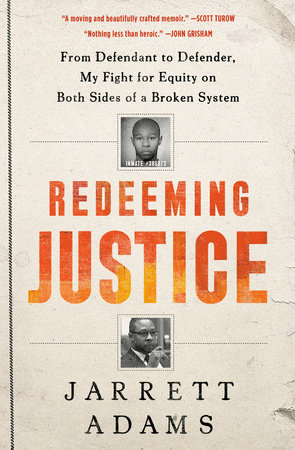

Life After Justice

November 2018

I walk through the woods with Kerri O’Brien, a local television news reporter who for the past three years has been covering the case involving my clients. I wear a dark suit and hold a leather binder. I squat and twigs snap under my dress shoes. I rub my palm on the ground and think about the men I’m representing.

On April 25, 1998, Allen Gibson, a white police officer in a small Virginia town, entered these woods behind an apartment complex and surprised Terence Richardson, twenty-eight, and Ferrone Claiborne, twenty-three, in the middle of a drug deal. The officer drew his gun, the two young men wrestled with him, and the gun went off, shooting Gibson in the stomach. Terence and Ferrone fled the scene. Shortly after, a state trooper discovered Gibson on the ground, bleeding, severely wounded. In his weakened condition, the officer managed to describe the drug deal and his attackers: two Black men, one with a ponytail, the other with dreadlocks. Later that afternoon, Gibson died in the hospital. On a tip from a witness, police picked up Terence and Ferrone and charged them with the murder of Allen Gibson. Open and shut. End of story.

Except not one word I just told you is true.

Terence and Ferrone were nowhere near these woods at the time of Gibson’s shooting. Police picked them up in separate locations, on opposite sides of town. Neither had a criminal record; neither had ever sold drugs. Investigators found no trace of their fingerprints, hair, or DNA at the crime scene, and neither wore a ponytail or dreads. Which should have raised a question: In the course of approximately thirty minutes, how could they have murdered a police officer, removed all the evidence, fled the scene, gotten rid of the drugs, changed, disposed of their clothes, gone to separate locations, and cut their hair?

Police rounded up and interrogated nearly every young Black male in Waverly, Virginia, determined to find two men to charge for the killing of the officer. They had a crime. They needed two criminals. It is still unclear how my clients’ names came up, but two days later police arrested them for the murder of the police officer. Fearing the death penalty and strongly encouraged by their lawyers, Terence and Ferrone pleaded guilty to lesser charges, Terence to involuntary manslaughter, Ferrone to accessory after the fact to involuntary manslaughter, a misdemeanor.

Despite being innocent, Terence and Ferrone made this choice because it was the only one offered them. Across America, in cities and in small towns—and especially in this small town—they saw that the police didn’t dispense equal justice to Blacks and whites. They had seen Black people routinely railroaded, sent to prison, put to death for nothing. When the same system came for them, Terence and Ferrone pleaded guilty to lesser charges to save their lives.

For members of the town’s white establishment, it wasn’t enough. They saw the punishment as a slap on the wrist. They wanted more. They wanted Terence and Ferrone’s heads.

Because Gibson’s shooting was linked to a drug deal, the FBI came in. The feds interviewed a parade of informants, making deals with several people in exchange for their testimony. A false portrait emerged of Terence and Ferrone as drug kingpins, even though neither had any history of drug dealing and police never found drugs in their possession or records of any large transactions or cash deposits.

In 2001, a jury in federal court additionally found Terence Richardson and Ferrone Claiborne guilty of conspiracy to sell crack cocaine. In a rare legal action, the judge used their previous murder charge and guilty pleas as a cross-reference to enhance their drug sentence. The judge sentenced them to life in prison.

Twenty years later, Terence and Ferrone sit in federal prison for a crime they didn’t commit.

I know what my clients are going through. I know they sometimes scream at the top of their lungs until their voices give out and then they continue to scream silently. I know they feel as if the walls were closing in on them. I know how with each day that passes they become diminished, feeling another piece of their humanity peeling off, like dead skin. I know exactly how they feel.

In 1998, I was falsely accused and ultimately wrongly convicted of rape. I was sentenced to prison for twenty-eight years. I, too, had done nothing. I, too, got terrible legal advice.

Unlike my clients, I made a catastrophic mistake that set the whole thing in motion, putting me on the path I’m on today.

I went to a party.

Three of us—three Black kids from Chicago—drove to a college campus in Wisconsin. At the party, we each had a consensual sexual encounter with the same girl, a white girl. Her roommate walked in, called her a slut, and stormed out. These were the facts. But the girl later said we raped her.

As a man raised by four strong, prideful women—my mom, grandmother, and aunts—I still have no idea or sense of how difficult it is for any woman to come forward after she has been raped. I cannot imagine the humiliation, shame, anger, and fear a woman must feel having to relive the details of her attack as she files a police report and submits to a rape kit test. As a lawyer, I know the statistics for false rape accusations. According to the National Sexual Violence Resource Center, only 2–10 percent of women falsely claim they have been raped.

My accuser falls into that 2–10 percent.

The police believed her. They charged us with rape, and we went to trial. I thought that if I told the truth, I would be safe. I trusted in the truth and in fairness. I believed in justice. After all, that’s what trials are about—justice, right?

Not necessarily. Particularly if the accused is poor, uneducated, and a person of color. In too many cases, justice doesn’t prevail, even if the accused is innocent. Some days, justice doesn’t even make an appearance.

At my trial, the prosecution’s insistence on getting a conviction at any cost and deep-rooted prejudice barred justice from the courtroom. Justice never had a chance. I never had a chance. The prosecutor looked at me and at Dimitri Henley and Rovaughn Hill—the friends on trial with me—and called us “three Black men from Chicago.” We had no names, but the all-white jury knew us. They’d seen “us” on the news. They’d read about “us” in the newspapers. We were criminals, drug dealers, gangbangers, rapists, killers. We were them. Three nameless Black men from Chicago. It didn’t matter that the prosecution presented no real evidence, that the so-called victim’s story made no sense. The truth didn’t matter. Like my clients Terence Richardson and Ferrone Claiborne and so many young Black men, I was convicted.

After nearly ten years, with the help of the Wisconsin Innocence Project (WIP), I was exonerated and released from prison. The court dropped all charges against me, and my record was expunged. I was free. Well, not quite. Ten years behind bars took its toll. I needed to adjust to the world outside. I found that reentering society was almost as difficult as surviving prison. A mash-up of emotions assaulted me—anger, despair, frustration, confusion. Eventually, thanks to the kindness of my mother, my family, co-workers, teachers, the commitment and hard work I put into therapy, and my faith, I emerged from a place of darkness and came to a place of healing. I also confirmed my path in life. In prison, I became a jailhouse lawyer, helping inmates with their legal issues. I made a vow to myself that once I got out, I would go to college and law school and become an actual, card-carrying attorney.

After my release, I began working on that promise. I felt as if I were on a mission and that God had answered my prayers. He gave me a second chance. Now I live to exceed His expectations. I work and live at warp speed.

“What drives you?” people ask.

Two emotions fuel me every day, motivating me to wake up at dawn and keep charging until I collapse from exhaustion late at night.

First, fear. Fear drives me. I’m afraid of not doing the right thing, of wasting time, of disappointing others, and of disappointing myself.

Second, commitment. I have made a commitment to serve those behind bars who have been locked up for minor crimes, serving unconscionably long sentences, and those who have been wrongly accused, people like Terence and Ferrone. I am fighting to set them free. The process takes perseverance, patience, and time—literally years, and sometimes even decades.

One day, as I was explaining a legal procedure to Ferrone, he suddenly blurted, “Had I known that by pleading guilty to save my life, it would’ve cost me my life . . .”

His voice, laced with pain, trailed off. But those three words seared into me.

Copyright © 2021 by Jarrett Adams. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.