Tivoli

Spring, even in America, is Japanese. It is not only the leaves that grow. Shadows grow also. Everything grows, both what receives the light, and what is cast by it. There is more in the world, all of it proliferating like neural patterns. Almost all of it: it is also the most melancholy season, for, as Alkman says, there is nothing to eat. Resurrection is far too close to death, and the moment when the sleep begins to leave your eyes is the most fragile, the most porous, for at times in spring, even the emotional granaries are depleted.

I remember the lines from Sans Soleil: “Newspapers have been filled recently with the story of a man from Nagoya. The woman he loved died last year and he drowned himself in work—Japanese style—like a madman. It seems he even made an important discovery in electronics. And then in the month of May he killed himself. They say he could not stand hearing the word ‘Spring.’ ”

Lagos

One sense of sleep is the disappearance of the eyes. The head turns inward, toward darkness. Another is an entry into a state of being carried. Outside a church in Lagos, a man sleeps. The body transitions from carrying itself across the earth into being carried by it, into giving itself up to that. The body of Christ is on the now-lowered cross. A white cloth is draped around him. He is not dead, only sleeping (a sleep of two nights and one long day). Around him at the moment of descent are John the Beloved, Joseph of Arimathea, Nicodemus, Mary Magdalene. Closest to him is his mother, in white. John holds out a larger white cloth with which to receive his body. The earth carries the cross. The cross carries the body. The body on the cross carries the world: in a state of sleep, one common dream is that of superhuman strength. It is said (in the Orthodox tradition) that the True Cross is made of cedar, pine, and cypress.

It is said (by Calvin) that were all the fragments of the True Cross held in all the reliquaries of all the cathedrals of Europe to be assembled, an entire ship would be filled with the gathered wood. In sleep, one form of vision is foreclosed, and another becomes available. Outside an Anglican church in Lagos, the sleeping Christ dreams of sustenance and levitation.

Btouratij

The texture of memory and the texture of dreams are curiously similar: an intense combination of a freedom verging on randomness and a specificity that feels oneiric.

Most narratives of dreams simply don’t work, on a technical level, while most dreams do narratively “work” as dreams. You don’t have a dream and think, “That was not a dream.” But often when you read about a dream, or see a depiction of one, you feel like you’re reading about or seeing something that isn’t a dream.

Nuremberg

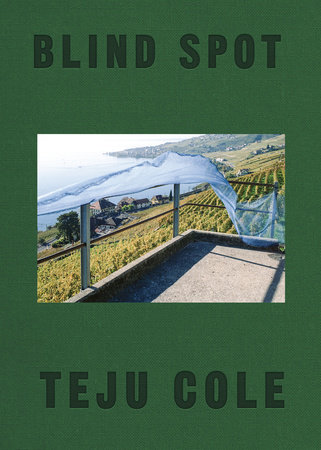

In the spring of 1507, Albrecht Dürer returned from his second trip to Italy. He had seen Leonardo’s oil sketches, and been impressed by their use of drapery to suggest form, movement, wind, and light. A folded drapery is cloth thinking about itself. Under pressure from itself or the influence of external agents, a material adopts a topographical surface. A material, around the axis of itself, faces some part of itself, and confounds its inside and outside.

A drapery study of Dürer’s from 1508 shows the influence of a sketch of Leonardo’s from about two decades earlier. Folding: “falten”: to bring something together, and also to iterate that bringing together: a joining and a repetition. In the crumples, pleats, gathers, creases, falls, twists, and billows of cloth is a regular irregularity that is like the surface of water, like channels of air, like God made visible. The human is the divine enfolded in skin. (There is a curious comment about folds in John’s account of the Resurrection: a folded cloth that remained folded even as events unfolded: “Then Simon Peter came, following him, and went into the tomb. He saw the linen wrappings lying there, and the cloth that had been on Jesus’ head, not lying with the linen wrappings but rolled up in a place by itself.”) In Nuremberg, almost within sight of Dürer’s house, I saw, about eight minutes after they began their stellar journey, some several rays of the sun describing the folds on the curtains of my hotel room.

Auckland

Tane and his siblings conspire to push apart their mother, Papatuanuku, the earth, and father, Ranginui, the sky. In the space forced between the two is the light of the world. The light falls and flows between two eyelids.

Muottas Muragl

They used to burn women here. In these peaceful-looking cantons, women accused of consorting with the Devil were executed in the most sadistic ways imaginable, for God’s greater glory. Now the landscape is long settled, like a reputation. The eye scans and organizes the folded mountains. All is at peace. Nevertheless, in one enciphering corner of my mind I believe still that every line in every poem is the orphaned caption of a lost photograph. By a related logic, each photograph sits in the antechamber of speech. Undissolved fragments of the past can be seen through the skin of the photograph. The tectonic plates are still busy in their rockwork, and there is a faint memory of burning ash. The difference between peace and mayhem is velocity.

Piz Corvatsch

One of the smallest things in this picture—the reddish mound at the southwest corner of the red mesh—is in reality one of the largest. The picture was made at three thousand feet on Piz Corvatsch in the Engadin, and that wine-dark smudge is one of the great peaks of the Bernina Alps. From this point of view, it is about the same size in terms of area as the last small parcel of summer snow on the scree. Both are far smaller than the open shadows cast on the bottom left by unseen railings. Corvatsch was Nietzsche’s favorite mountain, and maybe a line from Ecce Homo could caption this picture: “Philosophy means living voluntarily among ice and high mountains.”

But maybe not. Something less strident is needed for an inventory picture like this one, in which no square centimeter is allowed to lord it over any other one, just as we learn in school that a kilo of iron miraculously always weighs the same as a kilo of feathers. Instead of philosophy, this is a picture of fact: siding, poles, mesh, sky, mountain, gravel, railing, and shadow, as well as color, angle, horizon, and loss of balance.

Capri

Later on, I thought of the catalogue of ships in the Iliad. “I could not tell over the multitude of them nor name them, / not if I had ten tongues and ten mouths, not if I had / a voice never to be broken and a heart of bronze within me, / not unless the Muses of Olympia, daughters / of Zeus of the aegis, remembered all those who came beneath Ilion.” But that was literary, that came later. On the day itself, on the evening of the morning in which I opened up the window of my room to see the apparition of a shining fleet on the Mediterranean, what I thought of was what Edna O’Brien said to those of us in the audience: “We know about these beautiful waters that have death in them.”

McMinnville

In February 1930, a man and a woman were involved in a car accident, the man died instantly. The woman, his wife, not long after. She’d been pregnant. Their son, raised in an orphanage, became an industrialist, founded an aviation company, and died at age eighty-four in 2014.

In March 1995, a former fighter pilot died in a car accident before his thirtieth birthday. His grieving father, who had founded an aviation company and was to die many years later at the age of eighty-four, in 2014, was said by locals to have been CIA, a charge he never confirmed or denied, saying only that it was better than being KGB.

Tripoli

The date to remember is 1654. He paints The Goldfinch that year. The color harmonies are cool, the wall is as full of subtle character as a face. His life is like a brief and beautiful bridge. He studies with Rembrandt in Amsterdam. He teaches Vermeer in Delft.

The same year, 1654: I am walking in the narrow alley between the castle of the Crusaders and the busy souk. There are children wild in the alley. There is a bird on the wall. It is him, Carel Fabritius. The bird suggests it (though this bird is a bulbul) but it is the wall that confirms it. Suddenly the gunpowder depot explodes. Fabritius is killed, and most of his paintings are lost to history. But not all is lost. The bridge has been built and it has been crossed, the bridge from shadow into light. He is not yet thirty-three years old.

Brazzaville

There is that which is carried, like a cross. There is that which drapes over, like a funeral sheath. Everywhere, I begin to see as I am carried along by my eyes, are these two energies, which, with water as the third, together begin to constitute an interpretive program: the solid (like wood, iron, or stone), the solid-fluid (clothlike), and the fluid (water). On the banks of the Congo River one afternoon, a boy plays on a railing. He wears a white shirt and black gloves. Ahead of him is the cross on which he is supported, reinterpreted as red elements of iron and painted concrete. On the boy’s body is the infant Christ’s towel, the condemned Christ’s loincloth, the Sudarium of Saint Veronica, the linen shroud of burial: white cloth on a body, the solid-fluid that mediates between the cross and the river. Behind him, the river rushes. Is he a type of Christ, or is he an angel (that glove is as intense and uncanny as a pair of wings), or is he Saint Christopher, the Christ bearer at the river’s lip? But all three are carriers, and types of one another too. Like them, the boy moves between metaphors. Suddenly, he lowers his head, his eyes disappear.

Poughkeepsie

A fluency in the dialect of geography, miniatures, and paper, an inclination for creating a gently fabular atmosphere, a commitment to what seems to be plain description, a return one way or the other to the empty dreamlike classroom, and a testing of the shimmering boundary between the map and the territory are some of the things Elizabeth Bishop, Luigi Ghirri, and Italo Calvino have in common. The empty chalkboard bears the ghostly trace of everything ever written on it. Each soul has its genetics.

Milan

It holds its violence in reserve. It is symmetrical, as are most vertebrates. It is in fact bipedal, like the animal that stands up, the animal that can mourn strangers. This suggestiveness is the key to surrealism. Suddenly coming up for air, a whale breaking the sea’s surface, the surreal object is beyond or over (sur) a reality it might have been expected to stay below. The scissors is a mask without a face.

Berlin

He is masked by the shine. The mask spreads outward. Outside the gilt frame, on the periphery, are various things imperfectly seen: too dark, too small, cut off, blurred. I took this photograph at the moment my friend came down into the lobby. It was the night we were to see the Brahms violin concerto at the Philharmonic. From time to time, people leaned back and closed their eyes, so that Brahms would seep into their bloodstream.

Btouratij

We were a few miles from Tripoli, which is dry, so we stopped by a café to get our last glass of wine. The woman who owned the place was from Iraq, and the café was decorated with postcards and images of Iraq’s ancient history. She brought us white wine. The sun was so bright outside that the road was almost white.

Babel, famous for its tower, became Babylon, in Iraq. On the wall in a café in North Lebanon, Bruegel speaks for Iraq. Bruegel: he painted many things that cannot be painted.

Zürich

I walk around the city not knowing if I am a giant in a miniature landscape or a midget in monumental surroundings. The bright sun obliterates scale. The city is modular: office plans look like city maps, and the façades of buildings resemble street plans. In this fractal city, each fragment is the city in microcosm. Glimmering things—narcotics, stimulants—are stacked and hover just out of reach behind grille and glass. The city is a druggy rush of machine: rectilinear, vertical, tantalizing, and masked. You zoom in and in, and still remain recognizably in the city.

Imagine the city destroyed, and out of one surviving miniature, out of the DNA, say, of a shop front, the city had to be reconstructed—as in Jurassic Park. This is one possible city, the central city. The other is the city of peripheries, which with looser structure also contains the code of the city. Both cities are ever-present in the continuous city.

Berlin

Each brick contains within its form something crushed.

I am on the board of an arts organization. We meet in the organization’s postwar building. The design is beautiful, the rooms large and airy, the whole structure surrounded by a park. For three days we talk about the future. We drink coffee, look at charts, and exchange ideas. I enjoy the intelligence of the curators and my fellow board members. At the end of the third day, the director draws our attention to the past.

On the map of the building we are in, a second map is superimposed: the building that had been there before, before its destruction in the war. (I remember the pain when the doctor cauterized the holes in the retina of my left eye with a laser. An intense pain, not bitter like a knife but sour like darkness.) That first building is constructed in 1872. The banker Hans H. purchases it on an unrecorded date. Charlotte H. inherits the building in 1918, when her husband dies. From 1928 onward, two upper floors are converted into a clinic, for which one Kurt P. is hired as bookkeeper.

Below each map is the ghost of another. Mapping is formalized forgetfulness.

After 1933, the Jewish owner is no longer allowed to operate the clinic. In 1937, Kurt P. purchases the clinic, for a price well below its market value. Charlotte H. has three sons, all of whom flee Germany. Charlotte H. remains, steadily becoming poorer, and in March 1943, she is deported from Berlin to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Her fate there is (un)known.

Berlin

Like speech, which leaves no mark in the air, the arrangement of our bodies leaves no mark in space. A moment later, the man by the trees has moved on. He has not noticed his echo behind him, and the man who echoes him has not noticed him or, even if he has, has certainly not noticed himself noticing him. There are thousands of such echoes and agreements every minute. Almost all go unseen, and almost none are recorded, unless photography intervenes. Berlin is a city of ever-proliferating and overlapping peripheries. But even here there is a code, though it is a code made of wounds.

Copyright © 2017 by Teju Cole. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.