9780307959454|excerpt

Doerries / THEATER OF WAR

Learning Through Suffering

I

In the fall of fourth grade, I landed a small role in a production of Euripides’ Medea at the local community college in Newport News, Virginia, where my father taught experimental psychology. I played one of the ill-fated boys slaughtered at the hand of their pathologically jealous mother. I can still remember my one line, which I belted backstage with abandon as several drama majors pretended to bludgeon me with long wooden canes behind a black velvet curtain—“No, no, the sword is falling!” The director, a short, fiery German auteur with spiky white hair and a black leather jacket always draped over his shoulders like a cape, would scream at the cast during rehearsals at the top of his lungs until we delivered our lines with the appropriate zeal. Whenever our performances reached the desired fever pitch, he would jump up from his chair and explode with delight, “Now veeee are koooooking!”

During daytime performances for local high school students, the boredom in the theater was as palpable as the thick layer of humidity generated by sweaty adolescents fidgeting in their seats, whispering and blowing spitballs in the shadows, waiting for the agony to end. Whenever I entered the stage, wearing a tight gold polyester tunic, which clung to my thighs and itched mercilessly under the unforgiving lights, I heard rippling waves of laughter move through the crowd. What’s so funny? I wondered, squinting into the stage lights. After the show closed, at the cast party, one of my fellow actors confirmed that the laughter had, in fact, been at my expense. Unaccustomed to wearing a tunic, I had provided the high school audiences with an extended, full frontal view of my underwear while perched atop a large granite boulder. Seeing my Fruit of the Looms was likely the most memorable event in those students’ mandatory encounter with Euripides.

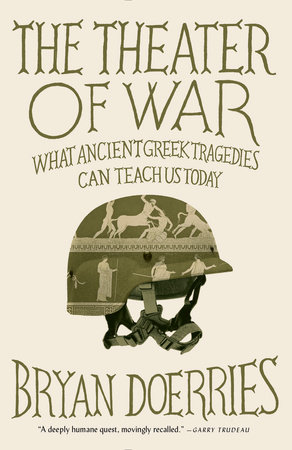

Most of us probably developed an allergy to ancient Greek drama in high school, when some well-intending English teacher required us to read plays like Oedipus the King, Antigone, Prometheus Bound, and The Oresteia in rigid Victorian translation, or forced us to watch seemingly endless films featuring British actors in loose-fitting sheets and golden sandals declaiming the vocative refrain “O, Zeus!” from behind masks. If your early encounters with the ancient Greeks zapped you of any ambition to ever pick up a play by Aeschylus, Sophocles, or Euripides again, you are not alone. Aeschylus is known for having written in his play Agamemnon that humans “learn through suffering,” but for most students, studying ancient Greek drama is just an exercise in suffering, with no apparent educational value.

Ironically, some scholars now suggest that attending the dramatic festivals in ancient Greece and watching plays by the great tragic poets served as an important rite of passage for late-adolescent males, known as ephebes. It is for this reason, according to the argument, that so many of the tragedies feature teenage characters—such as Antigone, Pentheus, Neoptolemus, and Orestes—thrust into ethically fraught situations with no easy answers and in which someone is likely to die. According to this understanding, tragedy may have been viewed as formalized training, preparing late adolescents for the ethical and emotional challenges of adult life, including military service and civic participation. In other words, the very plays that were designed thousands of years ago to educate and engage teenagers, to help transform them from children into productive citizens, have managed to bore them senseless for centuries.

One hope of this book is to administer an antidote to the obligatory high school unit on ancient Greek tragedy.

The first thing you learn in school about tragedy is that it tells the story of a good and prosperous individual who is brought to ruin by some defect in his or her character. This traditional reading of Greek tragedy goes something like this: Blinded by pride, or hubris, Oedipus ignores the warning of an oracle, unwittingly murders his father and sleeps with his mother, and—though he manages to save the people of Thebes from the bloodthirsty Sphinx—ultimately turns out to be the contagion that is plaguing his city. Conclusion: Oedipus was a great but flawed individual who was deluded by power and crushed by external forces beyond his grasp. We love stories about well-intentioned, flawed characters, because they make the most compelling drama. Also, as Aristotle pointed out, we take no pleasure in watching morally flawless people suffer.

But the ancient Greek word commonly translated in textbooks as “flaw,” hamartia, more accurately means “error,” from the verb hamartano, “to miss the mark.” Centuries later, by the time of the New Testament, the same word—hamartia—came to mean “sin,” fully loaded with all its moral judgment. In other words, tragedies depict characters making mistakes, rather than inherent flaws in character. I know that I miss the mark hundreds of times each day. I often have to lose my way in order to find the right path forward. Making mistakes, even habitually and unknowingly, is central to what it means to be human. Characters in Greek tragedies stray, err, and get lost. They are no more flawed than the rest of humanity; the difference lies in the scale of their mistakes, which inevitably cost lives and ruin generations.

At the same time, being human and making mistakes—even in ignorance—does not absolve these tragic characters of responsibility for their actions. Had they fully understood what they were doing, they most certainly wouldn’t have done it. But they did it all the same. It is in this gray zone—at the thin border between ignorance and responsibility—that ancient Greek tragedies play out. This is one of the many reasons that tragedies still speak to us with undiminished force today. We all live in that gray zone, in which we are neither condemned by nor absolved of our mistakes.

What is so utterly flawed about the idea of the “tragic flaw” is that it encourages us to judge rather than to empathize with characters like Oedipus. Tragedies are designed not to teach us morals but rather to validate our moral distress at living in a universe in which many of our actions and choices are influenced by external powers far beyond our comprehension—such as luck, fate, chance, governments, families, politics, and genetics. In this universe, we are dimly aware, at best, of the sum total of our habits and mistakes, until we have unwittingly destroyed those we love or brought about our own destruction.

It is not our job to judge the characters in Greek tragedies—to focus on their “flaws.” Tragedy challenges us to see ourselves in the way its characters stray from the path, and to open our eyes to the bad habits we may have formed or to the mistakes we have yet to make. Contrary to what you may have learned in school, tragedies are not designed to fill us with pessimism and dread about the futility of human existence or our relative powerlessness in a world beyond our grasp. They are designed to help us see the impending disaster on the horizon, so that we may correct course and narrowly avoid it. Above all, the flaw in our thinking about tragedy is that we look for meaning where there is none to be found. Tragedies don’t mean anything. They do something.

Another concept that gets drilled into our heads in high school is “fate.” The word for fate in ancient Greek—moira—means “portion.” In Greek antiquity, Fate was worshipped in the form of three goddesses: Clotho, the “spinner”; Lachesis, the “allotter”; and Atropos, the “unturnable.” Fate was older and more powerful than all the gods combined, and the entire cosmos was subject to its laws. No one lived above it or beyond it. Yet the Greek concept of fate, as it is encountered in Greek tragedy, is much subtler than many of us generally understand. In tragedy, the concept of fate is not mutually exclusive of the existence of free will; nor does the ancient idea of “destiny” negate the role of personal choice and human agency. In fact, as in the case of Oedipus, human choices and actions are required in order to fulfill an individual’s fate or destiny.

In 1976, the year I was born, my father was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, an insidious, cruel disease that dismantled his mind and body slowly, almost imperceptibly, over a period of thirty-three years. In spite of the diagnosis, he adamantly refused to adjust his lifestyle, though he knew this choice would eventually come at a deadly cost. The nerves in his feet died first. Then the bones in his ankles collapsed. Then came the incurable lesions, the festering sores, the bouts of colitis, the kidney failure, the daily dialysis treatments, the kidney transplant, the septic infections, the endocarditis, the blindness, the dementia, the seizures, the horrifying hallucinations, and finally—after much suffering—a protracted, terrifying death, during which he believed a gaggle of black, ravenlike demons were swarming all around him, waiting to take his soul to hell.

The word diabetes comes from the Greek verb diabaino, “to run through.” The name derives from the signature symptoms of the disease, an unquenchable thirst combined with a constant need to urinate. Water “runs through” diabetics. The condition results from a deficiency in the pancreas, which normally produces insulin, a hormone that regulates sugar levels in the blood. Without enough insulin, sugars run wild, causing, among other symptoms, extreme thirst while steadily choking off the blood supply to nerves and tissues. Ultimately, over decades, the disease leaves no organ unscathed.

Type 2 diabetes is a fitting metaphor for the human condition as portrayed in ancient Greek tragedy, and for the interdependence of human action and fate. Those who are diagnosed with the disease often possess a genetic predisposition to develop it. It is written into their DNA, like an ancient intergenerational curse. And yet what diabetics choose to do with the knowledge of their condition has a direct impact upon their lives, and upon those who love them. Thus, in spite of the “curse” of their disease, diabetics still play a role in shaping their destiny. How they behave and the choices they make help determine the course their lives will take. Many are able to control their blood sugars through a combination of drugs, diet, and exercise, extending their life spans and delaying the progression of the disease for decades. But as many as 60 percent of type 2 diabetics do not adhere to the recommendations of their doctors or faithfully take their medication. This is primarily because diabetics do not experience the negative effects of eating junk food, not exercising, and allowing blood sugars to fluctuate for years. It is also because the medical regimen for most full-blown diabetics involves daily injections of insulin and constant monitoring of sugars with needle pricks to well-worn fingertips.

Fate refers to the cards we were dealt, the portion we were given at birth. Tragedy depicts how our choices and actions shape our destiny. No one ever said that change was easy, but my father believed it was impossible. He often told his experimental psychology students that when it comes to human behavior, what passes for change is no more than a fantasy, an illusion. This was his long-formed, heavily entrenched conviction, based on years of research, working with human beings and rats.

Nothing infuriated me more than to listen to him rationalize his own self-destruction with this specious argument. His unwillingness to acknowledge even the remote possibility of meaningful change fueled some of our worst fights and forever drove a wedge between us.

In the heat of one memorable argument, he eyed the collection of Sophocles’ plays I had under my arm and asked, “Don’t you believe in fate, Bryan? All those Greek plays end in disaster, no matter what the characters try to do.”

Like Oedipus, my father was adopted, but he wasn’t told until much later, so he spent the entirety of his childhood believing that his adoptive parents were his biological parents. And like Oedipus, he discovered who his biological parents were near the end of his life, when it was too late to act upon this knowledge and avert his own self-destruction. In Sophocles’ version of the Oedipus myth, a Corinthian man, in a moment of inebriated indiscretion, accuses Oedipus of being a bastard, planting the seed that, decades later, bears fruit in the horrifying realization of his true identity. When my father turned sixteen, it was his grandmother, Hattie, who took him aside and casually, one might say cruelly, shattered his world by telling him he was adopted.

Decades later, while searching for a viable kidney donor for my father, we found out who his biological parents were. As fate would have it, they both worked at the Catholic hospital in Fairhaven, New Jersey, where he had been born. My father’s father had been his pediatrician, a Spanish immigrant, who had indulged in an extramarital affair with a Puerto Rican nurse. My father’s adoptive parents, who were in their forties and had been unable to conceive, were more than willing to help the physician and the nurse sweep their dalliance under the rug by taking the baby off their hands. Had it not been for my great-grandmother’s loose lips, they might have perpetuated the myth that he was their son for the rest of their lives.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Hispanic Americans are at a “particularly high risk for type 2 diabetes.” My father’s fate, as it turned out, was something he could have, at the very least, deferred, had he investigated the identity of his biological parents. But like Oedipus, he did not really want to know the truth until it was too late. When Oedipus discovers who his parents were, he gouges out his eyes with golden pins from his mother’s gown and stumbles off into the desert to die. My father drank a chocolate milk shake and slipped off into sugar-induced oblivion.

A week before my father died, frail and demented, at the age of sixty-six, I flew down from New York City to visit him at a nursing home in Virginia, a few blocks from where I had grown up. I brought him a chocolate milk shake from Monty’s Penguin, the local diner we had frequented during my childhood. Though neither of us wanted to say goodbye, we both knew it was the last time we would see each other. After a long day of reminiscing and grappling with unanswerable questions, we eventually ran out of things to say.

The sun had already set, though I hadn’t noticed its absence until after the room faded to black and the floodlights outside poured through cracks in the blinds, crisscrossing the floor. We sat in the darkness for an indeterminate time and looked at each other with understanding and regret. Finally, after my father closed his eyes and slipped back into semiconsciousness, I tossed my coat over my shoulder and slowly approached his bed, bending over to look at him one last time, to take in his face, so I wouldn’t somehow forget its contours after he was gone.

Suddenly, without opening his eyes, he reached up and grabbed my arm, pulling me toward his face—contorted in a rictus of horror—with the desperation of a drowning victim. Clamping down with all his remaining strength, he sobbed: “The same thing is going to happen to you, and to your brother! It’s fate. It’s fate!”

It’s his dementia talking, I told myself, not him. But it was also a curse.

As a child, I often spent afternoons observing him train his advanced psychology students in a small laboratory a few blocks from our house. Among the many wonders of that mysterious windowless space was a floor-to-ceiling polygraph machine, a shriveled human brain floating in a glass jar of formaldehyde, and rows of metal cages packed with albino lab rats, peeking between bars with beady red eyes. In one experiment, which I observed at perhaps too young an age to fully understand, he demonstrated how rats would eventually give up their will to live if provided enough negative reinforcement, through a series of seemingly indiscriminate electrical shocks. Eventually, when they’d had enough, the rats stopped struggling, rested their heads on the floors of their cages, opened their mouths, and simply waited to die.

Now, as I left the nursing home and rushed to my car, with my father’s last words still echoing in my ears, it occurred to me that the curse of his interpretation of fate was that it permitted him to act like those rats. Did he somehow expect me to do the same? Was this the lesson he wanted me to learn from tragedy?

For my father, fate was a pretext to behave fatalistically. It was the same notion of “inescapable fate” that I had encountered in school. Whenever I heard it, every cell in my body rose up in revolt, resisting the idea that we humans live without the ability to change the course of our destinies. Thinking about the way my father placed the concept of fate at the center of his self-destructive, pessimistic worldview, I couldn’t help believing that the objective of ancient Greek tragedy—and its grim depiction of humanity—was radically different from what we have imagined for thousands of years.

Fate and free will are not mutually exclusive in ancient Greek tragedy. Fate always requires human action—or inaction—in order to be fulfilled. Perhaps by cultivating a heightened awareness of the forces that shape our lives and of the pivotal role our choices and actions play in realizing our destiny, Greek tragedy was designed to promote the possibility of change. In other words, the fate that awaited Oedipus was avoidable, as was my father’s. So is yours, and so is mine.

II

Although I first encountered Greek tragedy in elementary school, it wasn’t until my first year at Kenyon, a small liberal arts college in rural Ohio with a rich literary history, that I became interested in the classical world, for all the wrong reasons.

The classicist and philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche once wrote:

1. A young man cannot have the slightest conception of what the Greeks and Romans were.

2. He doesn’t know whether he is fitted to investigate them.

In his 1874 essay We Philologists, a wry polemic against nineteenth-century German classicism, Nietz-sche argues that young students are poorly suited to study the ancients precisely because they lack the life experience to understand the motivations and struggles of other humans, let alone those who lived more than two thousand years before them. Even worse off than students in this regard, suggests Nietzsche, are career academics.

“The philologist,” he writes, “must first of all be a man.” Philologist in Greek means “lover of words,” and for centuries the term has denoted the profession of studying ancient languages and cultures. Nietzsche argues, tongue firmly planted in his cheek, “Old men are well suited to be philologists if they were not such during the portion of their lives which was richest in experiences.” In other words, only those who have lived the extremities of life—who have loved, traveled, risked, lost, and suffered—can extract anything of value from reading the ancients. Conversely, he suggests, studying philology can get in the way of living a full, rich life. “In short,” he concludes, with a playful jab at his critics, “ninety-nine philologists out of a hundred should not be philologists at all.” At the core of Nietzsche’s argument lies the concept that experience is a prerequisite for understanding the ancient world.

At age eighteen, with relatively little life experience, I signed up for two semesters of ancient Greek, in a class that met for several hours a day, Monday through Friday, and set out to prove to myself that I had what it took to investigate the Greeks. The four other students in my class and I convened daily around a large, stately oak table on the first floor of a neo-Gothic building, complete with gargoyles and soaring stained-glass windows. On the first day of class, the legendary professor Bill McCulloh, a former Rhodes scholar from Ohio and then chair of the classics department, passed around a short survey that included the question “Why are you interested in studying ancient Greek?”

My response, in retrospect, was embarrassingly naïve: “In pursuit of esoteric knowledge.” I somehow envisioned ancient Greek to be an initiation, a rigorous course of study that would provide access to a hidden world, such as the Eleusinian Mysteries, famously secret rites and ceremonies held each year in honor of the goddesses Demeter and Persephone. Nietzsche was right. I hadn’t the slightest clue as to who the Greeks and Romans were. But I possessed a burning desire to find out.

Copyright © 2015 by Bryan Doerries. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.