love for her, one of life’s cruelest tricks, that the extent of this love waits to reveal itself.

I burrow beneath his arm and he pulls me into him, my length along his, ear against his chest, the top of my head grazing his jaw. I draw his hand to my mouth, take a nip of his skin between my teeth, try to suck the sadness from his pores like venom. He shakes it free as he always does when he’s not in the mood for my biting and drinks more of his soda.

Humans like to put their mouths on the things they love. I remember seeing two mothers on the subway once, babies wrapped snug to their chests with their sleep-soft mouths gaping skyward. “Have you chewed on her feet yet?” one mother asked the other. “Oh, God, yes,” the other mother replied.

I imagine the gentle pressure I’ll apply to my own baby’s foot one day, practice longingly on my bottom lip, the bounce of her new flesh between my teeth. And how she’ll look at me without recoiling, letting me because she doesn’t know any better. She won’t even realize that we’re not the same person, not for a while.

I’ll encourage Ralph to have a bite, and he’ll be just delighted. Though he likes their necks best, protected by the pressed flesh of cheek and chest. He likes their translucent fingernails too; the indents of their knuckles and knees; how quickly their profound suspicion becomes puzzled amusement becomes wriggling joy.

I’d chew on Ralph’s feet if he’d let me; if it’d soften the razor-sharp edges of what he’d just seen: his own mother, still as seaweed, washed up on the basement carpet, which was so saturated in blood that it squished beneath his feet and wrung pale around his knees when he slid to her side. No, no, no, no, he muttered, fumbling for a pulse, relieved to find the gentlest vein still whimpering in her throat.

He screamed, CALL AN AMBULANCE! So I did, right away, without asking, without thinking. They said, Nine one one, what is your emergency? And I said, I don’t know! I hollered down to Ralph, Ralph, what happened? And he shouted back, Mom’s had an accident, there’s blood everywhere, so that’s what I told them: My mother-in-law’s had an accident. There’s blood everywhere! Maybe Ralph didn’t realize at first what’d happened, thought she’d accidentally snapped her veins against that kitchen knife’s cold blade.

A short while later a team of paramedics marched in and, with the orderly calm of ants, strapped her to a gurney and pulled her up the stairs. The ceaseless squeal of their bloody boots against the hardwood, the hymnal repetition of their internal communications, Ralph and I helpless as ghosts. We followed them out the front door, watched them slide her into the back of the ambulance. “We’re right behind you, Laura!” I shouted, and one of the paramedics nodded at me, as if to let me know that’d been the right thing to say.

And Ralph’s reactions to everything up until this point had been predictable because they were always predictable. Ralph Lamb had never contained a single surprise in his whole life. He was grief-stricken on the way to the hospital, as anyone would be, anxious while they worked on her in emergency, as I was—all the understandable and expected behaviors of a devastated anyone.

But then the doctors finally emerge to tell us that they haven’t managed to save her. They tell us that we need to make arrangements with a funeral home. That they’re very sorry and they did all they could, and do we want the clothes she was brought in? And Ralph, again quite predictably, nods, yes, please, and accepts a clear plastic bag containing her bloody housecoat and nightgown the way a child handles a goldfish won from a carnival, steeled by the magnitude of what’s been passed to him. He brings the bag to his face, evaluating its contents: fabric dense and red and wrinkled as placenta. And that’s when he, quite unpredictably, hands me the business card from the woman in the red dress. “Can you drive me here?” he asks.

I look down at the card. I don’t understand what he’s talking about at first. Cheap white stock, black writing you can feel beneath your thumb: Find out why.

I stretch my lungs with a gulp of overprocessed hospital air, hold it till I can figure out what to say, but nothing comes.

“Turn it over,” he says.

I exhale with emphasis. There’s an address on the back, not far from the hospital, along with a picture of a single, lashless eye: almond shaped with a circle and a dot in the middle. I realize that the woman in the red dress with the bottomless browns and the ambrosia salad recipe is a seer—a medium or a psychic or whatever they prefer to be called. I assume they must have a preference, in which case that should really be on the card too. What if we call her the wrong thing and she takes offense and blinds us both with a spell?

I blink at the card for a moment until a man coughs and I remember that it’s late, and there are other people in this ICU waiting room: swollen-eyed kin with their feet out, pinching blankets beneath their chins, trying to make their cumbersome bodies comfortable but also polite, aware that if they’re lucky, in a little while they’ll lose consciousness, sink, spread, off-gas like great snoring molds, beyond reproach.

Everyone is horizontal-ish except for one woman, maybe a hundred years old, peering so deep into nothing that it has to be something. Some thing. Every flap of the woman’s flesh—lips, ears, nostrils, eyelids—curls inward. One of her unblinking eyes is as cloudy as Ralph’s mother’s engagement ring, an oval opal, set in four diamond prongs and an elegant gold band, thin as a hair. She’d promised to give it to Ralph one day when he was ready to propose to someone, but when I came along, and he was ready to propose, she didn’t want to anymore, didn’t think it suited me and maybe Ralph should check out Kay Jewelers in the mall because Irena had told her they were having a pretty significant sale.

She’d been wearing it tonight when she died. I noticed a plump of blood had parted around it, connecting again at her cuticle, restored, dripped whole from her fingertip. The ring was still shimmering despite the mess, commanding the respect of so much blood.

Ralph and I, we were going to have a baby soon. Soon, soon, soon. Maybe a girl, who’d be proud to inherit her grandmother’s ring, or a boy, who might love someone so much one day that he’ll want to claim them with an heirloom. Selfish not to, Abby, think of the children, Abby. And an impulse, raw and manic as lightning, screamed through my nerves, sidled the ring up off Laura’s bloody finger, and thumbed it deep down into my pocket while Ralph continued to pace, to mutter no, no, no, no, no, no, nos, behind stiff hands, blinders, pressed against his temples.

Right away hot, frantic guilt snatched my chest. The impulse cackled, climaxed and drowsy, distracted enough for me to quickly pull the ring back out of my pocket, start to force it back onto Laura’s uncooperative hand. But then the front door banged open, the paramedics thundered down, Ralph stopped muttering and turned to me so I had to hide it again, first in my palm then back into my pocket, the mischievous impulse satisfied, cackling harder as it fluttered away.

Back in the ICU waiting room old Opal-eye blinks, turns her head, fixes her gaze on me, like she knows what I did, what’s hiding in my pocket, and a cruel thought violates the folds of my mind, residue left over from the evil impulse: I got the ring anyway, Laura, it’s mine now, isn’t it, now that you’re dead. I press my pocket, feel the ring’s undeniable there-ness. I need to close myself off to mischievous impulses and bad thoughts. But it’s hard because no one ever taught me how.

“Can you drive me?” Ralph repeats. I’m still transfixed by the card. Find out why. Find out why. No, I think, no, I can’t drive you to this quack who’s going to take all the cash in your wallet, lie to your face, and play with your pain. And in his right mind, Ralph wouldn’t want me to either. In his right mind, he wouldn’t have given this card a second thought; he’d have taken it to be nice of course, because that’s the kind of person he is, but then he’d have thrown it away or, more likely, slipped it into his wallet and forgotten about it until it was time to get a new wallet, find it again one day when he was emptying this one and feel low, drift back to this terrible night in the fluorescent ICU and into the bottomless browns of the woman who’d given it to him. I’d ask him what was wrong and he’d tell me what he’d found. I’d make him his favorite dinner from Secrets of a Famous Chef—chicken à la king—and give him a nice, enthusiastic blow job before bed.

“Oh, Ralphie,” I say, and pull him close and hold him and start to cry, my poor baby, feeling every bit a thirty-one-yearold orphan. But he’s not crying with me. He’s assumed the posture of a human cannonball: arms stiff and straight down his sides, chin tucked in like a braced nut sack.

I let go and look him over, sniff the sobs back into my head as though saving them for later.

“Okay, listen, I just have to say for the record.” I look around at whatever invisible entity stirs to attention when somebody says that, careful, though, to avoid the old woman’s knowing opal eye, which may or may not still be fixed on me. “I don’t think this is a great idea. You have no idea who this woman is, Ralph, you have no idea what’s waiting for you here.” He stares at me, wide eyes battered, exhausted, definitely about to ask me again in the exact same way, I know, but can you drive me? And I can’t bear to hear it, honestly, if he asks me that way one more time, I’ll scream, I really will, scream and startle all the melting, gaseous molds in this waiting room so they sit up and blink at me and shake their heads. “But if this is what you want to do right now, then, yes, I can drive you.”

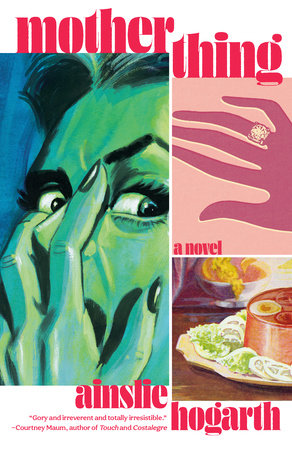

Copyright © 2022 by Ainslie Hogarth. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.