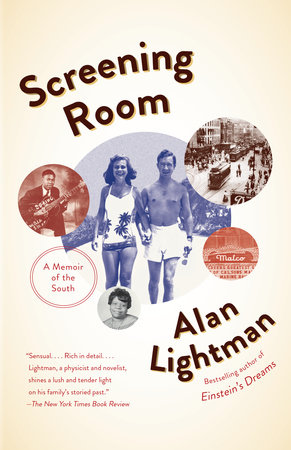

Rememberings 1955. A lady’s pink boa flutters and slips through the air. All down the street, Negro janitors shuffle behind white horse-drawn floats and scoop up piles of manure. I am carried along by the heave of the crowd, the smell of the popcorn and hot dogs with chili, the red-faced men sweating dark rings through their costumes, the Egyptian headdresses, the warble of trombones and drums of the big bands from New York and Palm Beach—me six years old wearing a tiny white suit with white tie clutching the hand of my six-year-old date, both of us Pages in the grand court, trailing the Ladies-in-Waiting gorgeously dressed in their gowns made of cotton, the white gold of Memphis. Cotton town high on a bluff. Boogie town rim of the South.

Far off through colored balloons, I glimpse the King and Queen, just off their barge on the muddy brown river. They solemnly stride through an arch made of cotton bales. Bleary-eyed women and men reel in the streets, drunk from their parties and clubs. From an open hotel window, someone is playing the blues. Music flushes the cheeks of the coeds and debutantes, dozens of beauties from the Ladies of the Realm who flutter their eyelashes at the young men. I am lost in this sea, miraculously picked from a first-grade school lottery; candy and glass crunch under my feet, wave after wave of marching youth bands flow through the street. Then a young majorette hurls her baton high in the air. Before it can fall back to earth, the twirling stick touches the trolley wires and explodes in a burst of electrical fire. Pieces of baton rain on the heads of the crowd.

Summons to Memphis It began with a death in the family. My Uncle Ed, the most debonair of the clan, a popular guest of the Gentile social clubs despite being Jewish, had succumbed at age ninety-five with a half glass of Johnnie Walker on his bedside table. I came down to Memphis for the funeral.

July 12. Midnight. We sit sweating on Aunt Rosalie’s screened porch beneath a revolving brass fan, the temperature still nearly ninety. For the first time in decades, all the living cousins and nephews and uncles and aunts have been rounded up and thrown together. But only a handful of us remain awake now, dull from the alcohol and the heat, sleepily staring at the curve of lights that wander from the porch through the sweltering gardens to the pool. The sweet smell of honeysuckle floats in the air. Somewhere, in a back room of the house, a Diana Krall song softly plays.

I wipe my moist face with a cocktail napkin, then let my head droop against my chair as I listen to Cousin Lennie hold forth. Now in her mid-eighties, Lennie first scandalized the family in the 1940s when, in the midst of her junior year at Sophie Newcomb, she ran off to Paris with a man. Since then, even during her various marriages, she has occasionally disappeared for weeks at a time.

“With due respect to the dead,” Lennie whispers to me, “Edward trampled your father. Always.” She pours herself another bourbon and stirs the ice with her finger. “When he was about fifteen years old, your Uncle Ed opened a bicycle shop. He got some tools, read a magazine article, and started repairing his friends’ bikes. Charged them their allowance money. Your dad begged Edward to let him work in the shop. At first, Edward refused. This, of course, made Dick even more desperate to help; he was dying to work in that shop. Finally, Edward agreed, but he charged Dickie money every week for the privilege.”

“Shush,” says Rosalie.

“Did you know how your grandfather M.A.’s heart attack

really happened?” Lennie says to me, smiling slyly and sipping her bourbon.

“What do you mean?”

“Exertion,

bien sur. The best kind. And not with your grandmother.”

Forty years ago, I escaped Memphis, embarrassed by the widespread belief that southerners were ignorant bigots, and slow. I returned only for brief visits. Now I’m back again, for an entire month, caught by things deep in me I want to understand.

Lennie lights a new cigarette and wriggles her stocking-covered toes, poised to let fly another story. Cousins nudge forward in their reclining chairs. In my mind, I am sitting at the breakfast table with my grandfather, watching with delight as he butters my silver-dollar pancakes, then lathers on grape jelly and honey, finally sprinkling sugar on the entire concoction. Sweet as pecan pie. Muddy like the Mississippi River. Fragments of visions of Cotton Carnival. Elvis. Malco. BBQ at the Rendezvous. Someone moans from the pool, the next generation, and Lennie exhales a cool cloud of blue smoke.

Copyright © 2015 by Alan Lightman. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.