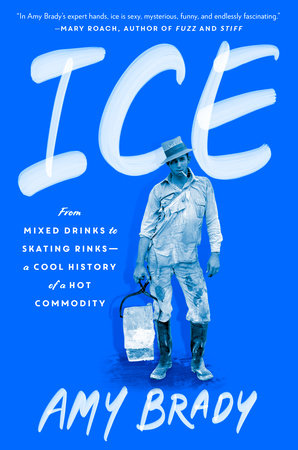

Chapter 1The Man Who Would Be Ice KingThe history of America's obsession with ice is much like the history of America itself: steeped in myth, given shape by acts of defiance, powered by commercial interests, and driven by bold yet deeply flawed men with visions that would change the world. It could be said to begin in Boston on September 4, 1783, just a day after the Revolutionary War ended, when Delia Jarvis Tudor gave birth to her third son, Frederic Tudor. No one could have known it then, but Frederic would one day spark a revolution of another kind: a revolution in how Americans think of and use ice.

The sun was shining the day I visited the site where Tudor's childhood home once stood. A couple of blocks over, I could see Boston's Old State House, where his father, a high-ranking judge named William Tudor Sr., would have hobnobbed with merchants and met senators for midday drinks. Not far to the north is the Bell in Hand Tavern, opened in 1795 and purportedly the nation's oldest bar, whose cocktails today, clinking with ice, are an unacknowledged tribute to Tudor's influence. In 1806, Tudor would have walked a half mile east from here to the harbor, where he'd set sail on the first American ship to carry blocks of ice on the open sea. Forty years later, he would stand in that same spot and, spitting curses, toss his wife's belongings into the water.

I went to Boston to better understand this man who was crowned the "Ice King" by the city's newspapers for his success in launching the American ice trade. He was a man, I would learn, of many contradictions: a fortune seeker who frequently spent more than he made; a charming salesman with a violent temper; a shortsighted businessman but also a visionary. Where his Bostonian peers were skeptical of a plan to make money off something as common and, well,

free as Massachusetts lake ice, Frederic wrote to potential investors asking for the capital to harvest what only he saw as a bounty to then sell in warm climates around the world. Almost everyone, except a few savvy financiers, thought he was mad for even suggesting the idea. No one had ever attempted to ship ice long distances. How would he keep it from melting? And who would buy it-and why?

Frederic, however, had a vision as well as a business plan. He also suffered a personal loss that haunted him for years, a loss that likely helped spur his desire to create a nation of people utterly obsessed with ice-and eager to pay for it.

***In February 1801, Frederic Tudor was just seventeen years old and had long been a thorn in his father’s side. William Sr. believed that success meant a respectable career in business or law, but Frederic had refused to go to college-not even to Harvard, where the judge’s business partners would have granted him admission. Instead, Frederic insisted on trying one moneymaking scheme after another, learning the ropes by experience-and mostly failure-rather than by the books. Exasperated, his father asked Frederic to join his brother, John Henry, who was suffering from bouts of weakness and a knee condition, on a months-long trip to Cuba. The trip, he figured, might force Frederic to stop his scheming and rethink his career path. Or so he hoped.

Frederic agreed-who would turn down an all-expense trip to the tropics?-and later that month, the brothers boarded a ship named

Patty in Boston Harbor. They carried suitcases full of wool suits-the fashion of the day, even in warm temperatures-and nearly two hundred boiled eggs. The family chef had told them eggs would travel well. They did not.

As the ship departed, the brothers' minds were likely filled with dreams of sun-drenched Havana, an image that would have been in stark contrast to the cold, gray harbor stretched out before them. This had been an especially stormy winter in New England, and the sky roiled with ominous clouds. The ship set sail anyway, and within hours, a downpour flooded the deck, forcing the men to their cabins. The incessant rocking of the ship soured their stomachs. They spent the next several days sitting on their cots, bent at their waists, heaving into bedpans.

The ocean grew calmer once they reached southern waters. The sun came out, burning their noses and zapping the seawater collecting on the deck, turning it to steam. The brothers were at a loss for how to cope with the heat. Some of the crew suggested they avoid the sun by staying in their cabins, but without good ventilation, the tiny rooms were intolerably hot. The trip lasted four weeks.

When the

Patty finally docked in Havana, the brothers death-marched onto shore with, as John Henry later wrote, "their tongues hanging out." Surrounding them were palm trees swaying in a light breeze. A cerulean blue ocean lapped at white sands. Paradise, it seemed, was everywhere they looked. Frederic hired an English-speaking servant named Francisco, who at first was something like a godsend: he introduced the men to pineapple juice and rum, fresh oranges, sweet guavas, and green figs. But when he noticed John Henry's poor health, Francisco (along with the woman who owned the house the brothers were staying in) restricted his diet to rice and water, an intervention that did nothing except annoy John Henry, who was determined to eat whatever he wanted, even if he had "to fight Francisco, kick the old woman & tell the doctor he's a quack." John Henry's knee grew worse.

Spring turned into summer, which brought even warmer weather, which in turn brought clouds of mosquitoes and armies of scorpions. The insect invasion was followed by a raging epidemic of yellow fever, a disease that ravaged the Caribbean and much of the American South every year. Doctors and scientists had yet to develop a vaccine for the disease, largely because they didn't understand that mosquitoes transmitted it through their stinging bites.

People throughout Havana fell ill with "the shakes"-a symptom of high fever that could last for days. When both Tudors caught this, they didn't know how to treat their aches and pains. Back home, they would have asked a servant to chisel chunks of ice from a block stored in the family icehouse so that they could press the cool substance to their hot foreheads. But warm places like Cuba didn't have icehouses, or even frozen water. The temperatures never dropped low enough, and a slap to the ocean's tepid surface would send a spray to the face that felt like sweat.

When other Americans left, so did the brothers. They purchased passage on a ship to Charleston, South Carolina, the first ship back to the United States they could get on short notice. Their luck didn't improve. The ship turned out to be carrying molasses in its cargo, which gave off a stench that oscillated between overripe fruit and rotting meat. Meanwhile, the heat was unbearable, and there was no way to get cool.

Eventually they made it to Philadelphia, where they parted ways. Frederic went back to Boston, and John Henry stayed behind. John Henry's health continued to fail, and in January 1802 he died with his mother by his bedside. His death shook Frederic to his core. For the next year, Frederic lived in alternating states of rage and regret. If only he had had access to ice in Cuba, he thought, perhaps his brother would have survived. Today we know that ice wouldn't have saved John Henry. He likely suffered from bone tuberculosis, a rare disease that requires specialized treatment developed only in the last one hundred years. But Frederic didn't know that. As far as he knew, John Henry died because he couldn't get cool.

Over the next several months, Frederic's behavior grew erratic. His family and friends avoided him, so he bought a diary to record his rants. Death and revenge on his mind, he drew a tombstone on the cover. Inside the drawing he wrote the following: "He who gives back at the first repulse and without striking the second blow, despairs of success, has never been, is not, and never will be, a hero in love, war or business." This vague threat aimed at no one in particular would become something of a motto for Frederic for the rest of his life.

***During the nineteenth century, most wealthy families living in cool climates like New England enjoyed ice year-round, thanks to icehouses. These “houses” were more like stone cellars built on private land that went several feet into the ground where temperatures, even in summer, rarely rose above fifty degrees. George Washington owned a sizable icehouse at Mount Vernon in Virginia, which his enslaved servants famously stocked to make a novel dessert called ice cream. In 1793, Martha Washington wrote that “in the warm season Ice is the most agreable [sic] thing we can have.”

Frederic Tudor knew the comforts of coolness. As one of the wealthiest families in Boston, the Tudors owned a large icehouse that their servants kept filled with blocks of ice year-round. Every winter, the Tudor servants risked their lives by cutting 100-pound blocks of ice out of Fresh Pond, a lake not far from the Tudors' country estate. They'd stand several yards out on the slick, frozen water, where the frigid wind blew hardest but the ice grew deepest. They carved the ice by hand using large saws, praying with every stroke that the frozen water held their weight. Once the ice broke free, the men used long metal rods to float the blocks as close to shore as possible. There, another half dozen men with horses waited to heave the blocks onto land and into the back of a wagon. Back at the icehouse, servants carried the blocks several feet to the bottom, where they stacked them vertically then padded them with sawdust and straw to keep them from melting. If packed tightly enough together to prevent airflow between them, the blocks would last the whole year.

The Tudor family used ice in many ways. Frederic liked to drop chunks of it into glasses of wine. The Tudor men preserved their freshly hunted game between blocks. When anyone fell ill or suffered an injury, servants nursed them back to health by pressing ice chips wrapped in cloth to their aching bodies.

These were likely the uses Frederic had in mind when, on a night in August 1805, he sat at his father's mahogany desk to sketch out the beginning of a grand plan. What if, he wondered, he could ship ice to warm climates? Ice was practically nonexistent there, ships could arrive within a few weeks, and who could say how much people would be willing to pay for coolness, comfort, and health?

But Frederic feared competitors. "Some enterprising Yankee," he wrote in his diary, might get wind of his idea and "be induced to attempt the thing" before he could try it himself. He needed to start with somewhere farther away, a place no one else would attempt to trade ice, a place such as Cuba, whose climate he believed was responsible for his brother's death.

He consulted a merchant friend of his father's on the legality of his plans. The friend explained that Frederic would have to secure permissions from the country's local governments before he could sell ice there, and Cuba made those permissions almost impossible to get. Disappointed, Frederic set his eyes instead on Martinique, a French-colonized island in the Caribbean. "Our plan now is... to sail by the first of November for Martinique," he wrote in his diary, "and at St. Pierre solicit the French government for this exclusive privilege." Initially, Frederic had every confidence that things would work out. "There can be very little doubt... they will be so pleased with the idea that the grant may be readily obtained," he wrote.

The scheme's greatest challenge, as far as Frederic was concerned, would be securing the capital to harvest enough ice to make the trip worthwhile. In the following weeks he asked every well-to-do connection he had for a loan, including Harrison Gray Otis, a former associate of his father's and by then a state senator. Frederic wrote the man a letter saying he had it on "good authority" that ice can be preserved on ships for long stretches of time at sea. (He actually had no evidence of this.) He referred to regular shipments of ice from Norway to London as proof that his plan would work. (There's nothing in the historical record to suggest that a Norwegian ice trade had yet been established.)

The senator refused, writing that the plan wasn't for him but still "sounds plausible." Frederic confined his annoyance to his diary, where he wrote, "Whether [the senator] did think it plausible or no, he is too much of a politician for

me to find out." In a letter to another potential investor, he dropped a line that would make Arnold Schwarzenegger's ice-pun-making villain Mr. Freeze from the 1997

Batman & Robin movie quite proud: "For heaven's sake, do not be too

cold to the thing and miss a passing opportunity." (Emphasis added.)

While he awaited response, another problem was beginning to dawn on him. Frederic couldn't be in Boston overseeing the ice harvesting and in the tropics getting trade permissions at the same time, so he turned to his older, twenty-six-year-old brother, William, for help. William, whose heavily lidded eyes were often shielded by a mop of unkempt hair, wasn't thrilled with the idea of going into business. He was a poet who eventually cofounded the

North American Review, not an entrepreneur. But once he learned that the job included luxury travel (or so he thought) to the tropics, he agreed to assist. For company on the voyage, William recruited their cousin James Savage. Frederic agreed to the choice because the cousin had "some business habits and character in him," welcome contrasts to what he saw as William's perpetual mooniness.

On a warmer-than-usual November day, Frederic, now twenty-two, stood on the dock of Boston Harbor and waved as his brother and cousin set sail on a ship called

Jane for Martinique. The decision to start their venture there may have seemed to make business sense, but it proved a dangerous choice. This was 1805, and a war had recently broken out between Britain and France. When the

Jane was more than halfway to Martinique, it came face-to-face with a British warship that insisted on inspecting what the vessel was carrying. This wasn't unusual. As a neutral nation during the Napoleonic Wars, the young republic engaged in trade with both warring countries-an agreement that had made many American traders of the era very rich. But this also meant that American ships were often subject to search-and on occasion, to questionably legal seizure. Eventually the British soldiers were satisfied with Jane's civilian status and let the crew go.

Jane sailed on.

The night they approached Martinique, the sea was tranquil. In an era before electricity, the Milky Way would have stretched above them in a twinkling ribbon of light. Then, suddenly, came cannon fire. The shot fell just short of the bow. A frantic crew member climbed the shrouds and hung a lantern to signal

Jane’s neutrality. The firing stopped, but everyone aboard agreed to drop anchor for the night just in case the conflict resumed. The next morning, with all still clear, the ship sailed into the port of St. Pierre.

***

In the late eighteenth century, as revolution shook France and its colonies, the French legislature formally abolished slavery. But this was no help for the enslaved of Martinique, as the British seized the island from the French in 1794, never allowing the abolition to take root. By the time William and James arrived in 1805, St. Pierre was home to more than thirty-thousand enslaved people and their owners—all of whom produced waste. The waste was carried by streams of gray water that gushed through the cobbled streets of town. A putrid smell filled the air from dawn to dusk, and the heat, even in November, somehow thickened it. Somewhere along the journey, both William and James contracted a virus—possibly yellow fever—that left them bedridden for days. When they were finally well enough to schedule meetings with local authority figures about trade permissions, no one would see them. They thought the idea to sell ice was too strange.

Still weak, the men half-walked, half-limped from office to office until, finally, a local prefect granted them the permission they sought, after accepting a bribe of two gold coins. The contract would allow the men to start selling ice immediately. Satisfied, they set sail again, this time for Jamaica.

This stretch of the trip went almost as poorly as the last. They were on a different ship, and this ship’s captain was deep in his cups by ten each morning, rarely leaving his cabin after the first drink. This left the duties of steering the ship to the first mate, who was largely unfamiliar with the ship’s mechanics and nearly capsized the vessel twice. Everyone agreed to dock in Santo Domingo to search for a new captain to lead them on. It was an unplanned stop, but since they were there anyway, William and James figured they’d apply for permission to sell ice. The local government granted their request, but that was the end of their good luck. French soldiers occupying the Dominican Republic prevented them from traveling to any other island. They managed to find passage on a Danish schooner bound for Jamaica, but a privateer stopped them just outside of Port Royal and took William’s ornate pistols. When they were finally permitted to proceed to port, they stayed for several weeks, just to avoid having to get back on a ship. "A seaman’s life is a dog’s life," James later wrote.

Copyright © 2023 by Amy Brady. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.