1

“World King”

To adapt tolstoy: all families are special, but big families are—simply by virtue or demerit of their size—more special than standard-issue families just because of this one thing.

There are more of you.

The infinite scope for conflict, friction, jollity, japes, scrapes, fights, and sheer visibility (on a clear day in the U.K. it feels as if you can see and hear the blond tribe of the Johnsons from space) is multiplied exponentially by the number of its members.

No surprise then that large, noisy, public families have a grip on the public imagination. The Mitfords (six daughters, one forgotten son, crazy Farve who hunted his own children to hounds, submissive Mother). The Kennedys. The royal family. The Waltons (as you can sense, I am already running out of famous clans quite quickly before I fasten on my own).

It is a trope that every country regards itself as exceptional, while every child thinks his or her childhood, however peculiar, is normal, because that is all they know.

That wasn’t the case in our family. I think we all knew, right from the beginning.

I definitely knew our family was . . . different. From about the age of three I would lie in bed as I heard the grown-up shouts of laughter over those raffia-covered pregnant bottles of cheap Chianti and breathed in their cigarette smoke, thinking, “Why am I part of this family and not another family? How did I end up HERE?”

My parents were in their very early twenties when they started reproducing. Looking back, I can’t help measuring my life—and even my adult children’s lives—against my parents’ own early milestones, even though I realise my mother and father were basically babies when they had babies and that fact alone explains a lot about how things turned out.

“My mother had three children by the time she was your age,” I said to my oldest son the other day and watched him wince. “When I got pregnant with you, the NHS considered me an elderly primigravida AND I WAS ONLY TWENTY-SIX.”

I’m not sure what the point of these comparisons is, but I was always aware that my parents were virtual prodigies because they married straight outta Oxford, had four kids, then divorced seventeen years later.

It was always just assumed that said kids would all go to Oxford and at least one of us—maybe more, my father went on to marry again and have two more children, so I am one of six, and there is no limit to his ambition for his offspring—would become, at the very least, the most important person in the country. (Years ago, people would start asking, “Did your brother always want to be prime minister?” I would answer, “No, he’s far more ambitious than that.”)

That was always the plan.

In 1970, when i was five, a family friend came to see us in Primrose Hill.

We lived in two houses in Primrose Hill. The first Johnson residence in NW1 was in Princess Road, bang next to our school, Primrose Hill Primary.

The house was a new-build brick box my mother found easy to clean, or at least easier to clean than our next house in NW1, a crumbling, Victorian, semidetached, stucco-fronted affair opposite the shops on Regent’s Park Road, where we moved shortly after my mother had a fourth baby, Joseph, and shortly before my father shunted the whole family to Brussels in 1973 (and then sold Regent’s Park Road over the phone to the journalist Simon Jenkins, who’d called to say his current girlfriend, Gayle—a high-maintenance Texas actress who went on to transform my tiny bedroom in the extension into a California-style storage “solution” just for her shoes—wouldn’t marry him unless he got our house. My father agreed, as he has never to my knowledge said no to anything. “What was a chap to do?” my father explained. “Simon was, you know, very keen on Gayle at the time.”).

We weren’t in either Primrose Hill or Regent’s Park Road long. I remember the latter mainly for the times we left home to go to Casualty.

One day Jo, nine months, consumed some succulent fungus he’d found after crawling behind the washing machine in the basement. His eyes rolled back, he went a funny colour, and my mother had to rush him to University College Hospital, where, as chance would have it, I was already an inpatient, having inhaled eggshell after Al made me choke with laughter over breakfast while I was in the middle of my boiled egg. This resulted in a collapsed lung and pneumonia. I was in hospital so long I did morning lessons on the children’s ward and received my own post. All my little classmates were ordered to write me cards. (Maureen wrote, “At School we have been making animals out of flet [sic] and I hope you better,” and my best friend, Stephen Devaney, wrote, “I’m missing you alot. Specially because of the egg shell in your lung.”)

Being in hospital remains one of my happiest childhood memories (my mother, now seventy-seven, gave me the get-well cards but still has the eggshell in a jar that she keeps in a special place along with locks of baby hair and teeth, all to be dealt with in the fullness of time).

“Your baby appears to be high, Mrs. Johnson,” the Accident and Emergency doctor said, noting her return without surprise, and took Jo away to have his stomach pumped. (I know how bad this sounds, but don’t forget it was the 1970s. As someone commented at length below the line after a piece I wrote for The Telegraph about how much I relished my time at prep school—where it was mainly beating, early-morning Greek, and predatory schoolmasters—today the Johnson children would be taken into care.)

Anyway, when this family friend paid his visit, Al would have been around six years old. He was born fifteen months before me yet I get furious if people don’t know this as I have poured so much time and money into mad, expensive “age-reversal” creams and a punishing fitness and diet schedule, and he very much has not.

In this first memory we were in the downstairs playroom, with its smart modern floor of cork tiles and modular furniture covered with polyester-clad thin foam cushions.

We didn’t have a garden, but went to Primrose Hill or used the car park reserved for the other residents of the development, affixed with large signs saying “No Ball Games” and “No Dogs” where we used to play noisy games and thud balls percussively against our neighbours’ garage doors. Once, when a man told us to stop, we told on him and my father came out and shouted that if the neighbour told us off again he would “knock his block off”—an act of muscular fatherhood we still remember with admiration and affection to this day.

Down in the playroom, I was in a navy hand-knitted jersey and navy cords and Al was in an identical outfit, only in brown. He might have been sitting in a cardboard box as we were in the middle of a game. We all used to beg him to play games as he made them such fun, but from about the age of ten he would answer, “Okay, let’s play reading,” which was crushing. Or he would go to his room to stage ancient naval battles in his sink, using corks, pins, and card to re-create the Greek and Persian fleets at, say, Salamis in 480 b.c. (I am genuinely not making this up).

We had no television and never had friends over. Other mothers considered our family “too rough,” and as my brother’s future wife, Marina, whom we have known since the age of six, confirmed to a biographer years later, we were also “wild and out of control,” our “house was always freezing,” and furthermore “we all had holes in our socks.”

Marina’s mother, Dip, stopped her from coming round after my younger brother Leo, aged six, shot Al in the stomach with an air rifle, another red-letter day in the Johnson household. When Al—I guess around nine—was carted to hospital, doctors discovered the pellets had pinged off his dense layer of puppy fat. “I wanted to try and miss Al by a tiny margin to prove I had power of life and death over him,” Leo explained when asked why he had shot his brother, “but got him in the middle of the stomach instead.” Leo maintains he would do the same today.

In fact, beyond Marina we never really had friends, as we were always moving house or country. As a result we all ended up reading so much that my mother used to shout up to our rooms, “Children! What are you doing?”

“Reading,” we would all answer in turn.

“Well, stop reading!” she would shriek.

Back to Tony, the friend of my parents, who was in a suit in the downstairs playroom.

He knelt to our level and laid his hands on both our blond heads.

“So, children,” he said. “Tell me. What do you want to be when you grow up, Rachel and Alexander?” As we gazed up at him from under our thick yellow pudding bowls, cut by our mother with kitchen scissors with towels round our shoulders, we pondered this question.

I tried to think of what women did when they grew up.

My mother was—is—a painter, and a very remarkable one, but I didn’t see her like that then. It seemed to me she spent most of her time when she wasn’t looking after us smoking or on the telephone or cleaning (a few years later she was admitted to the Maudsley Hospital and stayed there for many long months with a case of OCD so severe that doctors ended up trying, and failing, to cure her with electric shock treatment, which was at least less violent than the other therapy most fashionable at the time: a lobotomy).

I had lots of aunts and uncles: on the maternal Fawcett side, my mother’s older sister Sarah was a nun (“Auntie Nun”). Her younger brother, my groovy black-polo-necked uncle Edmund, worked for Rolling Stone (“Uncle Monkey”). My mother’s two younger sisters were too young to have jobs. My father’s three siblings? Hilary was married with children. Peter worked in town planning. Birdie was too young to do anything.

My Fawcett grandmother, a former ballerina, didn’t work or eat but was a marvellous cook, and I can taste the crunchy pastry of her buttery Bakewell tart to this day. Granny Butter, my father’s mother, was a hill farmer’s wife on Exmoor.

It was the first time I had considered the future riddle of grown-up existence. Still, I had just learned to read. My mother taught me with the Ladybird books. The Little Red Hen, The Hovercraft, and Red Riding Hood are all etched on my memory but none more so than the definitive “Peter and Jane” series published in 1964, foregrounding a tidy, traditional nuclear family in a tidy, traditional suburb of Middle England to prepare the children of Britain for what lay ahead.

Here is Peter and here is Jane. Here is Pat, the dog.

The series starts off reasonably gender-neutral and equal opportunities (the Equal Pay Act was not until 1970), but it all goes Gilead meets Good Housekeeping without passing Go by page 6.

Jane is in the kitchen with her mother in a white frock and yellow cardigan, like a mini Princess Lilibet.

Jane likes to help Mummy. She wants to make cakes like Mummy.

“Let me help you, Mummy,” she says. “Will you let me help, please? I can make cakes like you.”

“Yes,” says Mummy. “I will let you help me. You are a good girl.”

Meanwhile, Peter was romping with Pat the dog in a Red Indian costume with a feathered headdress, and Daddy was washing the car with a hose.

“We will make some cakes for Peter and Daddy,” says Jane. “They like the cakes we make.”

I answered first. I had read Peter and Jane. I had done my homework like a girly swot. The future was clear as a windowpane.

“I want to be a wife and mother,” I answered. I felt that covered all the available bases.

I remember my father’s face. What was wrong with being a wife and mother, like his wife and my mother? I wondered.

His long trips as a white saviour among distant tribes in the Amazon, or exploring in Africa (he called the first volume of his autobiography Stanley, I Presume?), or researching his many books about the green revolution or population control in India or China—his contact with his family limited to sending postcards home from Kinshasa or Burundi every so often—had left my prodigiously talented mother no option. She was a tethered brood mare, even though all she wanted to do was paint in her studio that children were never allowed to enter unless she was painting them.

“Alexander?” Tony (Anthony Howard, the editor of the New Statesman—I’m pretty sure it was he as there is a picture of this touching tableau in some family album) now turned to my brother.

“World King,” he announced confidently, as if he already felt the hand of destiny heavy on his small shoulders. My father nodded with grim satisfaction.

I admit, that shook me. I saw him in a cold, new light. I saw life in a cold, new light. Was that even a job? Could girls apply? I pondered these things in my heart.

That short exchange, folks, was possibly the formative conversation of my childhood.

And his.

That was, in part, how we ended up here.

I did not feel the “hand of destiny” as a small child. Maybe I was the wrong sex, and it was a confidence thing, like all men secretly knowing they can get a point off Serena Williams at tennis, while all women knowing they can’t, and all Etonians thinking they can be prime minister.

I can’t blame my parents for that. In fact, I am long past the point of blaming them for anything, and never have. As soon as you become a parent yourself, you realise that your mother and father did their level best under impossible circumstances.

In fact, I had it much easier than my brothers. I was the only girl. And I was only a girl. It was my get out of jail free. Nobody expected or wanted me to be World King. Imagine the relief!

But this is not a memoir (please, I am not so delusional as to think I am an Elton John or a Michelle Obama; any memoir will have to wait until I’m at least seventy), more a lightish, three-course meal.

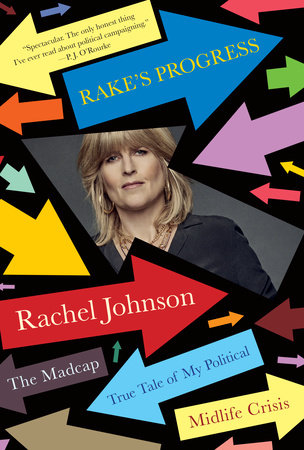

The “mains” in the middle is my abject, absurd, but not entirely ignoble failure to be elected to public office for a new, centre-ground, pro-EU political party just as my own brother made his own successful one-man moon shot on Downing Street in July 2019.

Copyright © 2021 by Rachel Johnson. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.