Walker / THE PATRIARCH

1

Benoît Courrèges, chief of police of the small French town of St. Denis and known to everyone as Bruno, had been looking forward to this day so much that he’d never considered the possibility that it might end in tragedy. The prospect of meeting his boyhood hero, of being invited into his home and shaking the hand of one of France’s most illustrious sons, had awed him. And Bruno was not easily awed.

Bruno had followed the career of the Patriarch since as a boy he had first read of his exploits in a much-thumbed copy of Paris Match in a dentist’s waiting room. He had devoured the article and dreamed of starting a scrapbook on his newfound hero but had no money for the magazines and newspapers he would require. The young Bruno made do instead with libraries, first at his church orphanage and later, when he’d been taken into the stormy, child-filled household of his aunt, at the public library in Bergerac. The images had remained in his head: his hero silhouetted against camouflaged fighter planes in the snow, wearing shorts and a heavy sidearm in some desert, drinking toasts in one ornate palace or grand salon after another. His favorite was the one that showed the Patriarch as pilot, his helmet just removed and his hair tousled, waving from his cockpit to a cheering crowd of mechanics and airmen after he’d become the first Frenchman to break the sound barrier.

Bruno could not help but smile at his own excitement. His boyhood was long behind him, and he knew grown men should not feel like this. Bruno had worn a military uniform himself, knew the chaos of orders and counterorders and all the messy friction of war. He knew, as only a veteran can, that the public image of the Patriarch must conceal flaws, fiascoes and botched operations. He should have grown out of this hero worship, or at least appeased it now that he had been able to call up old newsreels and TV interviews on his computer. But some stubborn, glowing core remained of that boyhood devotion he had felt for a man he thought of as France’s last hero.

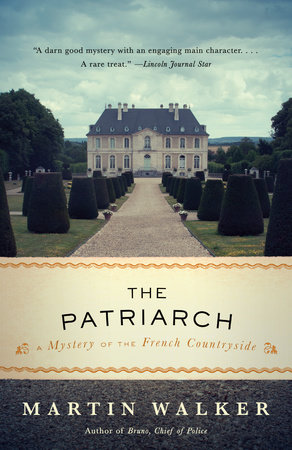

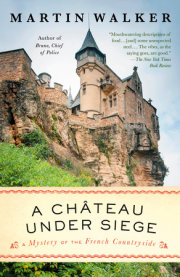

As he waited in the receiving line to shake his hero’s hand, Bruno knew that he’d never attended an event so lavish nor so exclusive. The château was not large, just three floors and four sets of windows on each side of the imposing double doors of the entrance. But its proportions were perfect, and it had been lovingly restored. While the adjoining tower with its stubby battlements was medieval, the château embodied the discreet elegance of the eighteenth century. The string quartet on the balcony overlooking the formal garden was playing the “Fall” movement from Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, a piece that perfectly suited the surroundings. Bruno could imagine the Fragonard paintings of perfectly posed maidens that should grace its rooms; he knew they had been painted at around the same time as some pre-Revolution nobleman had transformed his ancestors’ fortress into a comfortable home.

Below the balcony, at least a hundred people were sipping champagne as they chatted and strolled in the garden. The sound of women’s laughter made a perfect backdrop to the music. On the broad terrace to which Bruno was restricted by the wheelchair he steered, at least as many guests again were mingling, taking glasses from the trays offered by the waiters dressed in air-force uniforms. He heard snatches of conversations in English, German, Russian and Arabic and picked out at least a dozen different national uniforms. He recognized politicians from Paris, Toulouse and Bordeaux, mostly conservatives, but with a scattering of Socialist mayors and ministers from the government in Paris.

Whenever Bruno spotted them gathering in their usual partisan clumps, they always seemed to defer to a stunningly attractive blond woman whom Bruno had just met, the Patriarch’s daughter-in-law, Madeleine, who was acting as hostess. She had given Bruno only a cool smile of welcome while shaking his hand perfunctorily in a way that moved him on to her husband, next in the receiving line.

Beyond the formal garden of the château, the fields to the right sloped gently away to the Dordogne River and the grazing Charolais cattle upon them looking as if they had been carefully posed in place. To the left, between two ridges that were covered in trees turning gold and red, one of the lazy curves of the Vézère River glinted in the autumnal sun. Even the weather, Bruno thought, would not dare to spoil the ninetieth birthday of such a distinguished son of France.

“This must be one of the finest views in the country,” the Red Countess said from her wheelchair. “Our own view is pretty good, but that church spire on one side of the river and the ruined castle on the other give this one something that is almost perfection. Marco bought it for a song, you know. I was with him when he first saw this place and decided to buy it. I think it helped that my own château was close by.” She paused, smiling. “Marco was one of my happier affairs. It lasted longer than most.”

“Where did you meet him?” asked Marie-Françoise, the countess’s American-born heiress. Just out of her teens, she was looking fresh and enchanting in a simple dress of heavy blue silk that matched her eyes. Her French, once halting but improved by private coaching and by her time at the university of Bordeaux, was now fluent.

“I met him in Moscow, where he was a star. It was the Kremlin reception after Stalin’s funeral, and Marco looked magnificent in full-dress uniform. Everybody knew him, of course. Our ambassador was put out that Marco was given precedence over him. Khrushchev came up to embrace him. Apparently they’d met somewhere on the Ukrainian front after the Battle of Stalingrad.”

She looked up at her great-granddaughter and gave a gleeful smile that made her look younger than her years. “I’ll never forget those frosty glances from the other women present when Marco came up to give me his arm. Mon Dieu, he was a handsome beast. He still is, in his way.”

Bruno followed her gaze to the double doors leading into the château where the man known across France as the Patriarch was still receiving his guests. He stood erect in his beautifully cut suit of navy blue, the red of his tie matching the discreet silk in his lapel that marked him as one of the Légion d’Honneur. His back was as straight as a ruler, and his thick white hair fell in curls onto his collar. His jaw was still as firm as his handshake, and his sharp brown eyes missed nothing. They had looked curiously at Bruno as he’d first appeared, pushing the wheelchair. But once Bruno was introduced by the Red Countess as the local policeman who had saved her life, the Patriarch’s eyes had crinkled into warm appreciation.

“That is the magic of this woman,” the old man had said in the voice of a much-younger man, and he bent to kiss her hand. “She always finds a knight-errant when she needs one.”

Colonel Jean-Marc Desaix, the Patriarch, had been honored as a war hero in two countries, with the Grand Cross of the Légion d’Honneur and the gold star and red ribbon of a Hero of the Soviet Union. The first had been presented by his friend Charles de Gaulle and the second by Stalin himself at a glittering ceremony in the Kremlin.

Like most French boys, Bruno knew that the Normandie-Niemen squadron of French pilots flying Soviet-built Yak fighters had shot down more enemy aircraft than any other French unit. It had been the second-highest-scoring squadron in all the Russian air force, shooting down 273 enemy planes. Twenty-two of these had been downed by Marco, then a dashing and handsome young man whose bold good looks were featured constantly in the Soviet newsreels and newspapers. As people heard of his exploits over the BBC, Marco became a hero at a time when France had sore need of such warriors.

Marco had qualified as a fighter pilot in the first days of May 1940, just as the Second French Cavalry Division was trotting through the wooded trails of the Ardennes to repel what they thought was a German reconnaissance force. What they encountered was the Seventh Panzer Division, led by General Erwin Rommel, whose tanks brushed the French cavalry aside and launched an assault that would take them to the English Channel in less than two weeks. Marco saw no action in France. The day after getting his wings, he was posted to the French colony of Syria, flying one of the underpowered Morane-Saulnier fighters that had proved so inferior to the German Messerschmitts in the battle for France. In 1941, when the British invaded and occupied Syria to prevent the Luftwaffe from using its air bases, Marco was one of more than five thousand French servicemen who volunteered to join de Gaulle.

It was while Marco was retraining on British Spitfires that de Gaulle persuaded Stalin to accept a squadron of French pilots to serve on the eastern front, where the German panzers were closing in on the Volga River and on Stalingrad. Marco traded in his desert shorts for winter clothing and joined the squadron of French volunteers on the long train journey north through Persia and the Caucasus. As the defenders of Stalingrad held out, Marco and his colleagues were retraining on Yakovlev fighters. And just after the besieged and frozen remnants of the German army under Field Marshal von Paulus surrendered, the Normandie squadron was declared operational.

Bruno had read it all. As a boy, he’d thrilled to the exotic Syria, tried to imagine the long train journey from desert heat to Russian cold, and to the present day he remembered that the French fighters shot down their first enemy, a Focke-Wulf fighter, on the fifth of April 1943. By the end of the summer, they had shot down seventy more, and only six of the pilots were still alive. But they had won more than just their dogfights. The Nazi field marshal Wilhelm Keitel had ordered that any captured French pilot should be shot out of hand, rebels and traitors to their Vichy-run homeland, and their families in France should be arrested and dispatched to concentration camps.

Bruno had vowed to become a pilot, like his hero, until an overworked teacher in his overcrowded school told him brusquely that his poor scores in math and physics ruled out any prospect of being accepted by the French air force. As the next best thing, before his seventeenth birthday Bruno volunteered to join the French army.

Marco Desaix had returned to France in 1945, leading the flight of forty Yak fighters that Stalin had decided the Normandie-Niemen pilots could fly home to join the reborn French air force. Then in 1948, with discreet official backing, Marco volunteered to fly for the infant state of Israel. He found himself flying a Messerschmitt fighter donated by the Czech government and became an ace all over again. Back in France afterward, he joined Dassault Aviation as a test pilot and became the first French pilot to break the sound barrier. Marco then helped Dassault sell its Mystère and Mirage jet fighters to become the core of the new Israeli air force and launched his next career as a businessman, becoming a director of Dassault and later of Air France and Airbus. Finally, in tribute to a long and patriotic career, he had been elected to the Senate. It was an epic life that Bruno knew by heart. Bruno felt he would be attending the party of the year in Périgord. He suspected he’d not been invited on his own account but as the escort to the Red Countess, as a man who could be relied on to manage a wheelchair and its fragile passenger.

Copyright © 2015 by Martin Walker. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.