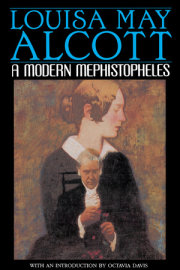

"I tell you I cannot bear it! I shall do something desperate if this life is not changed soon. It gets worse and worse, and I often feel as if I'd gladly sell my soul to Satan for a year of freedom."

An impetuous young voice spoke, and the most intense desire gave force to her passionate words as the girl glanced despairingly about the dreary room like a caged creature on the point of breaking loose. Books lined the walls, loaded the tables and lay piled about the weird, withered old man who was her sole companion. He sat in a low, wheeled chair from which his paralyzed limbs would not allow him to stir without help. His face was worn by passion and wasted by disease but his eyes were all alive and possessed an uncanny brilliancy which contrasted strangely with the immobility of his other features. Fixing these cold, keen eyes on the agitated face of the girl he answered with harsh brevity, "Go when and where you like. I have no desire to keep you."

"Ah, that is the bitterest thing of all!" cried the girl with a sudden tremor in her voice, a pathetic glance at that hard face. "If you loved me, this dull house would be pleasant to me, this lonely life not only endurable but happy. The knowledge that you care nothing for me makes me wretched. I've tried, God knows I have, to do my duty for Papa's sake, but you are relentless and will neither forgive nor forget. You say `Go,' but where

can I go, a girl, young, penniless and alone? You do not really mean it, Grandfather?"

"I never say what I do

not mean. Do as you choose, go or stay, but let me have no more scenes, I'm tired of them," and he took up his book as if the subject was ended.

"I'll go as soon as I can find a refuge, and never be a burden to you anymore. But when I am gone remember that I wanted to be a child to you and you shut your heart against me. Someday you'll feel the need of love and regret that you threw mine away; then send for me, Grandfather, and wherever I am I'll come back and prove that I can forgive." A sob choked the indignant voice, but the girl shed no tears and turned to leave the room with a proud step.

The sight of a stranger pausing on the threshold arrested her, and she stood regarding him without a word. He looked at her an instant, for the effect of the graceful girlish figure with pale, passionate face and dark eyes full of sorrow, pride and resolution was wonderfully enhanced by the gloom of the great room, the presence of the sinister old man and glimpses of a gathering storm in the red autumn sky. During that brief pause the girl had time to see that the newcomer was a man past thirty, tall and powerful, with peculiar eyes and a scar across the forehead. More than this she did not discover, but a sudden change came over her excited spirit and she smiled involuntarily before she spoke.

"Here is a gentleman for you, Grandfather."

The old man looked up sharply, threw down his book

with an air of satisfaction, and stretched his hand to the stranger, saying bluntly, "Speak of Satan and he appears. Welcome, Tempest."

"Many thanks; few give the Evil One so frank and cordial a greeting," returned the other, with a short laugh which showed a glitter of white teeth under a drooping black mustache. "Who is the Tragic Muse?" he added under his breath as he shook the proffered hand.

``Good. She is exactly that. Rosamond, this is the most promising of all my pupils, Phillip Tempest. The `Tragic Muse' is Guy's daughter, as you might know, Phillip, by the state of rebellion in which you find her!"

The girl bowed rather haughtily, the man lifted his brows with an air of surprise as he returned the bow and sat down beside his host.

"Ring for lights and take yourself away," commanded the old man, and Rosamond vanished from the room, leaving it the darker for her absence.

For half an hour she sat in the great hall window looking out at the waves which dashed against the rocky shore, thinking sad and bitter thoughts till twilight fell and the outer world grew as somber as the inner one of which she was so weary. With a sigh she was about to rise and seek her own room when a sudden consciousness of a human presence nearby made her turn to see the newcomer pausing just outside the old man's door to regard her with a curious smile. An involuntary start betrayed that she had entirely forgotten him, a slight which she tried to excuse by saying hastily, "I was so absorbed in watching the sea I did not hear you come out. I love tempests and--"

He interrupted her with a short laugh and said in a deep voice which would have been melodious but for a satiric undertone which seldom left it, "I am glad of that, for your grandfather invites me to pass the night, and I shall do so willingly since my young hostess has a taste for tempests, though I cannot promise to be as absorbing as the one outside."

In the fitful light of the dusky hall the newcomer's face suddenly appeared fiery-eyed and menacing, and, glancing at a portrait of Mephistopheles, Rosamond exclaimed, "Why, you are the very image of Meph--"

Tempest strolled to the picture which hung opposite the long mirror. Looking up at it, a change passed over his face, an expression of weariness and melancholy which touched her and made her repent of her frankness. With an impulsive gesture she put out her hand, saying in a tone of sweet contrition, "I beg your pardon; I've been very rude, but I live so entirely alone with Grandfather, who is peculiar, that I really don't know how to behave like a well-bred girl. I had no wish to be unkind; will you forgive me?"

"I think I will on condition that you play hostess for a little while, for your grandfather begs me to pass the night and gives me into your care. May I stay?"

He held her hand and spoke, looking down into the beautiful face which was so unconscious of its beauty. A hospitable smile broke over her wistful face and with a word of welcome she led him away to a little room which overhung the sea. Placing him in an easy chair, she stirred the embers till a cheery blaze sprung up, lighted a brilliant lamp, drew the curtains and then paused as if in doubt about the next step.

"I always have tea here alone and send Grandpapa's up. Will you take yours with him or with me?"

"With you if you are not afraid of my dangerous society," he answered with a significant smile.

"I like danger," she said with a blush, a petulant shake of the head and a daring glance at her guest.

Ringing the bell, she ordered tea and when it came busied

herself about it with the pretty earnestness of a child playing housewife. Lounging in his easy chair, Tempest regarded her with an expression of indolent amusement, which slowly changed to one of surprise and interest as the girl talked with a spirit and freedom peculiarly charming to a man who had tried many pleasures and, wearying of them all, was glad to discover a new one even of this simple kind. Though her isolated life had deprived Rosamond of the polish of society, it had preserved the artless freshness of her youth and given her ardent nature an intensity which found vent in demonstrations infinitely more attractive than the artificial graces of other women. Her beauty satisfied Tempest's artistic eye, her peculiarities piqued his curiosity, her vivacity lightened his ennui, and her character interested him by the unconscious hints it gave of power, pride and passion. So entirely natural and unconventional was she that he soon found himself on a familiar footing, asking all manner of unusual questions, and receiving rather piquant replies.

"So, like `Mariana in the moated grange,' you are often `aweary, aweary,' and wish that you were dead I fancy?" he said, after a series of skillful questions had elicited a history of the solitary life she had led. To his surprise she replied with a brave bright glance that betrayed no trace of sentimental weakness in her nature, but an indomitable will and a cheerful spirit.

"No, I never wish that. I don't intend to die till I've enjoyed my life. Everyone has a right to happiness and sooner or later I

will have it. Youth, health and freedom were meant to be enjoyed and I want to try every pleasure before I am too old to enjoy them."

"I've tried that plan and it was a failure."

"Was it? Tell me about it, please." Rosamond drew a low seat nearer with a face full of interest.

. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.