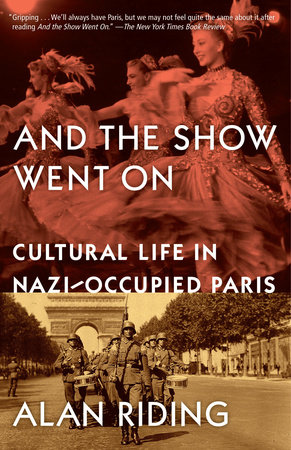

· c h a p t e r 1 ·

Everyone on Stage

ON JUNE 14, 1940, the German army drove into Paris unopposed. Within weeks, the remnants of French democracy were quietly buried and the Third Reich settled in for an indefinite occupation of France. Who was to blame? With the country on its knees, many in France now saw this as a defeat foretold, a debacle that had been in the making since France emerged from World War I, victorious in name but shattered in spirit. In the bloody and muddy trenches of theWestern Front, 1.4 million Frenchmen died, representing 3.5 percent of the population and almost 10 percent of working-age men. Further, the 1 million Frenchmen who were left badly maimed, those ever-present

mutilés de guerre, made it impossible to forget the past. With France already alarmed by its low prewar birthrate, this slaughter ofmen and future fathers meant that it was not until 1931 that the country exceeded its 1911 population of 41.4 million—and, even then, this was in large part thanks to immigration.

At the same time, the country was being let down by its political class. The Third Republic, founded in 1870 after France’s defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, was plagued by instability and consumed by political bickering. Although the economy fared relatively well in the 1920s, postwar reconstruction lagged far behind. Then, in the 1930s, confronted by the twin threats of the Great Depression and the spread of extremist ideologies across Europe, France’s rulers chose to ignore both. In a country that had long boasted the originality of its political ideas, a string of dysfunctional governments eroded public faith in democracy and boosted the appeal of the Nazi, Fascist and Communist alternatives. Most critically, with the Great War spawning a nation of pacifists, the French preferred to ignore mounting evidence that the country would soon again be at war with Germany. And when war became inevitable, they chose to believe official propaganda boasting that their army was invincible. This monumental self-delusion only compounded the shock at what followed. When Hitler’s army swept across western Europe in the spring of 1940, French defenses crumbled in a matter of weeks. Neither 1870 nor 1914 had been this bad.

Yet even in the deepening gloom of the interwar years, as artistic and intellectual freedoms were being extinguished across Europe, Paris continued to shine as a cultural beacon. The majority of Parisians were poor, but they had long since been evicted from the elegant heart of Paris by Baron Haussmann’s drastic urban redesign a half century earlier. This “new” Paris was the favored arena of elitist divertimento, drawing minor royalty, aristocrats and millionaires to buy art, to race their horses in the Bois de Boulogne, to hear Richard Strauss conduct

Der Rosenkavalier at the Paris Opera, to party in the latest Chanel and Schiaparelli designs.

Painters, writers, musicians and dancers also flocked there from across Europe and the Americas, in some cases seeking sexual freedom, in others fleeing dictatorships, in many hoping for inspiration and recognition. Embracing everything from the literary solemnity of the Académie Française through the avant-garde of Surrealism to the high kicks of the Moulin Rouge, Paris offered both enlightenment and entertainment. And wandering across its pages and stages like eloquent courtesans were intellectuals, artists and performers. Whether admired for their ideas, their imagination or simply their Bohemian lifestyle, they enjoyed the trappings of a privileged caste. “The prestige of the writer was something peculiarly French, I believe,” the astute essayist Jean Guéhenno later wrote. “In no other country of the world was the writer treated with such reverence by the people. Each bourgeois family might fear that its son would become an artist, but the French bourgeoisie as a group was in agreement in giving the artist and the writer an almost sacred preeminence.” Put differently, culture had become inseparable from France’s very image of itself. And the rest of Europe recognized this. But with the swastika now flying over Paris, how would French culture— its artists, writers and intellectuals, as well as its great institutions— respond? Again, the answer lay in the turmoil of the interwar years.

Nowhere was French cultural leadership greater than in the visual arts. Between the Franco-Prussian War and World War I alone, art movements born in France— Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Les Nabis, Fauvism and Cubism— succeeded one another in what came to resemble a permanent revolution. The 1914–18 conflict did little to disrupt this. While German artists like Otto Dix, George Grosz and Max Beckmann addressed the nightmare of trench warfare, artists in France paid little heed to a war being fought barely a hundred miles north of Paris. When it was over, those nineteenth-century giants Renoir, Monet and Rodin were still alive, while the influence of Pablo Picasso, Marcel Duchamp and Henri Matisse continued to grow. Many artists with prewar reputations, men like Georges Braque, André Derain, Maurice de Vlaminck, Kees van Dongen, Pierre Bonnard and Aristide Maillol, also remained faithful to their prewar styles. Fernand Léger was a rare exception. After he spent two years on the front, his art was transformed, with his sketches of artillery and planes anticipating his tubular “mechanical” paintings of the 1920s. Bonnard avoided the trenches, serving briefly as a war artist and painting just one scene of desolation,

Un Village en ruines près du Ham. But he quickly returned to his cherished themes of nudes and interior scenes.

For European artists, Paris was the place to meet great artists and to aspire to become great oneself. And it helped that the city was an important art market. From the late 1890s, the legendary dealer Ambroise Vollard carried the names of Cézanne, Gauguin and Van Gogh abroad and, in 1901, he gave Picasso his first exhibition in Paris. In the interwar years, it was the turn of other dealers, notably Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler and the Rosenberg brothers, Léonce and Paul, to keep European and American collectors supplied with the new art from Paris. For foreign artists, the city’s energy, bubbling away in the studios and cafés of the Left Bank, was as appealing as any specific art movement. True, Salvador Dalí, Max Ernst, Man Ray and Joan Miró embraced Surrealism, but other foreigners went their own ways, among them Constantin Brancusi, Chaïm Soutine, Piet Mondrian, Amedeo Modigliani and Alberto Giacometti. The list of prominent French artists in Paris at that time was even longer. And to these could be added the architects and designers who created Art Deco as a style that would define the 1930s. Probably at no time since the Italian Renaissance had one city boasted such a remarkable concentration of artistic brilliance.

In the performing arts, change came from abroad, with Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes leading a revolution in dance that would influence ballet for much of the twentieth century. In 1912, the troupe’s star dancer, Vaslav Nijinsky, shocked Paris with his erotic interpretation of Claude Debussy’s

Prélude à l’après- midi d’un faune. The following year, the dancer was at the center of a riot in the Théâtre des Champs- Élysées during the premiere of Igor Stravinsky’s

Rite of Spring, when some spectators mutinied against Nijinsky’s unorthodox choreography and the music’s disturbingly primitive rhythm.

Diaghilev’s role as a promoter and organizer of talent was still more important. Among choreographers, he recruited Michel Fokine, already a major figure in Russian dance, and he made the names of Léonide Massine, Bronislava Nijinska (the dancer’s sister) and George Balanchine. Among dancers, along with the inimitable Nijinsky, he turned the English-born Alicia Markova and the Russians Tamara Karsavina and Serge Lifar into international stars (Lifar later also ran the Paris Opera Ballet). A strong believer in the “total art” that Wagner had called

Gesamtkunstwerk, Diaghilev also pulled different art forms together as never before. He invited Derain, Rouault and Picasso, as well as the Russian artists Léon Bakst and Alexandre Benois, to design his stage sets. And while his favorite composer was Stravinsky, who also wrote

The Firebird,

Petrouchka,

Les Noces and

Apollo for the company, Diaghilev commissioned ballets from Sergei Prokofiev, Maurice Ravel, Darius Milhaud, Francis Poulenc and Strauss. One memorable example of “total art” was

Parade, a ballet that was conceived by the artist-poet Jean Cocteau and combined music by Erik Satie, choreography by Massine, scenario by Cocteau himself, set, curtain and costumes by Picasso and program notes by Guillaume Apollinaire. First performed at the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris on May 18, 1917, it, too, caused a scandal.

Diaghilev never returned to Russia. By the time of his death, in 1929, other Russian artists and writers— among them the painters Marc Chagall and Natalia Goncharova— had fled the Bolshevik Revolution for the safety of Paris. After Hitler took power in 1933, it was the turn of more artists and intellectuals, many of them Jews, to seek refuge in France; these included the abstract painter Wassily Kandinsky and the composer Arnold Schönberg, as well as the writers Joseph Roth, Hannah Arendt and Walter Benjamin.

Other foreigners found a different kind of liberty in Paris. When the novelist Edith Wharton settled in France shortly before World War I, the experimental writer Gertrude Stein was already receiving the likes of Picasso and Matisse in her Left Bank apartment at 27 rue de Fleurus, where she lived with her lesbian partner, Alice B. Toklas. In the 1920s and1930s, Stein became a kind of eccentric matron to the “lost generation” of American writers, notably Ernest Hemingway, Thornton Wilder, John Dos Passos, Ezra Pound and F. Scott Fitzgerald. Henry Miller moved in a different— and more impecunious— circle, but he, too, enjoyed a freedom that, he later noted, “I never knew in America.” Little wonder, since three of his 1930s novels,

Tropic of Cancer,

Black Spring and

Tropic of Capricorn, were banned in the United States as obscene. One gathering point for both American and French writers was Shakespeare & Company, the Left Bank bookstore that Sylvia Beach had opened at 12 rue de l’Odéon, across the street from La Maison des Amis des Livres, run by her friend and lover, Adrienne Monnier. Beach also came to the rescue of James Joyce, who had moved to Paris in 1920; with American and British publishers shying away from Joyce, fearing charges of obscenity, she dared to publish his monumental

Ulysses in 1922. In the late 1930s, Samuel Beckett followed Joyce to Paris, equally determined to escape the suffocating strictures of deeply Catholic Ireland. Their relationship became strained only when Joyce’s troubled daughter, Lucia, fell for Beckett— and Beckett did not reciprocate.

Josephine Baker, the black American dancer and singer, was another who flourished in the artistic melting pot of interwar Paris. Happy to escape racial discrimination in the United States, she arrived in Paris in 1925 to perform

La Revue nègre at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées with a black American dance troupe; almost immediately, she was hired away by Les Folies Bergère. There, she became a star, winning over Parisians with her erotic and funny cabaret shows, which included her love song to Paris, “J’ai deux amours, mon pays et Paris,” and her trademark “Danse sauvage” performed bare breasted and wearing just a skirt of artificial bananas. Soon she was also exploiting her exotic image in French movies like

Zou- Zou and

Princesse Tam Tam, where she played a Tunisian shepherdess–turned–Parisian princess in true Pygmalion style. In 1934, she even sang the title role in Offenbach’s operetta

La Créole. It helped that, at a time when the French were becoming increasingly xenophobic, black American culture was all the rage in Paris. Above all, jazz and swing brought by black Americans was enthusiastically adopted by French musicians, none more brilliant than the Gypsy guitarist Django Reinhardt and his Hot Club de France. La Baker, as she was known, was not the only cabaret diva. Music halls and cabarets were by far the most popular entertainment in Paris and, by the time Édith Piaf joined Josephine on the scene in 1935, Léo Marjane and particularly Mistinguett— La Miss— had long been queens of the night. Press speculation that La Miss and La Baker were feuding only helped to pull in the crowds. Male crooners like Maurice Chevalier and Tino Rossi and bandleaders like Ray Ventura were no less admired.

Copyright © 2011 by Alan Riding. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.