Chapter 1

The Founding Fathers and Modern America

"What happened to my America?”

“Why don’t those people speak English?”

And “Mr. Williams, don’t take this the wrong way, but . . . you know, at the donut shop, at the gas station, in the schoolyard--have you ever seen so many immigrants, especially the Latinos everywhere?”

“These kids are so thuggish. . . . Do you see any reason to be confident in this country’s future?”

After the 2012 presidential election I heard those kinds of urgent questions from older white conservatives. They seemed disoriented. With obvious anxiety they felt the cycle of history spinning away from them, leaving them dizzy and angry at being pushed away from the center of politics and culture by the emerging “New America.”

One poll found 53 percent of white Americans saying the changes in culture, economics, demographics, and politics were coming too quickly and damaging America’s “character and values.”

This sense of disillusionment is not limited to older white conservatives. In the same 2011 poll, done by Heartland Monitor, the National Journal, and Allstate, 51 percent of African Americans said they too felt all the demographic and political churning was too much and the “trends are troubling.”

A 2015 poll done by Reuters and Ipsos found that 62 percent of Republicans, 53 percent of Independents, and 37 percent of Democrats “feel like a stranger in [their] own country.” Another 72 percent of Republicans, 58 percent of Independents, and 45 percent of Democrats “don’t identify with what America has become.”

I myself am hardly immune from this national anxiety over change, and it hit me personally eight years before the 2012 election, in 2004. That year I turned fifty and felt the new realities of life pushing against me everywhere.

Just think about how much the world changed during my first fifty years on Earth.

When I was born, in 1954, people who looked like me sat at the back of the bus, drank out of separate water fountains, and went to separate schools. Eighty-nine years after the end of the Civil War, my father, an immigrant black man, could not get anything but a low-end job in most American companies. He could not go to most American schools, could not live in most American neighborhoods, and was not allowed to swim in most pools, golf on most courses, or go to most amusement parks.

My mother, who was born in Panama, did not see Latinos as a major force in American life. The census did not even bother to count the number of Latinos in the United States during the 1950s. In 1970 Latinos in the United States added up to less than 5 percent of the population. Today Latinos make up over 17 percent of the U.S. population, outnumbering blacks as the largest minority group.

In 1954 abortion was not a critical political issue. The idea of women controlling the rights to their own fertility and their bodies was not a “culture war” argument splitting conservatives and liberals. Fifty years ago U.S. government policy, supported by conservatives, promoted family planning. It was seen as a boon to parents, allowing them to better provide for a smaller number of children.

In the 1950s there was no controversy over homosexuality, largely because society was not willing to have the conversation. My mom had a gay male friend who came by the apartment regularly to design and sew dresses. Yet I never heard him or anyone else talk about gay rights. Gays remained in the closet for fear of persecution.

What a different America I saw in 2004. The leaps in the nation’s demographics, economy, and culture made it feel to me like hundreds of years had passed.

America went from allowing smoking everywhere to banning smoking everywhere. Gambling went from the street corner “numbers man” to government-run lotteries. The rising presence and influence of women in corporate America, the military, and the media shifted the power equation between the sexes, as more women decided they did not need a man to support themselves, to live a full life, or even to have a child. In fact, women began to outnumber men in colleges and graduate schools. They became the majority of the workforce as male-dominated blue-collar jobs went to Asia. Conversations about gay rights morphed into court cases about the right of gays to have legal, state-approved marriages.

Essential fibers of the social fabric--public schools, for example--began to fray, leading to calls for reform (charter schools, magnet schools, and vouchers) that would allow parents and students greater choice to find the best school for their needs. America experienced its first major gun control movement, saw the rise of a national gun lobby, and endured a spike in mass shootings in schools around the country.

And there was wholesale change in the federal government in the decades following World War II. We saw postwar America become the global “arsenal of democracy” that President Franklin D. Roosevelt had promised it would back in 1940, protecting far-flung regions of the world from Soviet communism. We witnessed the South become a Republican stronghold. That led to a conservative political revolution that culminated in the presidency of Ronald Reagan.

New technology emerged, changing the way Americans communicate, process information, and form relationships. It seemed that within just a few years suddenly everyone had a cell phone. New cable television channels, hundreds of them, appeared in everyone’s home. Internet and podcast programming moved entertainment to new platforms. And today we can use apps such as OkCupid and Tinder to find people to date in our local area.

The economy got hot in 2004, thanks to revolutions in finance, high-tech companies, hedge fund investments, and ever-higher housing prices. The bubble, of course, would soon burst.

As the economic ways of the past unraveled early in the twenty-first century, the white working class, though buoyed for a while by rising home prices and cheap credit, has faced a rude reality of stagnant wages due to a dim job market, an end to pensions, and the decline of unions. The same has been true for African Americans. Despite the rise of the black middle class in the 1970s, after the 2008 recession the African American unemployment rate soared as high as it had been in the 1960s. In 2005, Hurricane Katrina blew the cover off ingrained black poverty in New Orleans, exposing nationwide roots of black poverty tied to record high rates of unwed mothers and failing schools. The big racial arguments of the latter half of the twentieth century, which had focused on the continuing impact of the history of segregation and the need for affirmative action in college admission and hiring, faded. The focus on black poverty shifted to questions about family structure. And at the same time, ironically, the promise of equality under the law had come ever closer to being fully realized for educated blacks, Latinos, and Asians. That is why immigrants kept coming to America in waves. Change was hitting the country from multiple directions.

During these years I traveled the country as part of a National Public Radio (NPR) series called The Changing Face of America. The shows examined issues ranging from the increased use of personal technology on a daily basis to changes in how Americans worshiped to the increased acceptance of legal, state-supported gambling across the country. For the series I met with Mexican immigrants who had been given amnesty under President Reagan’s 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act. I talked with the first generation of Americans who grew up using cell phones and the Internet after the 1996 Telecommunications Act. I reported on poor people, especially young minorities, who lost the right to welfare support because of the welfare-to-work laws crafted by Republican House Speaker Newt Gingrich and President Clinton in the 1990s.

Looking back, it seems that the folks I met through The Changing Face of America were living out the theories of Buckminster Fuller and Ray Kurzweil, two futurists who have argued that because of exponential leaps in technology and our understanding of biology, change is coming at a faster rate now than ever before in human history. Kurzweil calls it the “law of accelerating returns.” In a 2001 essay he wrote, “We won’t experience 100 years of progress in the 21st century--it will be more like 20,000 years of progress (at today’s rate).”

So how long ago and far away is the America of 1776? How distant is the Founding Fathers’ America from the reality of twenty-first-century America? I can only imagine how different the people I met while working on that show would be if I reconnected with them today. Imagine the dizziness the Founding Fathers would experience.

The NPR series won critical acclaim. These stories of change in American life from east to west, from urban to rural, and among young and old reminded me that American life was being transformed in exponential leaps. As a journalist, I was particularly alert to the new reality of fragmented politics and niche media. Experiences that at one time served to unify large segments of the population, such as watching one of the three network evening news programs, began to dissolve, with audiences for news programs breaking into politically separate groups, listening to their preferred views on talk radio or watching politically tilted cable news shows.

Even the surge of American nationalism following the 9/11 attacks and the decision to go into two wars faded quickly. At first flags flew everywhere and people stood to applaud the troops at sporting events. But as time passed the wars didn’t feel so real anymore. No one was drafted. College campus protests like those that emerged in opposition to the war in Vietnam never took place because the professional force fighting the war and dying generally did not come from elite colleges--or colleges at all, for that matter.

Similarly, the once widespread trust in institutions began to slide. The public schools suffered because of poor performance, the Catholic Church because of pedophile scandals. Baseball stars found themselves before Congress, accused of cheating with performance-enhancing steroids. Our confidence in the goodwill of Wall Street bankers and other financial leaders eroded. Trust in the word of government officials fell when people found out they had been misled about the presence of weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, and later when the government was shown to be have been asleep at the switch when the economic crash came in 2008.

As a black man, I was particularly struck that the once reliable framework of racial identity in America--white majority and black minority dealing with the aftermath of slavery and legal segregation--began to blur as Latinos and Asians began to exercise new cultural and economic influence on the nation.

For the next few years I continued filing away stories that fit the pattern of these foundational shifts in American life. I wanted to weave this collection of colorful threads into a vivid tapestry that revealed the new look of modern American life.

What became clear to me was that America was engaged in a new beginning. This was not the country where I grew up. America has been reborn any number of times over the course of its existence. The westward expansion, the Civil War, the New Deal--all had their turn at reinventing the country. Here, at the beginning of the twenty-first century, I found myself looking at one of those extraordinary moments of national transformation. A new America had emerged, at times painfully bursting from past realities and shedding cultural norms, as it entered stage after stage of uncertain change.

To me, this radical transformation was something to celebrate. Yes, political polarization and fear of rapid change were making people anxious. But overall, middle-class Americans continued to enjoy a high standard of living compared to other people around the globe. Plus the policies that forced people of color and women into subservience have all but vanished. And we Americans have a chance to create, like artists with an untouched canvas, a new, potentially better reality for ourselves.

Then, in 2010, I had an epiphany that forced me to look deeper at the radical changes taking place in the structure of the country. It began with that year’s U.S. census report--an unlikely starting point for an epiphany. The census results on the age of the American people jumped out at me. They showed that over a quarter of the American population was younger than the age of eighteen.

At first I didn’t believe it. But the census graphs indicated that children, high school age or younger, made up the largest single cohort of any of the demographic categories. I had thought people my age, baby boomers, accounted for the lion’s share of the population. I had believed that the declining birth rate among whites should be shrinking the number of young people. But the census told a different story. The influx of immigrants with sky-high birth rates had created an incredibly young nation with a total population of over 300 million American citizens.

I remember expressing my shock at the young age of the population to friends and fellow journalists and having them react with surprise at my surprise. “Have you gone to the movies lately?” one fellow journalist asked. “Every other movie is about vampires or zombie hunters. Whom do you think they’re being marketed to? They’re not making movies for you and me, buddy. They’re made for those young people.” My wife asked me if I had gone to the mall lately. The businesses that were bustling, even during the recession, she informed me, sold clothing and accessories to young people--stores like J.Crew, H&M, and Urban Outfitters. To my embarrassment, she told me that I’d have a hard time buying a pair of jeans. The newer denim styles are designed to fit tight young bodies, she said with laughter; older people have to shop for “comfort” jeans. And, she added, it’s obvious that merchants understand how family life is changing. Busy moms no longer take charge of buying clothes for their teenage children. Instead, parents give money to their children and let them go to the mall.

It occurred to me that to be a good journalist early in the twenty-first century I needed to better understand young Americans. I wasn’t totally in the dark. I did know that younger voters, especially first-time voters, constituted a crucial part of the coalition that elected Barack Obama in 2008. According to exit polls, Obama carried two-thirds of the youth vote against Republican John McCain--about 15 million ballots. Both Obama’s supporters and his critics described him as a “rock star” because of his ability to connect with younger votes who had previously been written off by politicians as too lazy and disengaged to show up at the polls on election day. Obama attracted thousands of them at a time to his rallies and enthralled them, surrounding himself with the kind of adoration you’d sooner associate with Taylor Swift. But I also had a hunch that America’s youth-heavy population had affected more than Obama’s 2008 victory. I needed to meet with these young people and listen to them to hear in their own words how they see their role in this new American story. The rising social and economic power of young people was intersecting with their growing political power.

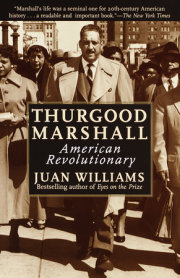

Copyright © 2016 by Juan Williams. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.