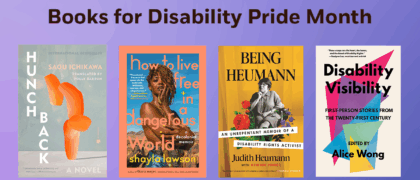

Books for Disability Pride Month

We are celebrating Disability Pride Month in July with books from disabled writers, artists, and activists who have fought to create a more inclusive world. Find our full collection of titles, which includes literature, memoir, and history here.