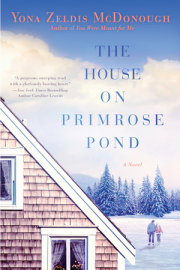

ONE

The supposedly hip place in Midtown was exactly the sort of place Miranda Berenzweig hated: cavernous, dim, and ear-splittingly loud. On one side of the room was a long, sleek bar made of highly polished black marble; on the other, a massive wall of water that rose from the floor like a tsunami. But since Bea was not only a hostess here but also dating the owner, their girl group had been lured by the promise of free food and drink. And look, here was Bea coming toward her.

“Hey,” she said and kissed Miranda on each cheek. “You’re the last one to arrive; everyone else is already ensconced. Follow me.” Miranda was happy to do exactly that; she needed a guide in this latter-day Hades. The percussive beat from the music reverberated in the cavity of her chest and the crush of bodies thwarted her at every turn. But Bea seemed unfazed. Up a flight of black marble steps whose wrought-iron railing pulsated with clusters of tiny white lights and down a short hall to a dark paneled door, which Bea pulled open with a flourish. “The VIP lounge,” she said. “Welcome!”

“We were getting worried about you,” Courtney said. She was five-eleven, and her sleek blond head towered above everyone else’s at the table.

“I was stuck at the office,” Miranda said, shrugging off her coat and sliding into the tufted velvet banquette. “You didn’t start without me, did you?”

“Of course not,” said Lauren, who looked at Bea. “You’ll be able to join us too? Even though you’re working?”

“My shift is just about to end,” Bea said.

Miranda had known Bea, along with Courtney and Lauren, since they had been freshmen at Bennington, and they still met every month or so to catch up on one another’s lives. Tonight Miranda had a piece of good news to share—her first in a while—and when Bea sat down, a tray of pale green appletinis following in her wake, she dove right in.

“You’re looking at the new online food editor of Domestic Goddess,” she announced. “We’re revamping the Web site and I’ll be responsible for all the food-related content.”

“Does this mean you won’t be handling the print edition anymore?” asked Lauren.

“No. The new job is in addition to, not instead of. So it’s a bump up.” Miranda took a sip of her drink—it was perfectly rendered—and smiled.

“Does it come with a raise?” Trust Courtney to bring up the subject of money.

“It most certainly does.” Miranda took a celebratory sip. Ooh, it was good. “A generous one.”

“Well, it’s high time,” said Courtney, who didn’t so much sip as gulp from her glass. “You can finally stop living like a church mouse. Maybe you’ll even move to Manhattan. You’re not doing yourself any good out in the hinterlands.”

Miranda went still. That was not a very tactful—or accurate—thing to say. She was not poor; she was frugal, which was an entirely different thing. She was diligent about putting money away for the proverbial rainy day, a concept Courtney, with her penchant for Chanel and Christian Louboutin, did not understand. Of course, Courtney was the accessories editor at Soigné magazine; she would claim her indulgences were necessities. “I love Brooklyn,” she said.

“And you have such a great apartment, right near the park and all,” Bea, ever loyal, added.

“It is a nice apartment,” Courtney conceded. “But it’s just so far from everything.”

“Not the things that matter to me,” Miranda said quietly. But the conversation was already moving on, and everyone was congratulating Bea, who’d announced that she was now one of two finalists vying for the part of Maggie in an out-of-town production ofCat on a Hot Tin Roof. Then Lauren told everyone how her youngest child, Max, had just been admitted to a highly regarded pre-K and they all toasted that with another round. Along with the drinks, platters of grilled shrimp, empanadas, and spicy, translucent noodles arrived.

“Here’s to finger painting!” sang out Bea.

Then it was Courtney’s turn. Miranda was seized with the small, petty hope that Courtney’s news did not involve her job; Courtney definitely had the more high-profile position—everyone knew Soigné—and she did not want her own promotion to be upstaged. There had always been a little thread of competition woven into her friendship with Courtney, something not present in her feelings for Bea or Lauren. But Courtney could also be her biggest booster, and it had been through a connection of Courtney’s that Miranda had landed atDomestic Goddess.

“Harris proposed!” Courtney sang out. “We’re getting married!”

“That’s wonderful!” Lauren and Bea started to clap.

“Mazel tov.” Miranda tried to sound genuine though she thought Harris, a pedantic lawyer with a receding hairline and a premature paunch, was hardly a prize.

“Now you’re the only one who’s unattached,” said Courtney to Miranda. “Girls, we have to find someone for Miranda. She’s too special to remain on the vine. Maybe Harris has a friend. I’m going to ask.”

Miranda, stung, said nothing. So what if she was single midway into her thirties? Was that a deficiency? A crime? “No Ivy League lawyers for me,” she said, striving to keep her tone light. Harris had gone to Harvard, a fact he managed to work into all conversations, even ones that were ostensibly about the weather.

“What’s wrong with lawyers?” Courtney said. They had moved on to White Russians—sprinkled with pulverized chocolate and dusted with nutmeg—which Bea said were the bar’s signature libation. “Harris says that the law is the most stimulating intellectual pursuit he can imagine.”

Then his imagination must be pretty small, thought Miranda.

“And that the people he met at Harvard—”

“I didn’t say there was anything wrong with lawyers,” Miranda interrupted. Now he has her doing it too! “I’m just looking for someone with, oh, I don’t know, a more artistic bent.”

“You mean some out-of-work painter who’ll sponge off you for months before he maxes out your credit cards and moves on to a twenty-five-year-old?” said Courtney.

“That,” said Bea in a gentle but reproving tone, “isn’t necessary. Or nice.”

Miranda pushed her glass away. Ordinarily she loved White Russians, but suddenly the sweetness was nauseating; she thought she might be sick. Did Courtney need to dredge all that up now? And anyway, she was exaggerating. When Luke had gotten fired from his carpentry job, Miranda had offered to stake his purchase of art supplies so that he could keep on painting. But he was still morose and moody and she’d encouraged him to treat himself: expensive lunches, a new Italian suit from Barneys. But he’d hardly maxed out her card. Anyway, she had paid off the sizable AmEx bill, and her heart, though still bruised, was nonetheless on the pitted and rubble-strewn road to recovery.

“God, you’re treating Miranda like she’s made of glass or something.” Courtney put a hand on Miranda’s arm. “You know that I’m just concerned about you. We all are.”

“Not necessary. I’m fine.” Miranda stood up and brushed at her dark skirt, as if to wipe the lie away. Thanks to Bea’s largesse, she was past her limit, and she swayed slightly on her feet. Better go home before she said something she’d regret.

Her standing up seemed to give the cue to Lauren and Courtney; the three women jostled their way through the still-crowded front room and out into the raw March night. Lauren and Courtney both lived uptown, and they headed off in the other direction. Bea and her manager boyfriend were still at the bar, which did not close until four a.m.

Miranda was alone. It was late, she was exhausted, and it had started to rain. To hell with being frugal; she was taking a taxi home. Raising her arm, she stepped off the curb to hail one.

But it seemed there was not a single available cab to be had in the entire city. After twenty minutes of watching taxi after taxi whoosh down the slick streets, she gave up and trudged toward the subway station on Forty-second Street. The platform was as full as if it had been the morning rush. Two musicians—a drummer and a guitarist—were at either end; the drummer, beating on several inverted plastic containers, was particularly good. A gaggle of teenage girls preened for the boys nearby. A large Hispanic family occupied an entire bench, and a couple leaning against a metal support kissed languorously.

Miranda turned away. It was just over eight months since Luke had packed up the toothbrush, the sketchbooks, the paint-flecked flannels, and the jeans bleached to that enviable state of softened whiteness he had left in her apartment. Over eight months since he’d told her that he’d decided to leave New York entirely and move to Berlin. “It’s got a totally happening art scene,” he’d said. “Really stimulating.” She hadn’t known until after he’d gone that some of the stimulation was being provided by an adorable, twentysomething German girl he’d picked up at a gallery in Chelsea and had been seeing behind Miranda’s back.

The lovers were still kissing; the man’s fingers wound through his girlfriend’s hair in an intimate, caressing gesture. Miranda did not want to see any more, so she walked down the platform. At the far end, under the stairs, was a huddled mass. At first glance, it looked like a pile of old blankets, but the bare foot sticking out from one corner—dark, with thick, overgrown nails and leatherlike heels—made it clear that someone was sleeping underneath. Reaching into her wallet, she extracted a five and tucked it at the edge of the pile. She also set down the doggie bag of shrimp and noodles that Bea had sent her off with. Then the train pulled in—finally—and Miranda turned from the foot and the blankets. She found a seat and sank down gratefully.

Ordinarily, she was happy with her job, but today there’d been nothing but stress. The managing editor had gotten into a fight with the decorating editor during the weekly staff meeting, which seemed to put the entire office in a foul mood. Two of her writers had failed to deliver promised copy, and a very labor-intensive banana malted milk torte was knocked to the floor during a photo shoot. It had to be made all over again, which completely threw off the schedule, and Marvin, the art director, had one of his hissy fits when he found out.

Miranda had been looking forward to an evening with her friends. But Courtney’s tactless comment had kind of ruined it for her; she felt flung right back in the misery that had been Luke. At least she could sleep in tomorrow. Her only commitment was not until four o’clock, when she’d agreed to meet Evan Zuckerbrot, the latest dish served up by eHarmony, for coffee. She had resisted signing up for eHarmony, but both Courtney and Lauren had been pestering her to just do it.

Miranda had succumbed, and even though she did not think Evan was that “someone special,” she reasoned that an afternoon latte would not be all that much of a risk. The rocking of the train was making her sleepy; she rested her head against the wall and closed her eyes. Just for a minute, she thought. Just one little minute. When she opened her eyes, she was still sitting in the subway car, entirely alone and freezing. She leaped up in a panic. Clearly, she had slept right past her stop, and several stops after that; she’d come to the end of the line. The doors were open and the platform was elevated; that’s why she was so cold. But where was she? Coney Island–Stillwell Avenue, that’s where—at least according to the sign.

Well, she’d just have to get a train going back; she could forget about finding a cab out here.

Miranda stepped onto the platform. Even from up here, she could smell the sharp, salt-laced wind coming from the ocean. It was a good smell, actually—clean and bracing. But she had to get home. She felt nervous being out so late by herself, a feeling that intensified when she went down the stairs. There were no longer any token booths, of course; she could see the phantom spot where the booth had been, its ghostly perimeter still outlined on the floor, like something from a crime scene. There was not a soul in the station, and she was just about to sprint up the stairs to the other side when her attention was snagged by a neat, cream-colored bundle that sat right by the banister.

She paused. It looked harmless enough—a folded blanket or something—but in the post-9/11 world, she had to wonder. Could a bomb be concealed in those folds? How would she know, anyway? Did she even have a clue as to what a bomb looked like? While she was debating this, she saw something else even more startling: a tiny foot peeking out from one corner of the blanket. It flitted through her mind that this was the second bare foot she’d seen tonight. Only this one belonged to a doll.

A doll. Not too likely there was a bomb in there. Miranda could see the little toes, all five of them, lined up like tiny brown nuts. What a well-made thing.

Clean too. Why would someone have thrown it away? Then the foot moved. Miranda stopped, not sure she saw what she thought she saw. She was exhausted, disoriented, and possibly a little drunk. The foot was an exquisite creation, crafted from something so smooth and pliant that she could not guess what it might have been. But when it moved again—this time causing the blanket on top to stir ever so slightly—she knew that it was no mere simulation. The cold she had been feeling ever since she woke up seemed to gather speed and force; it shot right through her, like a bullet. Carefully, she lifted a corner of the blanket away.

There, wrapped in a surprisingly clean white towel and cushioned by the bottom part of the blanket, was an infant. No, not an infant, anewborn, with cocoa-colored skin, black hair plastered to its tiny skull, and eyes that were tightly shut against the harsh light of the subway station. Oh. My. God. Was it even alive? Should she touch it? She remained that way for several seconds until the infant opened its mouth in a yawn that seemed to devour its entire face. The eyelids fluttered briefly before closing again. Definitely alive!

The yawn propelled Miranda into action. She lifted up the tiny creature. Under the towel the infant was naked; the umbilical cord, tied in a crude, red knot, looked as if it had been sawed off, and there were reddish streaks on her body. Was the umbilical cord infected or was it supposed to be that way? Miranda had no idea but wished she had some antibiotic ointment. Avoiding the red protuberance, she shifted the baby gingerly in her arms. Around one wrist was a bracelet; the small pink glass beads were interspersed with white ones whose black letters spelled out BABY GIRL. Someone had cared enough to place that bracelet on her wrist; was it the same person who had left her here in the station? Miranda wrapped the blanket around the infant’s body. But that didn’t seem sufficient, so she opened her coat and positioned her close to her own body. That ought to keep her warm. Or at least warmer.

The station was still empty. What should she do? There was an app on her phone that would help her locate a police station. But she did not want to be walking around here in this strange neighborhood by herself. No, she’d rather head for the station house back in Park Slope. She waited downstairs for the train; it would be warmer than the windy platform. When she heard it arriving, she hurried up the stairs and got in as soon as the doors parted.

As the train chugged along, it occurred to her that the infant might be hungry or thirsty. Hungry she could not fix. But she had a bottle of water in her bag; also hand sanitizer, which she wished she had thought to use earlier. Damn! Gripping the tiny body under one arm, she managed to squirt the green gel over both hands and rub furiously. Then she wet her fingers with the water and held them to the infant’s lips. She opened her mouth and began to suck. Tears welled in Miranda’s eyes. She was thirsty, poor little thing. Naked, abandoned in a subway station, and thirsty too—the final and crowning indignity in a brand-new life that so far seemed comprised of nothing but.

When they reached their stop, Miranda made her way through the dark streets toward the police station. At least the rain had tapered off. Against her body, the infant felt warm and animate. Miranda was keenly aware of her breath, in and out, in and out. The rhythm calmed her.

Yanking open the heavy doors to the station house, she stepped inside. A bored-looking officer behind a bulletproof shield was leafing through a copy of the New York Post; two other officers—one pale and seemingly squeezed into a uniform that was a size or two too small, the other as brown as the baby Miranda held close to her heart—were chatting in low voices. Above, the fluorescent light buzzed like a frantic insect. The cop reading the paper finally glanced up. He looked not at Miranda, but straight through her. “Can I help you?” he said in a tone that suggested he would sooner endure a colonoscopy, a root canal, and a tax audit—simultaneously.

“Look,” she said urgently, opening her coat to reveal the infant in its makeshift swaddling. “Look what I just found!”

TWO

“You thought it was a doll?” Courtney leaned over to reach for one of the cookies Miranda had baked—there were snickerdoodles, gingersnaps, and chocolate chip. The three of them were gathered in Miranda’s apartment on President Street. Bea would be here any minute; she promised to come in time for the local news broadcast that would be airing at five o’clock.

“The most lifelike doll I had ever seen,” Miranda said. She had canceled—well, all right, postponed—her meeting with Evan; she had been up most of the night and had slept virtually all day to compensate. Now her friends had come over to hear the story directly from her and to watch the news clip. “Also, I was still a bit looped and I wasn’t sure what I was looking at.”

“I would have been frightened,” Lauren said.

“Of what?” Miranda was about to reach for a cookie too but then stopped. She had three cake recipes she had to bake—and taste—this week; winter pounds were so easy to pack on, so hard to take off. Besides, it was the baking as much as the eating that appealed to her. She loved the visual and at times almost sensual interplay of ingredients, colors, and textures: the dense, golden clay of batter punctuated by the dark bits of chocolate, the pungent, earthy drip of molasses, the powdery loft of flour hitting the bowl.

“That something would happen to the baby while you were holding it. What if she had died while you were carrying her on the subway? The police might have charged you.”

“I never even thought of that,” Miranda said. She was still remembering the feeling of the infant pressed so close to her; they seemed to fit, like puzzle pieces, so neatly together. Is this what new mothers experienced when their babies were handed to them? Well, not thatinfant’s mother; clearly she had not felt that sense of completion when holding her baby. But Miranda was more sympathetic—and even curious—than judgmental. What could have driven her to do such a thing? What impossible place—all other options exhausted, rejected, used up—had she reached to make her decision? The blanket and the bracelet showed she had made some effort. Though leaving the baby in a subway station . . . well, it was pretty hard to put any positive spin on that.

The bell rang, and there was Bea, corkscrew curls massing around her face, running up the stairs. “Hell-o!” she said, plopping down on Miranda’s rug with a big shopping bag from Duane Reade. “I brought provisions!”

“Let me see,” said Courtney, peering into the bag. “Chips, pretzels, macadamia nuts, chocolate . . .” She looked up at Bea. “Is there anything you didn’t buy?”

“Well, we’re going to watch the news; I figured we’d need fortification.”

“Bea, the clip is going to last, like, three minutes,” Courtney said. “This isn’t exactly a double feature.”

“And I made cookies,” Miranda added.

“You always make cookies!” said Bea. “But doesn’t watching TV make you hungry?” She reached for a bag of chips and opened it in a single, deft stroke.

“Look, it’s going to start!” Lauren said, squeezing Miranda’s arm. “Turn the sound on.”

The reporter, a tall, glib guy who resembled a Ken doll, shoved the microphone in her face. “We’re here, live in Brooklyn at the Seventy-eighth Precinct with Amanda Berenzweig—”

“Miranda,” her on-air incarnation corrected.

“Excuse me?” Patter interrupted, Ken looked baffled.

“Miranda, the name is Miranda Berenzweig.”

“Of course it is,” he said with his dazzling smile. “Now, can you tell us what happened, Ms. Berenzwig? Right from the beginning?”

“You didn’t correct him that time,” Courtney noted.

“I thought he might cry if I did.”

“Shh,” said Bea. “I can’t hear.”

The talking stopped, and Miranda settled back to watch her televised self explaining what had happened: falling asleep in the subway, waking in an unfamiliar station, the doll-that-turned-out-be-a-baby. Then the camera cut away to the baby herself—now cleaned up and wearing a little cap over her head. If anyone has any information, please call . . . flashed along the bottom of the screen. Then some more blather from Ken and the segment was over. A commercial for a new breakfast cereal chirped across the airwaves until Bea clicked the remote to mute it.

“So what’s going to happen to her now?” Lauren asked. Of the four friends, she was the only one with children.

“Foster care, I guess. Until someone claims her. If someone claims her,” said Miranda.

“Someone will claim her,” Lauren said as she buttoned her coat. “You wait.”

The rest of them sat around discussing it after she had left. Bea had been right: they polished off the cookies, the chips, the nuts, the pretzels, and almost all the chocolate. “Who wants the last square?” Bea said. Miranda wavered and was glad when Courtney spoke up. When she and Bea got up to leave, Miranda gave them each a hug. She had even forgiven Courtney—sort of. “Thanks for coming,” she said. “I was so glad you were here.”

“Of course we were here,” Bea said. “Where else would we be?”

* * *

Over the next couple of days, Miranda found herself thinking about the baby. She thought about her as she baked those three cakes and while she edited the two late articles that finally showed up days past their respective deadlines. She thought about the baby in the shower, when she went out for a run in Prospect Park, and when she worked her shift at the food co-op on Union Street.

She also thought about the baby’s mother. She first pictured her as a teenager, petrified to tell her parents she was pregnant. Or maybe she was a drug addict or an alcoholic. Miranda remembered the blanket, the towel. Whoever she was, the mother had tried, sort of. But why the subway station and not a hospital or a police station?

There were no answers to these questions. But she might be able to find out more about the baby. She returned to the police station where she’d first brought her. The once-bored cop now greeted her like a long-lost cousin. “You!” he said, smile wide and welcoming. “You’re the one who found the baby!”

She nodded, oddly pleased. “I am. And I was wondering what happened to her since then.”

The officer was only too glad to fill her in. She got the address of family court and the name of the judge assigned to the case. The building, at 330 Jay Street, was not all that far from her office in downtown Manhattan. The next day, she made the trip and, after a few inquiries, found the courtroom she’d been looking for. The metal benches just outside were packed, and the waiting sea of faces looked sad, angry, embittered, or a ravaged combination of all three. Miranda stepped inside the courtroom and slid into a seat at the back. Up front, Judge Deborah Waxman was presiding. She looked to be in her sixties, with frosted blond hair, frosted pink lip gloss, and frosted white nails—it was like she was sugarcoated. But nothing about her manner or voice was even remotely sweet. She cut through the whiny excuses, the meandering stories, the bluster and the rationalizations made by deadbeat dads and criminally negligent moms with the same brisk, impartial efficiency in a way that Miranda found intimidating but admirable. When she called a ten-minute recess, Miranda asked a court officer if she could approach the bench. The officer looked at the judge who looked at Miranda. She felt herself being intensely scrutinized and was relieved when the judge inclined her head in a small nod. She had passed.

“What can I do for you?” asked the judge.

Miranda knew she did not have much time. “I’ve come about the baby,” she said. “The one who was found in the subway at Stillwell Avenue.”

“Stable condition at a city hospital,” the judge said succinctly. “When she’s been thoroughly checked out, she’ll be released.”

“Where to?”

“Family services is arranging for a foster care placement. No one has claimed her, so she’ll be put up for adoption.” Judge Waxman looked down as if assessing the condition of her iridescent manicure. “Why do you want to know?”

“I’m the one who found her that night,” Miranda said. “I brought her to the police.”

“You did.” It was a statement, not a question.

“Yes, Your Honor.”

“That was a very kind thing to do.” The judge brought her gaze up from her nails. Her small but intensely blue eyes seemed to be taking Miranda’s measure.

“No, it wasn’t,” said Miranda, meeting that gaze full-on.

“You think it was unkind?” Judge Waxman sounded surprised.

“It was no more than decent,” Miranda said. “And decent is not the same as kind. Decent is what anyone would have done.”

“Not her mother,” said the judge.

“No, well, I’m sure there’s a story behind that. . . .”

“Isn’t there always?” The judge glanced at her watch. “Recess is over,” she said. “Thank you for coming, Ms. . . .”

“Berenzweig.”

“Ms. Berenzweig. I’ll see that the mayor’s office sends you a citation or something.”

“I don’t want a citation,” Miranda said.

“No? Then what do you want?” It was a challenge.

Miranda felt flustered. Did she even know? “Just to know that she’s all right,” she said.

As it turned out, that was not enough. Now that she knew the baby was being cared for, Miranda craved more information. She was such a thirsty baby. Would someone make sure she drank enough? What about a name? Names were so important; Miranda hoped she wasn’t given one that was silly or demeaning.

Over the next week, Miranda returned to Judge Waxman’s courtroom three more times. Each time, she waited patiently for a recess or a break and would listen to the update that Judge Waxman delivered in the same clipped tone. The baby was drinking formula. The baby had gained an ounce. There was some evidence of drugs—she would not specify—in her system, but they were minimal; it did not appear that her mother had been an addict. Miranda warmed to the woman, frosting and all. How would the judge have known these details unless she too had taken a special interest in the baby?

Then Judge Waxman told her that a foster care placement had been found for the baby; she would be leaving the hospital shortly.

“Would I be able to see her before they let her go?” Miranda asked.

“Whatever for?” Judge Waxman’s brows, two thin, penciled arcs, rose high on her forehead.

“Just because. Maybe I could hold her. The nurses must be so busy; they might not have time.”

“I’ve never had a request like that,” said the judge. Miranda did not say anything; she just waited while those shrewd blue eyes did their work. “But I see no reason why you couldn’t. Come back tomorrow; I’ll give you the name of the facility and a letter allowing you to visit with her at the discretion of the nurses.”

“Oh, thank you!” Miranda said. “Thank you so much!”

She walked out of the courthouse buoyant with anticipation, and after work spent an hour in Lolli’s on Seventh Avenue, considering the relative merits of tiny sweaters, caps, dresses, and leggings. She spent way too much money, but rationalized her purchases as charitable contributions.

The baby was being held at Kings County Hospital, on Clarkson Avenue; Miranda took the subway to the 627-bed facility (she had looked it up online) after she left work the next day. The two nurses on the neonatal ward were only too happy to indulge her. “Honey, you can hold her all night long if you want to,” said one, her Caribbean accent giving the words a musical lilt.

“Do you know that someone found her in the subway?” said the other one.

“I know,” Miranda said. “I was that someone.”

“Lord, no!” said the nurse.

Miranda nodded and looked down at the baby. She was definitely heavier; Miranda felt she had her weight imprinted somewhere in her sense memory and she could discern the difference. Her skin tone had evened out and her dark eyes were open and fixed on Miranda’s face. Did she remember the time they had spent together? Could she in some inchoate way recognize her?

Miranda spent the next two hours walking, rocking, and talking to the baby. She took scads of photos that she would later post to her Facebook page. The baby guzzled the bottle of formula that the nurses prepared, and she dozed peacefully as Miranda toted her up and down the hospital corridor. During a diaper change, which the nurse showed Miranda how to execute, she blinked several times and kicked her tiny feet. As her hand closed around Miranda’s extended finger, the force of her grip was a revelation.

When visiting hours ended, Miranda pulled herself away with the greatest reluctance. She went back the next night, this time with butterscotch blondies she had baked from an office recipe; the nurses tore into them eagerly. “For someone who had such a start, she’s doing all right,” said the one with the island accent. She bit into her blondie with evident delight.

“She’s lucky you’re the one who found her,” said the other.

“Maybe I’m the lucky one,” Miranda said, gazing down at the baby who was now wearing a knit dress adorned with rosebuds; Miranda had rubbed the cotton against her own cheek to test for softness when selecting it.

The following day, Miranda was back in Judge Waxman’s courtroom. “The family that adopts her—they’ll be thoroughly checked out, right?” she asked.

“Of course,” said Judge Waxman. “We have our protocols, and they are strictly adhered to.”

“Will they love her, though? How can your protocols determine that?”

Judge Waxman pursed her shiny lips in what looked like irritation. But when she spoke, it was with more gentleness than she had previously displayed. “What about you, Ms. Berenzweig?” she asked.

“Excuse me?”

“What about you as a prospective foster parent? With the goal of adoption?”

“Me?” Miranda’s hopes lifted briefly at the thought before they came plummeting down again. How could she even consider adopting a baby? She had no husband, no boyfriend even, and an already-demanding job that was about to become even more demanding.

“Yes, you,” Judge Waxman was saying. “I think you’ve demonstrated a remarkable attachment to this infant already. How many times have you been to see me about her? And how many times have you been to see her?”

“Well, she’s such a darling little thing, and of course I was concerned about her, having found her and everything—” She was babbling, babbling like an incoherent fool. She took a deep, centering breath and began again. “Doesn’t it all take time?” she said. “Aren’t there protocols?”

Again that shrewd, raking look from the judge. “Of course there are. But in cases of urgent need, and this certainly qualifies, I have ways of . . . expediting things when I need to. We could conduct a home visit, and if everything is found to be in order, we could place her with you and begin the adoption proceedings. It would take a few months, but in the meantime you’d be fostering her and getting to know her better.”

I already know her, Miranda wanted to say. But that seemed, well, crazy. So she kept quiet.

“Why don’t you sleep on it?” Judge Waxman asked. “Think it over. Talk to your family. Your friends. And give me your answer in the next few days.”

Miranda nodded and left. Isn’t this what she’d been hoping for, wishing for, in some way scheming for since the first time she’d shown up in front of Judge Waxman? Now that the offer was actually on the table, though, she was petrified, and she walked out of the building bathed in a pure, icy panic. Rather than take the subway, she decided to walk for a while; she needed to clear her head.

The day was sunny and not too cold; there were lots of people on the pedestrian path of the Brooklyn Bridge. Miranda had to maneuver past power walkers, joggers, women with strollers, old couples with thick-soled shoes and Polar fleece jackets, and an excited, noisy bunch of school kids, all wearing identical neon orange vests. Below, the water shifted and sparkled; a flight of birds—she had not a clue as to what they were—sliced the sky above.

The new Web site about to launch at Domestic Goddess meant that in addition to her current workload, Miranda would now be overseeing all the online food content—more recipes that needed testing, more features that needed assigning, more deadline-averse writers. It was a step-up in responsibility, prestige, and scope. It would also mean a lot more work, especially in the beginning. How would she manage all that, on her own, with a brand-new baby? And the baby looked to be black. Maybe she would be better off with a different sort of family—a family with two parents, or a family in which at least one of them had skin her color.

Once across the bridge, Miranda walked west until she reached Greenwich Street and started heading uptown. Assuming she could clear the racial hurdle—Judge Waxman, after all, had not even raised the issue—could she afford to hire a sitter? Or would she need to resort to daycare? What would her father say? Her landlady and her colleagues at work? Her friends? She had a hunch that Courtney was going to rain right down all over her parade. What was it with her lately anyway? Was it just the engagement, or was it something deeper, more systemic?

Her father. She realized she hadn’t talked to him for more than a week. But given the fog of dementia that enveloped him, it didn’t seem to matter how often they spoke because he was not there when they did. Still, she had to try, and she took her phone from her purse. His caretaker, Eunice, answered, and after giving Miranda a brief update, she handed over the phone. “Nate, it’s your daughter,” Eunice was saying in the background. “Your daughter, Miranda—you remember?”

“Miranda?” her father said uncertainly. “Do I know you?”

“Of course you know me, Dad.” She closed her eyes, just for a second, as if her sorrow were a visible thing she deliberately chose not to see. “I’m your daughter. Your girl.”

“There are no girls here. No girls.” His voice quavered. “I like girls—little girls, big girls. Girls are very, very nice. I think I used to have a girl once. What happened to her?” Now he sounded ready to cry.

“Dad! You still do! I’m that girl—it’s me, Miranda.”

“You’re not a girl,” he chided. “No, no, no. And Miranda—that’s not a girl’s name. I would have called a girl Rosie or Posy. Maybe Polly. But never Miranda.”

There was a silence during which Miranda swiped at her tear-filled eyes. She had come to the mini-freeway that was Canal Street and did not answer until she’d crossed safely to the other side. But when she attempted to prod her father’s ruined memory again, it was Eunice who replied. “He’s having a bad day.”

“I can tell.”

“Some days he knows your name and everything. He remembers where you live and when you’re coming to visit.”

“But not today.”

“Not today,” Eunice said. “Why don’t you try again tomorrow?”

“I will.” She put the phone back in her purse and descended the stairs to the subway station. While on the train, Miranda took unsentimental stock of her life: eight years at a good job and a recent promotion, a nice apartment, money from both her salary and a small inheritance from her grandmother, a father sinking deeper into the oblivion of his disease. Good friends, no boyfriend, and apart from a date with a man she’d never actually met, none on the horizon either.

She had not been thinking about having a child when she first happened on the abandoned baby on the platform. But once she’d seen her, held her, everything changed. The very act of finding her seemed significant, so by extension, all the events leading up to it—falling asleep and missing her stop, waking up in that particular station, passing by that spot at exactly that moment—glowed with significance too. She’d found a baby. How not to believe that in some way that baby was meant—even fated—for her?

But was she equal to the job? Growing up, Miranda had not been especially close to her own mother. Her strongest bond had been with her father. Then she’d gone through that typical rebellious phase in her teen years, and before she’d ever had a chance to circle back and know or understand her in any more adult way, her mother had gotten sick. And died. Yet these last few weeks had opened new possibilities, new horizons. Maybe she did have it in her to do it all differently, to form the kind of attachment that she had longed for in her own childhood. At the very least, she wanted to try.

Suddenly she felt energized and, when she reached the Domestic Goddess office on West Fourteenth Street, Miranda bypassed the elevator and took the stairs to the fifth floor. She wasn’t even winded when she arrived. No, she was pumped, primed, and ready for the biggest challenge she’d ever faced. She’d sleep on it, of course. And then if she felt like this—so certain, so committed, so excited—tomorrow, she would contact Judge Waxman to tell her the answer was yes.

THREE

Bea and Lauren showed up the following Sunday morning to help her prepare for the upcoming inspection from Child Welfare Services. Bea was organized and unsentimental, ruthlessly jettisoning yellowed plastic containers, wire hangers, and the broken sewing machine Miranda had lugged in from the street a decade ago and never had fixed. Lauren, by virtue of the fact that she had kids, could be counted on to spot hazards that posed a threat to child safety. Courtney was ring shopping with the insufferable Harris but said she would try to stop by later. As Miranda had intuited, she was the only one who seemed less than enthusiastic about the plan. Miranda brushed her concerns away; Bea and Lauren were right there with her.

By the end of the day, Miranda’s sunny top-floor apartment was in peak condition. Unworn clothes were bagged and prepped for the Goodwill truck, and weeded-out books for the library. Clutter and old papers had been tossed, filed, or recycled. And the place was squeaky clean, from top to bottom, inside and out. When Miranda had tried to shove some of her knitting supplies into a closet—everyone at Domestic Goddess, even Martin, had taken a knitting pledge—Bea had nixed the idea. “They’re going to look in the closets,” she said. “And in the medicine chest, kitchen cabinets—everywhere.”

“Does that mean I have to give up knitting?” Miranda said. She had hardly gotten started.

“No. We just have to turn your stuff”—she gestured to the skeins of yarn—“into decor.” To that end, she repurposed a basket Miranda had been planning to dump and artfully arranged the yarn into a display of pleasing textures and colors. The needles she gave to Miranda. “High up for these. Top shelf.”

“But it makes more sense to keep them with the yarn.”

“Are you kidding?” Lauren said. “She’s right—knitting needles could be lethal weapons. Get them out of sight. Now.”

Miranda meekly complied. Then she ordered pizza and opened a bottle of wine while they waited for it to arrive. Glass in hand, she looked around at her reconfigured apartment. The desk had been moved into the living room; she’d been persuaded to part with a poorly made bookcase, as well as many of the books in it, to make more room. “But not these; these are special.” Miranda stood protectively in front of a pile she’d saved from the discards.

“They look like kids’ books anyway,” said Lauren.

“They are.” Miranda picked up a copy of The Poky Little Puppy, which had beenpublished in 1942. “They’re all old, though. Some were mine when I was little; my mother had saved them. After she died, I couldn’t bring myself to get rid of them. And when I’d see an old book I liked at a sale or a flea market, I’d buy it. I didn’t really think of it as collecting until about five years in.”

Lauren knelt in front of the pile. “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. The Velveteen Rabbit. A Child’s Book of Fairy Tales—look at these illustrations; they’re wonderful.”

“Those are by Arthur Rackham. He’s one of my favorites.”

“You’ll have such fun reading these together.” Bea was looking at Noël for Jeanne-Marie; one of the central characters was a sheep named Patapon. “She’ll have a ready-made library when she gets here.”

“You mean if she gets here.” Miranda sneezed; some of those books hadn’t been touched in a long while and were dusty. “It’s not a sure thing yet.” She reached for a cloth and dusted off Joan Walsh Anglund’s A Child’s Year. This was one of the books she had owned and loved; her name, written in red crayon, was still on the inside cover. Maybe there would be another name added to this book one day—the name of the little girl she hoped would come to live with her.

Miranda began stacking the books in the closet. She could have used that bookcase she was about to jettison, but she needed the space for something even more essential—the crib that Lauren’s babies had used, rescued from its basement limbo, reassembled, and wiped down thoroughly with nontoxic cleanser. “I’ll give it back to you when she’s through with it,” Miranda had said.

“Not necessary. The shop is closed; I’m done.” Lauren patted her midsection for emphasis.

Everything else in what had been the tiny study was left pretty much intact: the small armchair she had used for reading would be perfect for feeding the baby; the pine cupboard that had contained recipes, clippings, and back issues of Domestic Goddess had been emptied in preparation for the baby’s clothes. The artwork on the walls—a poster of a still life by Matisse, another of musicians by Picasso, an oddball painting of an owl picked up at a local stoop sale—all seemed perfectly appropriate for the baby’s eyes.

The baby. My baby. Every time she said or thought those words, they did not seem real. How would it feel to move from a single state to a coupled one? For even though people talked about single moms so casually now, as if it were simply another lifestyle choice in an array of many possible choices, how could a mother ever be considered single? Didn’t having a child preclude all sense of singleness? Didn’t being a mother make you part of an indissoluble binary unit?

Her own mother had seemed to chafe at that connection; she was always urging Miranda to go and play. Her best friend in those years, Nancy Pace, had a mother who flopped down on the floor and embarked on marathon games of Candy Land, Monopoly, and Parcheesi with her daughter and her friends; they baked together and Mrs. Pace had taught Nancy to sew on a Singer machine she set up on the kitchen table. Miranda had longed for that mother.

The downstairs bell buzzed. “Pizza,” said Miranda.

“Good,” said the ever-hungry Bea. “I’m famished.”

But it wasn’t the delivery guy after all. It was Courtney, all artlessly-artfully tousled blond hair and chic black coat.

“Did you get the ring?” asked Lauren eagerly.

“I want to see it,” added Bea.

Courtney shook her head. “No. We didn’t find it today. But look what we did find.” She twisted her hair into an impromptu ponytail so that the small, flower-shaped earrings—diamonds and rubies from the look of them—that twinkled on her lobes were more visible.

“Nice!” said Bea.

“Are they real?” Lauren asked, getting closer.

Miranda stood back. She was ashamed of the small, hot rush of envy she suddenly felt. Courtney had been her roommate and best friend freshman year; Bea and Lauren joined them later. It was Courtney who had seen Miranda through numerous all-nighters, boyfriends, and breakups, dreary jobs, and her mother’s hideous death from colon cancer. But things had changed somehow, and she now seemed to regard Miranda with an annoying mixture of pity and disdain. The engagement had only made it worse. You’d think no one in the history of the world had ever planned a wedding before.

When Lauren and Bea finally stopped cooing over the earrings, Courtney looked around the apartment. “It looks great in here,” she said approvingly. “I love what you’ve done.”

“Thanks,” Miranda said, relaxing a little. Maybe she was as guilty of overreacting to Courtney’s comments as Courtney was guilty of obtuseness in making them. The two of them did go way back.

“You should bake something,” said Lauren, who had recently purchased an apartment and was the veteran of a dozen or more open houses. “Use apples and cinnamon. And don’t forget to have fresh flowers on the table, even if they’re only a six-dollar bunch of tulips from the corner store.”

“Are you staging Miranda’s apartment?” Bea asked.

“Why not? It works with prospective buyers; I’ll bet it will work with whoever they send tomorrow.”

“I don’t think you have to worry so much,” said Courtney. She let her hair fall down again; the earrings disappeared. “It’s just for a foster care placement. They won’t be scrutinizing you so carefully.”

There was an uncomfortable silence before Miranda spoke up. “Actually, that’s not true. The foster care placement comes first, of course, but Judge Waxman considers it just a temporary stop on the road to adoption. And so do I.”

“Miranda,” said Courtney. “How do you think you’re going to pull this off? I mean, your place is cute and all, but you can’t seriously believe you can raise a child here.” The patronizing tone was back at full blast.

“People do it with a lot less,” said Bea.

“And Miranda could eventually move,” Lauren pointed out. “Remember—promotion? Raise?”

“That’s another thing,” Courtney said. “How are you going to deal with all the pressure of a new job and a new baby? Even women who are married have trouble managing—”

“Maybe women who are married aren’t as motivated as I am. I’m thirty-five, and I just broke up with my boyfriend. This may be my last chance to have a baby.”

“Don’t you think you’re being a bit self-dramatizing? Irresponsible even?” Courtney pushed her hair back, and the earrings twinkled anew. “Maybe this is all a reaction to Luke and you need to slow down a little to think it over. Adopting a baby is a huge deal.” She turned to Lauren. “Back me up here, would you? I mean, didn’t we just have this conversation last night? You agreed with me then.”

Miranda stared at Lauren, whose face had turned a damning shade of pink. So Courtney and Lauren had together decided that she wasself-dramatizing and irresponsible.

“I’m sorry,” Lauren said. “I do think Courtney has a point, but I’m behind you one hundred percent. We all are.”

Copyright © 2014 by Michael Mcdonough. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.