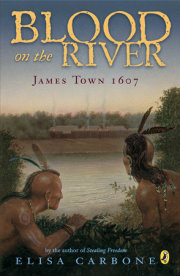

ONE

It’s things we ran away from that got us here, and now there’s no place farther out to run except the wide, rolling Atlantic Ocean.

December 27, 1895

Dripping. That’s what got my attention first. Cold water dripping right on my face while I was trying to sleep, two nights after Christmas and just four days after Grandpa and I had climbed up on the roof and done what we’d thought was a good patching job. Dripping, and the wind whistling through the cabin like it was a harmonica, then the sound of Daddy crashing in through the door, and the smell of burning fish oil as he lit the lamp and stood over me in its yellow glow.

“Get dressed, Nathan,” he said. “A schooner’s run aground.”

Beside me in bed, Grandpa grunted, rolled over, and pulled the blankets off me.

“I guess that means he’s not coming,” I said sitting up.

“Let the old man sleep,” Daddy said.

I was already dressed. The storm had chilled the cabin too much for me to get undressed the evening before. I pulled on the heavy slicker and rain hat Mr. Etheridge had given me when the surfmen got new ones in the autumn. I was surprised when we stepped outside to find the rain easing up and the stars peeking out between the clouds.

Daddy suggested the privy. No sense pissing in the bushes when a gust of wind could blow the wrong way and make a mess of things. I ran ahead of Daddy, and the wet sand about froze my bare feet.

“They’ll need help with the beach cart,” I called over my shoulder.

Daddy’s voice was swallowed in the wind, but he probably said that he’s catch up.

In the dark up ahead, I could see the Coston flare, the signal from the Pesa Island surfmen to the stranded ship that help was on its way. Offshore, to the north, was the faint glow of a lantern–from the troubled ship, no doubt.

The men from the Pea Island station–all seven of them–were already pulling the beach cart toward the wreck. Its wooden wheels creaked as it rolled through the deep sand, and its contents–the Lyle gun, the faking box filled with rope, the shovels, pickax, sand anchor, and breeches buoy–all jostled and rattled in the big open wagon. I grabbed hold of a haul rope and my muscles to theirs.

“Will you look at what the cat dragged in, “said Mr. Bowser between panting breaths. Benjamin Bowser was the number-one surfman-first in rank after Mr. Etheridge, the keeper. He was tall and lanky, with hallowed-out cheeks and a bushy black mustache.

I grinned at Mr. Bowser. “Can I light the fuse for the Lyle gun?” I asked, knowing no one would let me.

“You hush and just pull”, said Mr. Meekins sharply. Theodore Meekins was the widest of the crew, with hands like baseball mitts and serious, dark eyes. My face went hot when he reprimanded me. He was right. With a crew of men, and maybe even the captain’s wife and children clinging to the grounded ship, I had no business jabbering like a fool. I tipped my head down and pulled with all my strength. Daddy joined us on the other side of the cart.

Over our heads, the clouds parted and stars glittered. To our right, the ocean thundered, inky black except for the white strips of the breakers and a dancing streak of light where the moon caught the waves. The stiff west wind whistled in my ears and turned my cheeks and hands icy cold.

When we reached the wreck, I could see the outline of a three-masted schooner. She was maybe two hundred yards from shore, lying on her side with her sails torn away. She tossed with each wave as if she was trying to free herself from the shoal but couldn’t. On her slanting deck, I counted seven dark forms-the stranded sailors waiting for our help.

“Halt,” Keeper Etheridge commanded. Then, in a loud, firm voice, “Action!”

The Pea Island crew moved like well-trained soldiers, and Daddy and I stood out of their way. Stanley Wise, William Irving, and Lewis Wescott grabbed the shovels and pick and began to dig a hole to bury the sand anchor. George Midgett and L.W. Tillett unloaded the tall wooden crotch. It would be set up between the sand anchor and the wreck to hold the ropes above the surf. Richard Etheridge and Benjamin Bowser unloaded the Lyle gun, set it to aim at the ship, and got the flare ready to light the fuse on the gun.

The Lyle gun was ready to fire a weight and shot line over the wreck so the sailors could haul in the hawser line and fasten it to a mast. Then the breeches buoy-a pair of cutoff canvas breeches attached to a doughnut-shaped buoy-would be hauled out to the ship with a whip line and pulley, and one by one the sailors would be brought ashore, sitting in the breeches with the buoy holding them safely above the pounding sea.

Right when I expected to hear Richard Etheridge call “Ready” so we could hold our ears against the blast of the Lyle gun, instead I heard “Stop.” We all stood still and looked out toward the wreck. The lantern was flashing-the long and short flashes of Morse code. I knew the code’s letters, so I watched and read, “….i — t — e — w — a — i-t

u—n—t—i — l — d—a—y — l — i — t — e — w — a — i — t ….” Wait. Wait until daylight.

I gazed out at the wounded ship. Mr. Meekins had told me that not one in a hundred sailors knows how to swim. They must be terrified, I thought, of the black, boiling sea at night.

Mr. Bowser let out a grunt of disapproval. “That schooner starts breaking up, they won’t be hollering ‘wait’ anymore,” he said.

Mr. Etheridge crossed his arms over his chest and frowned. The waves, taller than a man, rumbled in one at time, each a powerful battering ram against the ship’s hull. It was up to Mr. Etheridge to decide what was best to do. He stroked his white beard with work-worn fingers and squinted out at the ship. Finally, he sighed. “Get the surfboat ,” he ordered. “If the surf dies down, we’ll use it instead of the breeches buoy.”

Half the crew stayed with Keeper Etheridge to keep a watch on the ship, and Daddy and I followed the other three crew members back toward the station. A we walked, we heard shouts behind us. The seven crewmen from the Oregon Inlet station trotted to catch up.

“What did you do, lie abed for another two hours before you decided to come help?” Mr. Bowser chided.

“Your Pea Island crew has got to learn how to use the telephone right,” said one of the Oregon Inlet crewmen. “I heard you wake up three other stations before you finally sounded our ring. We’re

two short and one long….”

I wasn’t sure which one of the Oregon Inlet crewmen was speaking. I’d only met them once before-their station was about five miles up the beach, and they were all white men and hard to tell apart in the dark. Just to make things more confusing, they had most

of the same names as the Pea Island crew: Grandpa says they have the same surnames because back before the war the granddaddies and great-granddaddies of the Oregon Inlet

crew used to

own the granddaddies and the great-grandaddies of the Pea Island crew, and they shared their family names with their slaves.

We got to the station, and two men pulled open the huge double doors so we would guide the surfboat, on its wheels, down the ramp to the beach. It was like a large rowboat, big enough for the whole crew of seven to row it and fit three or four sailors in to carry them back to shore. Mr. Meekins came out from the stables with one of the government team-the one who wasn’t lame. Once she was hitched to the surfboat, we all took hold of the drag ropes and pulled like mules ourselves. Even with all those men, one mule, and one strong, but skinny, twelve-year-old pulling on the drag ropes, it still felt like we were trying to lug an entire steamer through a sea of molasses. By the time we rejoined the rest of the crew, sweat ran down my back and arms. My heart was pounding hard, too. Soon the rescue would begin.

The wind had shifted from west to northwest. The three-masted schooner looked like a cow struggling to birth a calf, lying on her side, rocking in the surf.

“She breaking up yet?’ asked Mr. Browser.

The sky had brightened, and I noticed a soft pink glow on the horizon. Daylight. Wait until daylight.

Richard Etheridge shouted, “Unload!” The Pea Island crew went into action with the surfboat, each man with his own job, unhitching the mule, pushing the surfboat to the edge of the sea, casting off the side lashings, taking off the wheels, lowering the boat onto the sand.

Within seconds, amid shouting of the commands “Take life preservers!” “Take oars!” and “

Go!” the men had run the boat out into the breakers and jumped in. I held my breath as a huge wave crashed over the bow.

“Give way together!” Keeper Etheridge called. The oars moved in unison. Mr. Etheridge gripped the long steering oar. The surfboat faced the breakers head on and sliced through them. It moved swiftly over each towering wave toward the dark silhouette of the schooner.

The Oregon Inlet crew waited with Daddy and me. We watched as the surfboat reached the wreck.

In the eddy of calmer water on the lee side of the schooner, the surfmen were able

to pull up close. A ladder had already been lowered, and the first of the sailors climbed down and reached out to be helped into the boat.

The sky turned light blue, and the pink glow spread until a speck of sun peeked up.

“Damn, if they’re not loading their baggage as well!” Daddy said under his breath.

Four sailors had climbed safely into the surfboat, and a large crate was being lowered from the schooner’s deck.

I frowned. Didn’t they know these men were risking their lives to save them?

With the surfboat sitting low under its heavy load, the crew rowed back toward the shore. The three remaining sailors watched, waiting for a second run.

Near shore, the surfboat got turned almost sideways. I yelped as a tall wave broke over its side and the men had to throw weight to keep from capsizing. Daddy and I ran to the water and with the Oregon Inlet crew, grabbed the sides of the boat and dragged it up onshore.

The sailors jumped out and scrambled up onto dry land as we unloaded the crate.

Suddenly there was a tremendous crack, loud as a gunshot.

“She’s breaking up!” someone yelled.

“Take oars!” Mr. Etheridge shouted . “Go!”

We shoved the surfboat back into the sea, and it crashed through the breakers, the men pulling hard at the oars. The sea would be rushing into the belly of the schooner now. Soon she would be in pieces. The captain and two sailors waved frantically. No one would be thinking of loading baggage now.

Another crack sounded, and the schooner lurched.

I watched the mast, willing it to stay intact until the men were safely out of its reach.

The sailors looked panicky. Two of them already clung to the ladder. As the surfboat approached them, one sailor tried to leap in too soon, missed and had to be hauled in over side, his legs flailing like a scared chicken. The other sailor, and finally the captain, always last, were loaded in , and the crew rowed furiously away from the wreck. Only when they were a safe distance away did I dare to take my eyes off the mast.

“You, boy, do you know where the teapot is at the station?” It took me a moment to realize one of the Oregon Inlet surfmen was talking to me.

“Yes, sir,” I said.

“Let’s go, then.”

There was a creaking and a crash. When I turned to look at the wreck again, the mast had fallen.

I followed the surfman, and the four sailors followed us in tired silence.

At the station, I stoked the fire and pumped water for tea.

“I’m Mr. Forbes,” said the surfman as he put six mugs and the steaming teapot on the table in front of the sailors. “And you are?”

We looked at them expectantly, and they looked at us.

All four of them had hair the color of sea oats-so blond it was almost white-and three of them had faces and hands as red as fish blood. I wondered if they were that color all over, or if it was just from the cold. They said nothing.

“Are you not from the States, then?” Mr. Forbes asked our guests.

They sipped their tea, folding their cold hands around the warm mugs. “Dank-ew,” they each said, nodding.

Mr. Forbes signed. I watched to see if the redness would go away as they warmed up.

So these were the Europeans Mr. Bowser had told me about-men from Poland, Sweden, Norway, and other countries from across the Atlantic who signed on as crewmen on American ships. They were white men but, Mr. Bowser said, had never been taught to treat a black man as less than a man. I smiled at them, and they smiled

back.

There was the sound of approaching voices.

“I’d never have had you take the baggage if I’d known we were that close to breaking up,” said a man with a Yankee accent.

“We can’t thank you enough,” said another Yankee. “The

Emma C. Cotton will be a total loss, but you saved all men on board.”

The schooner-the

Emma C. Cotton-must have come from a port in a Northern

State.

I helped Mr. Forbes and Pea Island’s cook, Lewis Wescott, prepare a breakfast of bacon and biscuits for everyone. I carried the pot of hot coffee from the cookhouse to the main station house and stepped into the dining room. There, I stopped. The men were sitting around the table, helping themselves to the mounds of biscuits and thick slabs of

bacon. All of the men: the Oregon Inlet crew, the Pea Island crew, Daddy, and the sailors. White men and black men sitting at table together. It was just like Mr. Bowser had told me it would be after a rescue on Pea Island.

“You going to bring that coffee over here or just stand there and wait for it to get cold?” Mr. Bowser called to me.

I hurried to the table with the pot, and Daddy handed me a plate full of food.

That wasn’t the first time I felt it-the wanting to be a surfman-but I probably felt it then stronger than I ever had before. Stronger than when we lived on Roanoke Island and William, Floyd, and I did mock drills with an imaginary surfboat. Stronger than when Daddy, Grandpa, and I moved out here to Pea Island and I first watched the surfmen do their drills. Stronger than when Mr. Meekins said he’d teach me how to swim in the heavy surf.

On the way back to our cabin was the first time I said it to Daddy. Turns out I probably should have kept it to myself.

“Dammit, Nathan, you’ve got no appreciation for what I’m giving you.” He said. His round face had more lines in it than usual, and his shoulders, usually so square and strong, drooped a bit. “I’ve got us set up with our own boat and nets, working for ourselves. Would you rather work as a day laborer for pennies, the way most black folks have to?”

“No, I’d rather be a

surfman,” I said, knowing I should have bit my tongue and kept quiet, especially with Daddy so worn out.

We reached the cabin, and he yanked open the door and slammed it behind us.

“Nathan,” He fixed me with his dark eyes. “There’s a lot you don’t understand….

about the way things are. You won’t ever be a surfman. Now put it out of your mind.”

He sniffed, smoothed his bristly mustache, and plopped onto his cot. I stared at him, my fists clenched. But this time I kept my mouth shut.

“Now let me get some sleep,” he said, and turned his back to me.

Grandpa came in with an armload of brush for kindling and said he was going fishing since he was, apparently, the only one around here with sense enough to think

about getting something for supper.

I lay on my bed and closed my eyes but didn’t sleep. I was powerful angry at Daddy for telling me not to hope, and only wondering a little about those things he said I didn’t understand.

. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.