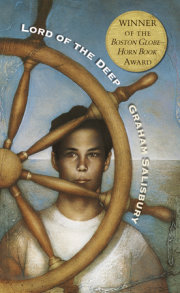

1Honolulu,August 1941The Spirit of JapanI'd be lying if I said I wasn't afraid."Bad, bad times," Pop mumbled just yesterday, scowling to himself in the boatyard while reading the Japanese newspaper, Hawaii Hochi. He mashed his lips together and tossed the paper into the trash. I pulled it out when he wasn't looking. Some haole businessmen were saying all Japanese in Hawaii should be confined to the island of Molokai. Those white guys thought there were too many of us now; we were becoming too powerful. The tension outside Japanese camp in Honolulu was so tight you could almost hear it snapping in the air.And to make things worse, Japan, Pop's homeland, was stirring up big trouble.In 1931, when I was six, the Japanese invaded Manchuria, and they had been pushing deeper into China ever since. Less than a year ago, they'd signed up with Germany and Italy to form the Axis, all of them looking for more land, more power. Then, just last month, Japan flooded into Cambodia and Thailand.And my homeland, the U.S.A., was getting angry.President Roosevelt was negotiating with Japan to stop its invasions and get out of China, but nothing seemed to be working.And for every American of Japanese ancestry, Pop was right--these were bad, bad times.That summer I'd just turned sixteen. Me and my younger brother, Herbie, who was thirteen, helped Pop build boats in his boatyard, a business he'd had since he and Ma came to Hawaii from Hiroshima in 1921. Pop had been making sampan-style fishing boats all his life. He had a skilled apprentice named Bunichi, fresh off the boat from Japan by two years. With all of us helping out, Pop's business managed to survive.We were finishing up a new forty-footer for a haole from Kaneohe, the first boat Pop had ever made for a white guy. And there would be more, because Pop's reputation had grown beyond Japanese camp. Without question, there was no better boatbuilder in these islands than Koji Okubo, my pop. We'd been working on this one for more than seven months now, ten hours a day, six days a week. I was painting the hull bright white over primed wood soaked in boiled linseed oil. I had to strain the paint through fine netting so it would go on like silk, leaving no room for the smallest mistake. Pop lived in the Japanese way of dame oshi, which meant everything had to be perfect.The paint fumes were getting to me, so I climbed down off the ladder to go out back for some fresh air. A small, flea-infested mutt got up and followed me into the sun. I'd found him a couple of months ago licking oil off old engine parts in the boatyard, and I'd given him some of my lunch. Now that ratty dog stuck to me like glue. I called him Sharky because he growled and showed teeth to everyone but me. Pop didn't like him, but he let him live at the shop to chase away nighttime prowlers.Pop's shop was right on the water, and just as I walked outside, a Japanese destroyer was heading out of Honolulu Harbor, passing by so close I could hit it with a slingshot. A long line of motionless and orderly guys in white uniforms stood on deck gazing back at the island. I squinted, studying them as Sharky settled by my feet. Pop suddenly ghosted up next to me, wiping his hands on a paint rag. I could see him in the corner of my eye. He was forty-eight years old and starting to get a bouncy stomach. A couple inches shorter than me, about five three. His undershirt was white and clean, tucked into khaki pants that hung on him like drying laundry, bunched at his waist with a piece of rope. He had short gray hair that prickled up on his tan head. As usual, he was scowling.Sharky got up and moved away. Pop pointed his chin toward the destroyer. "That's something, ah?" he said in Japanese. "Look at all those fine young men." They looked proud, all right."To them," Pop went on, unusually talkative, "the Emperor is like a god. They would be grateful to die for him."Grateful to die? Pop's eyes brightened. "The spirit of Satsuma," he said. "That's what lives in those boys--the unbeatable fighting spirit of Satsuma."He nodded in admiration, then continued on over to the lumber pile to look for something.What Pop said gave me the willies, because he wanted me and Herbie to be just like those navy guys, all full up with the national spirit of Japan, Yamato Damashii. Pop kept a cigar box of cash savings hidden somewhere in the house, money to send us back to Tokyo or Hiroshima to learn about our heritage. "You are Japanese," he would say. "How can you learn about your culture and tradition if you don't go to Japan?"Sure, but what if I got there and war came because the U.S. and Japan couldn't work things out? What if I got trapped and dragged into the Japanese army--or navy, like those guys on that ship? What would I do then? Because I sure didn't feel that kind of spirit. I wasn't a Japan Japanese. I was an American. Pop's newspaper had said that people around Honolulu were worried they had a "Japanese problem" on their hands--us. What would Japanese Americans do if Japan and the U.S. went to war? Where would our loyalties lie?It was ridiculous, because there was nothing to worry about.

Copyright © 2005 by Graham Salisbury. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.