Mountain View

From your car, Mountain View is not a terrible-looking place. Nothing at all like the Alcatraz/Sing Sing notion of prison--that cold, gray, isolated rock--we all mostly carry around in our movie-glutted imaginations. Set against rolling hills, the Mountain View unit of the Texas Department of Corrections (TDC) comprises low red-brick one-story buildings, sidewalks, trees, flower beds; the grass is tended. Texas and American flags fly side by side.

Not that you want to move in. Double chain-link-and-barbed-wire fences mark the unit maximum security; armed-guard towers steal the breath and--even though you know in advance they're bound to be there--chill the heart. Driving down Texas State Highway 36 that day, mainly I was thinking how grateful I was not to be locked up in there. What trees there are are small: scrub oaks, mesquite, scrawny cottonwoods. Prisons aren't built in lush landscapes. As one correctional officer told me, "I don't know whether TDC chooses the worst places in the world to build on or if they just get that way.

East across Highway 36 from Mountain View--from which raw, craggy hills but no mountain can be seen--is the less restrictive Gatesville Unit. Only one row of chain link and barbed wire over there.

Guards on horseback carrying rifles at the ready rode down through the hills to my right, watching over the single file of a work squad, all men, marching in. The inmates wore stark white. The guards were in gray. Lunchtime; in prison parlance, chow.

On the way to Gatesville from my home, a drive of some two and a half hours, I had been alternating tapes of Maria Callas and Aaron Neville. In the shadow of the penitentiary, I switched the music off.

Although the morning had been cool, as the day wore on the temperature climbed fast, the way it can in Texas in early March. In this part of the state, the sun, once it gets its strength up, gives no mercy. I had my windows up, the air conditioning on. In the course of driving to Gatesville, I had stripped off my jacket, then my sweater, and was down to wide-legged pants and a cotton blouse.

What am I doing here? I kept asking myself this question. I am fifty years old, a fiction writer; I could be home in my nest of an office, making stuff up. What am I doing here?

Answers flitted by; cheap, glib notions, nothing I trusted. Don't ask made more sense. Don't figure it. Just go.

In my rearview mirror, as guards on horseback watched for traffic, the work squad filed across the highway. On the phone the warden had been cordial, her directions explicit, and so I had no problem finding Mountain View. I had an hour to spare. At the intersection of new Highway 36 with the old business route, I turned right. The entrance to Mountain View was right there. Men repairing the road in front of it looked up, waved. I waved back, turned my car around, and took Business Route 36 to downtown Gatesville.

When I mentioned to friends that I was considering making this trip, they all disapproved. I tried to explain, I was not out to spring Karla Faye Tucker or even to save her life. Karla's imprisonment was not a railroad job; on the witness stand she had admitted having participated in two unspeakably hideous murders. She did what they said she did.

"But look at her," I said to my skeptical friends. And I showed them the newspaper picture.

Friends only glanced at the photograph. I knew what they were thinking: if I needed a cause, there were plenty of far more deserving people out there to feel sorry for. Without exactly saying so, friends encouraged me to drop this new idea. They meant well. Having seen me through bad times, now that I seemed to be on my feet again they didn't want me to slide back into the dark. Eventually I solved the problem. I didn't show the picture anymore. My feelings, however, did not change. I was captivated by her, that's all. Her looks, her story, the extremes to which passion, circumstance, and drugs had taken her.

Almost three years had passed between the time I first saw the newspaper story and March 9, 1989, when I put the Callas and Neville tapes in my car and finally went.

You can find a town like Gatesville anywhere in Texas--county seat, built on a square, courthouse in the middle, around it stores, a pool hall, title company, cafe serving a steam-table all-you-can-eat noon meal. The Coryell County Courthouse is as fancied up as a wedding cake, but the stores and businesses surrounding it are plain and flat-fronted, with a strained grit-free look, as if having been scrubbed within an inch of their life by wind, sun, and the Protestant--mostly Baptist--work ethic. In a rock building which used to be a lumberyard there is a county museum, closed except on weekends. The museum is run by a historical society, mostly made up of ladies with time, energy, and intelligence to spare.

I stopped at a grocery store for lunch--diet Coke and Fritos--then took Business Route 36 back out to the prison. A couple of miles out are the No Hitchhiking and Do Not Pick Up Hitchhikers signs that mark the boundaries of state prison property. To my right was the Gatesville Unit. Ahead was Mountain View.

I slowed down.

Everyone who visits a prison says the same thing. "I knew how it was going to be. I'd seen the movies. I'd psyched myself up. Still . . ."

It must have to do with dream recall, the nightmare reality of being locked up, the terrifying notion of how easy it might be to trip over the line into lawlessness and, then, the place beyond the fences. Or with not wanting to see--prisons, prisoners--and not wanting, once they're locked up, to have to think about those people anymore.

Along the road to my right, chain-link fence topped by six-strand barbed wire stretched ahead to the intersection. Guard towers interrupted the fencing every fifty yards or so. A guard in one tower sat with his feet propped on a desk and a portable telephone in his hand. In the next one, the guard stood gazing out at the prison yard and down across the road.

I wondered if they were calling ahead tower to tower to report the location of my car. There was no reason to think they had; I was driving slowly, keeping to my lane, obeying every rule. It just seemed such a lonely job up there. Punch in, punch out. No radio, no newspaper, no pal to chat with. Only the wind, the sun, the endless parade of inmates, the telephone, that gun. Lacking reason, mightn't a guard eventually make up some excuse to fire it--for something to do?

The picture of Karla Faye in the

Houston Chronicle had been a page-one close-up color head shot, remarkably clear for a newspaper photograph, Karla Faye at twenty-six. Mostly what you saw at first were her dark eyes, that tumbling mane of hair. Unfold the newspaper and out came the rest of her, a pretty young woman in prison whites, head slightly tilted, left hand cupping her chin. I didn't know who she was then, of course, although I vaguely remembered the trial, one of those daily horror stories you hate to read and can't get enough of. Mostly, like everyone else, I remembered the weapon and some splashy comments she'd made about sex.

Long face, high cheekbones, black hair (an escaped curl created a single parenthesis around her left eye), soft smile, a chipped tooth. At the very center of her dark brown eyes the camera flash had left its mark, a pinpoint white dot. Like a doorway to her thoughts, the dot made her look vulnerable.

Next to the photograph was the headline ON DEATH ROW, PICKAX MURDERER FINDS A "NEW LIFE."

In the spring of 1986, I read the Chronicle story, read the sidebar, turned back to the picture, studied it, reread the story: a young woman on Death Row, the rock-and-roll life that had got her there; the gruesome crime with its nightmare weapon, thing of grade-B horror films; her hot sexual comments and subsequent jailhouse rehabilitation.

Karla Faye Tucker made page one some two years after her death sentence for a number of reasons. For one thing, the fact that, however our thinking has shifted, when a woman kills it's still news.

A lot more women commit crimes now. More women sell drugs, rob, steal, burgle, sell their children, go to prison. But men are the ones who commit the violent crimes, at a rate of almost nine to one, therefore it is men who receive death sentences, men who sit out their lives warehoused on various Death Rows, waiting to die or not. In Texas in the spring of 1990, there were four women on Death Row in Gatesville, 287 men in Ellis I Unit in Huntsville. In the country, there were a total of 2,185 Death Row inmates, only 25 of whom were women. Between 1976 and 1992, 166 men had been executed but only one woman, Velma Barfield in North Carolina.

Karla Faye makes for good copy also because she's a paradox. She's attractive, she's photogenic, she knows how to pose; her crime is unthinkable yet she has confessed to it, and now she has this look of sweetness, this spontaneity, this look of being altogether present for the camera, no secrets. You read Karla's life story, you look at her picture, you think, if things had been different. . . . It makes you want to believe that people change, that confession helps, that there is hope.

She looks so serene. The state I was in at the time, I envied her. I wondered if you had to go to jail to get calm again.

For the Chronicle photograph, Karla had cupped her chin in her hand and tilted her head--not into the hand but slightly away from it. Her chin rests in the meat of her palm, her ring and little finger cover a part of her lower face, her slim fingers extend from her jawline to her earlobe. Her nails are long and carefully tended, she is wearing a gold watch and a ring, and she is looking into the camera without--it seems--a twitch of restraint or unease. In the caption she is quoted as saying she is happy. She looks happy. She looks--we don't speak this way anymore, but the word that came to mind the first time I saw the photograph was "good." And yet this same person had confessed to having committed acts that might well be called--if we talked that way anymore--evil.

The sidebar to the main story was entitled "The Embodiment of Evil?" Down in the story, one of the men who prosecuted Karla's case is quoted as saying that when he first saw Karla in 1983, just after she was arrested, he didn't want to turn his back on her. "Her attitude and the way she looked and everything about her was the personification of evil.''

Trying to imagine this attractive young woman as evil incarnate, I read the story again and again. I thought I might like to write about a girl whose life had made such swings, from darkness to hope. More than write about her, I wanted to meet her. Just lay eyes on her.

That was in 1986. Friends said, "Don't do it," and I didn't. I trusted them. And that was proper. It was right to wait.

After reading the story one last time--the murders of course were unthinkable; women don't get the death penalty for fathomable crimes--I put the paper on the floor by my office chair, where I file things I'm not finished with. A few days later I read the story again. The same prosecutor who in 1983 thought Karla Faye Tucker was the personification of evil was now saying she was a brand-new, caring person, intelligent, helpful, getting her high school diploma, taking college correspondence courses, reading everything in sight and almost gushy, "like a puppy." Prosecutors, prison officials, policemen--people who routinely refuse to go behind a jury when it recommends the death penalty--were making a case for lifting the sentence in her case. "The person who is Karla Tucker today," said one, "is not the same person who was Karla Tucker at that time."

Did I believe that? I did not. People don't become other people.

"I like her," said another. "And I hope she doesn't die."

J.C. Mosier, a homicide detective who had worked on the case, was not sure what to think. "I don't want to see her die," he states, then he catches himself. "I believe in the death penalty," he explains, "and she's not the only person that I've ever sent to Death Row. But in most cases, they're bad people, period. She never had a chance from the start. There was no way for her to go but bad. . . . When it comes down to seeing someone die, I don't think I would like that."

Okay, I told myself, so let it go. You don't want to get involved with another young person who will die.

Peter had been dead since September 1984, the victim of an unsolved hit-and-run. There was a time, not that long prior to the appearance of Karla's page-one picture, when I had lain on the couch for days, not changing clothes, hardly lifting my head, just lying there, a person who felt she no longer had edges to define her, who felt more like a cracked and spilled raw egg than a person, a person gone from the world as she knew it. Adrift from time itself, I considered madness a reasonable option in those days: one more snapped thread and I'd be there.

By the spring of 1986 I knew I was better. With the help of time, friends, family, a psychiatrist, a bereaved-parents support group, books, poems, Mozart, a palm reader, and a psychic, I had made my way to a bearable state of mild depression and chronic disappointment. And so I meant to listen to the voice of reason, to pay attention to my friends. I meant to be cautious, to take care.

I set the story about Karla Tucker aside. I did not, however, throw it away; I simply folded it and laid it on a desk I use for storage. Other papers were piled on top. Occasionally I cleaned them off. When I got to the bottom, there Karla Faye was again, chipped tooth, chin cupped, that look. I would stand in my office alone and just look at her.

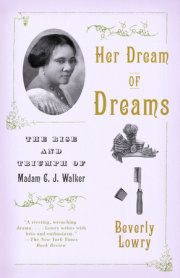

Copyright © 2002 by Beverly Lowry. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.