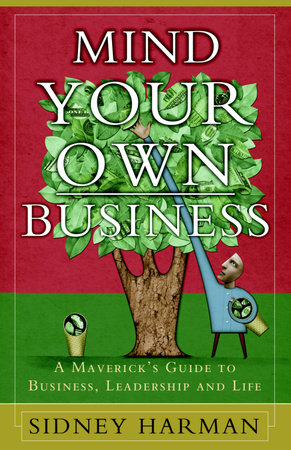

CHAPTER 1

Searching for Solid Ground

The dogmas of the quiet past are inadequate to the stormy present.

The occasion is piled high with difficulty and we must rise to the occasion.

As our case is new, we must think anew and act anew.

-Abraham Lincoln

The Stormy Present

The revelations of corporate misbehavior and financial mischief we've seen recently, and the resulting fervor for reform, should surprise no one.

For decades American business had been in thrall to a pattern of management and development I call, with a nod to Michael Lewis,1 "The Old Old Thing." It was the old school of business, conducted by top-down, authoritative chieftains who were for the most part honest, hardworking, frequently unimaginative but diligent leaders. Its characteristics were long hours, specialists as department managers, and profit as the key to success. It was an American ethnocentric world. Global thinking was rare. Other markets were thought of as export opportunities. Technology played a modest role. It was a simpler world, a more realistic world, unadorned by financial magic. One never read of "proforma profits" offered as a distraction from disappointing real numbers. Cash flow was king. EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization) was buried in footnotes, if it appeared at all. Earnings after interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization were what counted. Debt was scorned. The cash register was an icon.

There were significant exceptions: the crazy days of takeover artists and leveraged buyouts, the rash of wild conglomerates. But for the most part, the old verities held.

Then came the cyclone of cyberspace and dot-com madness-a furious breakaway from the old framework. Business was going global, the old notion of export was disappearing, technology was king, and a new breed of high-flying, very young, jet-setting, gold rush, high-tech gunslingers emerged. The so-called New Economy. The laptop, the cellular telephone, and access were the new icons. Pizza hours became the proxy for old-fashioned hard work, lavish spending the replacement for prudence and savings. The emphasis was on gratification in the present and earnings in the very distant future. The Young Turks were driven by the opium of technology. Globalization was just a first step on the way to the whole universe. With no real grounding, no personal ethic, no moral compass for guidance, New Economy leaders found it all heady stuff.

Of course, there were a substantial number of creative, imaginative, and solidly grounded companies, but the era was surely not dominated by practitioners of the stodgy tried-and-true way.

Many experienced business leaders were confused, challenged, and threatened by the new breed. Fearful that they would be left behind, striving to catch up, to find footing in the larger world and in the presence of the flashy new technology, some jumped ship for new opportunities with dot-com dazzlers; others abandoned the practices that had served business so well for so long. Desperate to generate profits and the elusive but crucial EPS (earnings per share), some yielded to "cooking the books," a poisonous stew.

The Maverick's Way

I have been in business through both periods-for over sixty years. And through those sixty years, I have done it differently.

Let me state up front the principle that has guided me: There is the traditional way to conduct business and do your job, as for the most part it is taught in the business schools and practiced in industry. There is the deeply flawed New Economy way. And there is the maverick's way that looks not to the dogma of the past, nor to existing models of action and behavior, but struggles to determine what is truly effective regardless of traditions and trends. It is a mutant of the Old Old and the New New, a way of thinking that retains the enduring values of the Old and the vigor of the New. One might call it the New Old Thing.

The maverick's way of conducting business forswears the leader as commanding general; it rejects the practice of top-down, authoritative command. Rather, it proposes the leader as catalyst, conscience, and inspirer. It embraces technology, but only in the service of the customer, not to his intimidation or for its own sake. It sees that much of what ails business today arises from the narrowness of preparation, the emphasis on specialization, and the failure to build a philosophical base or sound judgment based on critical thinking. Critical thinking allows one to review business decisions against a carefully developed, carefully honed set of personal values.

When you like or dislike something-a painting, a piece of music, a policy, a point of view, a play, or a business idea-it is useful and rewarding to be able to explain your preference or conclusion, both to yourself and to others. One's evaluations should be based less on "I know what I like" and more on "I like what I know."

Presented with a new advertising campaign, for example, an executive who says "I don't like it" or "It doesn't feel good" may be honest, but this type of comment is not helpful. When you are able to explain your reaction, you will have evaluated and mastered the material and be able to explain why you believe what you believe. For example, "The visual part of this ad does not resonate or harmonize with the text." Or, "The message contradicts our fundamental beliefs," or "The colors are vibrant when the message is intended to be somber."

Developing a reasoned analysis and evaluation that you can communicate to others is the mark of a true leader, a leader who is able to exercise critical judgment rather than one who forces the facts to fit a predetermined conclusion.

You may remember the story of Procrustes (ProKRUStees), a villainous figure in Greek mythology. Not someone you would want to meet, then or now. Travelers on the road to Attica were enticed to stop at his house. Once snared, the victim was tied to Procrustes' bed. Then the poor fellow's legs were stretched or cut off to accommodate the length of the bed-the ultimate "one size fits all." The hero, Theseus, ultimately fitted the villain to his own bed by removing his head.

Over the years, scholars have written extensively of the Procrustean bed and of Procrustean thought-a theory or conclusion forced to fit existing practice or belief. Such thinking encourages the dogma that "this is the way we have always done things." It is the kind of thinking that stifles creativity. Today's equivalent is a failure to "think outside the box."

The leader who sees himself as a catalyst acts in a way that is the very opposite of Procrustean behavior. He may know a great deal about the subject of a meeting, may have more experience and more authority than the others in the group, but he also knows that there is more knowledge and insight available from the group than he or any one person alone can bring to it. The true leader sees his job as setting an environment in which new ideas can emerge that neither he nor any other individual anticipated. That leap of imagination, that moment of genuine creativity, can only be inspired by the leader who encourages exploration and shows a willingness to consider a totally new approach. In doing so, he promotes the growth and development of his associates and, not infrequently, stimulates a truly original solution.

Non-Procrustean leadership sees the relevance to the business of ideas, advancements, and events outside the business, and synthesizes them in an effort to make the company stronger. It requires the ability to accept failure, a willingness to acknowledge what one does not know, and a readiness to yield to a better idea. At Harman International, I liken our executive team to a jazz quartet in which each player is master of his instrument, but subordinates his playing to that of the group. The improvisation and invention that characterize the best jazz quartets arise from the careful listening and response each musician gives to the playing of the others. It is that interaction, inspired and encouraged by the quartet leader, that leads to wonderful, even inspired, music. And so should it be in business.

When the leader is a catalyst, one member, if you will, of the jazz quartet or ensemble, the organization, can change-and a better one can emerge. People have an opportunity to grow and develop, even as hard work and the fundamentals are respected. Meeting one's schedules, financial sobriety, and discipline count, and daring (as opposed to recklessness) is encouraged. Recklessness is acting without consideration of the consequences. Daring, on the other hand, is the conscious decision to go forward after careful consideration of the risks, consequences, and potential rewards. A daring action may or may not work, but it is worth the try. A good leader encourages daring action, and does not penalize it when it fails.

I do not know Bill Gates-I have never met him-and I disagree with some of the tenets of his company. But I respect the fact that he is daring and impressively nimble. I define nimbleness as the willingness to challenge orthodoxy, to question dogma, reject the counsel that "this is the way we've always done it," and to move quickly to implement a new vision. Bill Gates is clearly nimble. He turned the Microsoft leviathan around on a dime when he concluded that the cyberworld was exploding and that the future of his company could not be written entirely in the Windows operating system. His thinking is far removed from that of Procrustes.

Warren Buffett, whom I know and admire, refused to follow the lemmings onto the Net and over the cliff because it did not feel right to him. He just didn't get it. Even as Gates, after careful consideration, determined to chart a new direction for Microsoft, Buffett, after equal consideration, decided against engaging the dot-com world. Though these two friends reached very different conclusions, the process of evaluation, judgment, and action was the same. Certainly each was daring in his own way.

An Act of Daring

My first act of daring, I would say, was joining Bernard Kardon in 1953 to create Harman/Kardon. I quit a well-paying job to start a business in a very new field. A year later we had created the first integrated, high-fidelity audio receiver. Conventional wisdom had it that you could not create high fidelity without using separate components: a tuner to receive radio signals, a preamplifier to enhance and enlarge them, and a power amplifier to deliver the enhanced signals to separate loudspeakers. Yet the advantages of a complete, integrated, all-in-one receiver seemed manifest to us. It would be simpler to install and simpler to operate. Because the separate components were combined on a single chassis, the risks of electrical interference and hum would be significantly reduced. So while a high-end receiver flouted conventional wisdom, it made good sense to us. In 1955 we took another major step when I judged that the world of single-channel, monaural sound was coming to an end and that the new world of stereophonic sound was about to emerge. Virtually overnight we abandoned a carefully developed new monophonic product line and created a totally new series of stereo amplifiers-the very first in the industry. They were ready just in time for the 1955 trade show. That decision triggered a huge success and gave us an initial lead over the competition that lasted for years. Decades later, driven by similar daring, Harman International moved early and decisively from products based in the analog domain to products centered in the developing digital domain.

As a result of that decision, we were compelled to seek, excite, and attract a large number of digital engineers. I felt that our way of running a company fit especially well with the new technology. But I was equally certain that we must not subordinate intelligent management and marketing to the technology. Technology must never be permitted to tyrannize. It must be the servant of the client. That lesson is ignored at great peril. Many catastrophic business decisions have arisen from the view that the engineers know best; if a new product could be built, that was reason enough to go forward. In my experience, it is not reason enough. The Mazda talking car of some years ago, for example, affronted the people to whom it gave instructions. It was a complete failure. The endless number of self-proclaimed ultimate convergence products for the home, intended to combine all the functions of a computer with those of home entertainment, ignored the way in which people live, and prefer to live. The technology has been in existence for decades to permit the video telephone. Yet people have made clear that they are discomfited when they are observed while on the phone. There is welcome refuge in the telephone's visual anonymity. Similarly, it has taken years for otherwise confident people to overcome their terror at attempting to program a VCR. For many, the flashing 12:00 on the digital readout continues to be a symbol of frustration. Happily, new technology incorporating a hard disk in the home TV recorder does the tough work quietly and invisibly.

Business School Thinking

Business and the business schools have for too long lionized the specialist, the person who has learned how to do one thing and do it well, but who, as a consequence, has almost no idea how the whole enterprise works. Time and again, in small companies and large, I have encountered senior executives who live lives of silent terror. They do their jobs, and they believe that they do them effectively, but they do not have a clue about how the whole enterprise works. It seems to them that the company has a life and motion of its own, and they live in fear that they will somehow be found out. That kind of departmentalized thinking-the specialist in the silo-produces paralysis and an absence of innovation and creativity. Coupled with top-down autocratic command, it is the essence of what I think of as old analog management. It can bring a company's growth to a full stop.

I say, "Get me some poets as managers." Poets are our original systems thinkers. They contemplate the world in which we live and feel obliged to interpret, and give expression to it in a way that makes the reader understand how that world turns. Poets, those unheralded systems thinkers, are our true digital thinkers. It is from their midst that I believe we will draw tomorrow's new business leaders.

Many senior executives, I am sure, decide at some point that they wish to be surrounded by people of similar training, similar aptitude and attitude, similar interests, and similar style to their own. But it is a luxury that, in the real world, rarely exists. Life and business do not work that way. No matter who you are, no matter the company and no matter what its history, in large measure you must play the hand you are dealt. You find people at the company when you arrive, and you promote people as shifts occur. If you were working with a blank slate, many of them would not be the people you would choose to hire or promote. But we rarely work with a blank slate. A leader's job is to lead, to teach and to help shape, to inspire teamwork much as the best baseball managers and football and basketball coaches promote team spirit by galvanizing the players they have been dealt and honing them into a winning organization.

Copyright © 2003 by Sidney Harman. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.