Chapter 1

Protecting the Poor

In the spring of 1968, Sylvester Smith, of Selma, Alabama, asked the Supreme Court to restore her welfare benefits. The thirty-four-year-old Smith, a widow with four young children, worked from 3:30 a.m. until noon as a waitress and cook and picked cotton in her time off, but she earned only about $20 a week. She supplemented her wages with about $29 a month in Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), a federal cash assistance program for low-income families with children, jointly administered by the federal and state governments. When a tough new caseworker named Jacquelyn Stancil took over her case, Smith was told that she and her children were no longer eligible for benefits, because of information the state had received from an anonymous source. The problem, Stancil said, using the terminology of the day, was that there was a "man in the house."

Alabama was one of eighteen states with a "man in the house" rule, which denied welfare benefits to mothers who were having sex with a man on a regular basis. In Alabama, a man who visited frequently "for the purpose of cohabiting with" the mother, or met with her elsewhere for sex, was deemed a "substitute father" and obligated to support the family. The rule was meant to save the government money, but it also reflected the view that, as The New York Times put it, welfare was "an inducement to immoral behavior, especially among Negroes." Alabama's top welfare official defended the man-in-the-house rule by saying that a mother who lost her benefits could always choose "to give up her pleasure" and "act like a woman ought to" to get them back.

Stancil had received a tip that Smith had a boyfriend who visited her home-a shack on the outskirts of Selma-on weekends. Smith did have a boyfriend, a married man named William E. Williams, but, like many of the men who visited welfare mothers, he had little money, and he had a wife and nine children of his own. Williams gave Smith $4 or $5 a month, but he could not support her family, which Smith understood. "Ain't much he can do," she said. "You can't make a man take care of his own kids, much less take care of other people's kids."

Stancil told Smith that if she did not break off with Williams, she and her children would lose their AFDC benefits. Under Alabama law, Smith could defend against the charge that she had a boyfriend by providing evidence that she did not, including references from people considered to be in a position to know, such as clergymen, neighbors, or grocers. Welfare officials would ask the references if they believed she was having sexual relations. Smith, however, did not deny that she was seeing Williams. "If I end with him, I'm gonna make a relationship with somebody," she said. "If God had intended for me to be a nun, I'd be a nun."

Smith's situation was not unusual. Alabama adopted the man-in-the-house rule in 1964, and 15,000 children were removed from the AFDC rolls under it in the first year. Another 6,400 poor children were turned down when their mothers applied for AFDC. An analysis of the cases closed in Alabama because of the man-in-the-house rule found that 97 percent of the children were black. Nationwide, the numbers were far larger: it was estimated that more than 500,000 children were being denied benefits because of state man-in-the-house rules.

What was unusual about Smith's case was that she fought back. She challenged Alabama's rule in federal court. It was a courageous act for a poor African American widow and mother of four to take in 1960s Alabama, and it came at considerable personal cost. While the lawsuit proceeded, Smith's benefits were cut off, and the Selma power structure closed ranks against her. Stores refused to extend her credit to buy groceries, and at times her children went hungry. Smith also lost the minimal support she received from Williams, who stopped his visits after she filed suit.

Welfare recipients had many burdensome conditions imposed on them in the 1960s, but few were as despised as the man-in-the-house rule. It was widely understood that welfare officials saw it as a tool for removing people from the rolls, particularly black women and children. The man-in-the-house rule was, one analysis of Smith's case noted, the preferred tool for "an Alabama welfare official intent upon lopping off a lot of black bodies in a hurry." The rule also let caseworkers probe the most intimate aspects of their clients' lives. Two years earlier, the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund had declared at a Washington, D.C., press conference that ending the man-in-the-house rule was one of its top priorities. The rule put the welfare mother in an "impossible dilemma," the group said, forcing her to choose between conducting "a secret relationship" while living "as if she were a criminal" or abandoning "her efforts to develop male friendships altogether."

Smith's case was taken up by northern lawyers, including ones from Columbia University's Center on Social Welfare Policy and Law. These lawyers thought Smith's challenge would be a strong national test case. Since Williams did not live in the home, was not the father of any of the children, and was too poor to support them, the state's claim that he should be considered a "substitute father" was weak. Alabama was also a good state to bring a challenge in. Governor George Wallace had stood in the schoolhouse door to resist integration at the University of Alabama just a few years earlier, and the state's close association with virulent racism meant there would be little sympathy for it if the case reached the Supreme Court.

Smith's lawyers argued that the man-in-the-house rule violated her rights under two parts of the Fourteenth Amendment: the Equal Protection Clause, which says the government cannot deny people "equal protection of the laws," and the Due Process Clause, which prohibits the government from denying life, liberty, or property without "due process of law." The lawyers also argued more narrowly that the rule violated the federal AFDC statute, because it denied welfare benefits to children who were entitled to them under the law. The statute required states that participated in the program to provide benefits to needy children if their father was dead, absent, or incapacitated, which Alabama was not doing for Smith's children.

The Supreme Court accepted the case, and it heard oral arguments on April 23, 1968, just weeks after Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. It was clear from the justices' questions that the man-in-the-house rule was in trouble. Warren expressed concern over whether welfare families like Smith's actually received support from the purported "substitute fathers" covered by the rule. Marshall, the first black justice, who earlier in his career had been director-counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, and William O. Douglas, the Court's most liberal member, questioned why the Smith children should be penalized for actions they had nothing to do with.

On June 17, 1968, in King v. Smith, the Court ruled for Smith by a 9-0 vote. It took a narrow approach, holding that the man-in-the-house rule violated the AFDC statute, and not reaching the larger equal protection and due process issues. Warren, who wrote the Court's opinion, said that under the statute, benefits had to be provided to every eligible "dependent child" deprived of "parental" support." Alabama's rule was invalid, Warren said, because poor children without fathers cannot be denied aid "on the transparent fiction that they have a substitute father."

The Court's narrow approach to the case was not surprising. Courts generally try to decide cases based on statutes rather than the Constitution whenever they can, a principle that is known as "constitutional avoidance." By ruling under the AFDC statute, the Court did not create any broad new constitutional rights for poor people that they could apply in other kinds of cases. Still, the decision's real-world impact was undeniably large. In addition to restoring the Smith family's benefits, it prevented about 500,000 children nationwide from losing benefits because of an irrational and cruel governmental dictate. The language Warren used in his opinion also highlighted the challenges faced by poor families like the Smiths. "All responsible government agencies in the Nation today," he declared, "recognize the enormity and pervasiveness of social ills caused by poverty."

Smith was pleased by the Court's ruling, and by the fact that it would help other AFDC recipients. "A lot of the ladies who got aid because of my case thank me," she said later. Legal commentators overwhelmingly praised the Court for striking down an invasive and mean-spirited rule and hoped the decision would be the first of many more like it. "The King decision is a salutary one," an article in the North Carolina Law Review declared, and it "very likely signifies a new role for the Supreme Court in protecting the rights of welfare recipients, though it is of small significance compared with the work yet to be done."

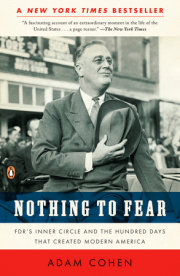

King v. Smith was the culmination of a decades-long drive to establish greater legal rights for the poor. The origins of this campaign lay in the Great Depression, when the Court began to express a new concern for the disadvantaged. Starting in 1933, Franklin RooseveltÕs New Dealers poured into Washington, D.C., on a mission to rescue the millions of Americans who had been driven into poverty, and some of that idealism eventually reached the Court. In 1938, in the obscure commercial case United States v. Carolene Products, the New Deal-inspired Court unveiled a new conception of the Equal Protection Clause that would systematically give special protection to the most vulnerable groups in society.

The Court set out its new vision for equal protection in footnote 4 of the Carolene Products decision, which has been called the most famous footnote in American law. The Court said that when it reviewed most laws, it would be highly deferential and rarely declare them unconstitutional. If a law imposed a special burden on "discrete and insular minorities," including religious, national, or racial minorities, however, the Court suggested it would apply a "more searching judicial inquiry." The Court's message was that it was highly likely that it would strike down laws that imposed special burdens on one of these vulnerable minority groups.

Footnote 4 marked a major new path for American constitutional law. To a degree it never had before, the Court was making a commitment to protect minorities who were too politically weak to protect themselves. It was not clear, however, which groups it considered to be "discrete and insular minorities" deserving of special protection. Footnote 4 expressly mentioned racial, religious, and national minorities, but it suggested that more groups might follow. One factor it said it would take into account was whether a group experienced prejudice that interfered with its ability to use "political processes ordinarily to be relied upon to protect minorities."

The Court did not raise the possibility that poor people would be one of these new protected classes, but there was a strong argument that they should be, based on the criteria in footnote 4. Poor people were a numerical minority. They were also a discrete and insular group: they were often physically segregated, in urban ghettos or on the "wrong" side of the tracks, and they were set apart socially by the stigma that attached to them in a nation that worshipped material success. Throughout American history, the poor had been a much reviled group, regarded as lazy, immoral, disease-carrying, and cursed by God. Poor people had also been unable to protect their rights through the political process. There had been a wide array of laws discriminating against them, including ones that consigned them to indentured servitude or poorhouses, and they had not been able to persuade the government to adopt welfare programs that would lift them out of poverty.

There was another factor working in favor of designating the poor a discrete and insular minority in the late 1930s. With so many formerly wealthy and middle-class Americans experiencing dramatic reversals of fortune during the Great Depression, there was a growing belief that poor people were not to blame for their misfortune. This new attitude came directly from the top. Roosevelt had declared at his inauguration on March 4, 1933, that poverty was a national problem that the government had an obligation to address. Later in his presidency, in his famous "Four Freedoms" speech, one of the freedoms Roosevelt argued for was "freedom from want."

There were also reasons, however, that the Court might be reluctant to designate the poor as a suspect class. Unlike racial and religious minorities, poor people were not yet recognized as a cohesive group that should be regarded as having collective rights. It also was not entirely clear what kinds of laws the Court would subject to heightened scrutiny if it decided that the poor were a suspect class. After all, even many of the most mundane government policies, like highway tolls and national park entrance fees, imposed a greater burden on the poor than the rich.

In 1941, in Edwards v. California, the Court had a chance to weigh in on the rights of the poor, and to use footnote 4 if it wanted to. The case was a challenge to a California law that made it a crime to transport a poor person into the state. Twenty-eight states had laws of this kind, which were known as anti-Okie laws, after the Oklahoma migrants immortalized in John Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath, who were the sort of people they were intended to keep out. The plaintiff in the case, Fred Edwards, had driven to Texas to pick up his brother-in-law, Frank Duncan, and Duncan's pregnant wife. He brought them back to his home, near Sacramento, and three weeks later Duncan's wife gave birth. Edwards was convicted of violating California's Welfare and Institutions Code, which barred "bringing into the state any indigent person who is not a resident of the state," and he was sentenced to six months in jail.

The Court struck down the law by a unanimous vote, though the justices disagreed on their legal rationales. The majority held that California's law violated the Commerce Clause, which limits the ability of states to interfere with exchanges between the states that have an economic impact, including the movement of people. Edwards was an important victory for the poor, since anti-Okie laws were so widespread and so stigmatizing. The majority opinion in Edwards also changed how the Court talked about poor people. Instead of calling them "paupers," "vagabonds," or a "moral pestilence," as it repeatedly had in past decisions, the Court went out of its way to humanize them. It was not true that "because a person is without employment and without funds, he constitutes a 'moral pestilence,'" the Court said. "Poverty and immorality are not synonymous."

Copyright © 2020 by Adam Cohen. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.